Bilham, R., V. K. Gaur and P. Molnar, Himalayan Seismic Hazard, Science, 293, 1442-4, 2001. Science Magazine Dowload.

PERSPECTIVE: EARTHQUAKES

Himalayan Seismic Hazard

Roger Bilham, Vinod K. Gaur, Peter Molnar

R. Bilham and P. Molnar are in the Department of Geological Sciences and the Cooperative Institute for Research in environmental Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA. E-mail: bilham@colorado.edu. V. K. Gaur is in the Indian Institute for Astrophysics, Bangalore 560 034, India.

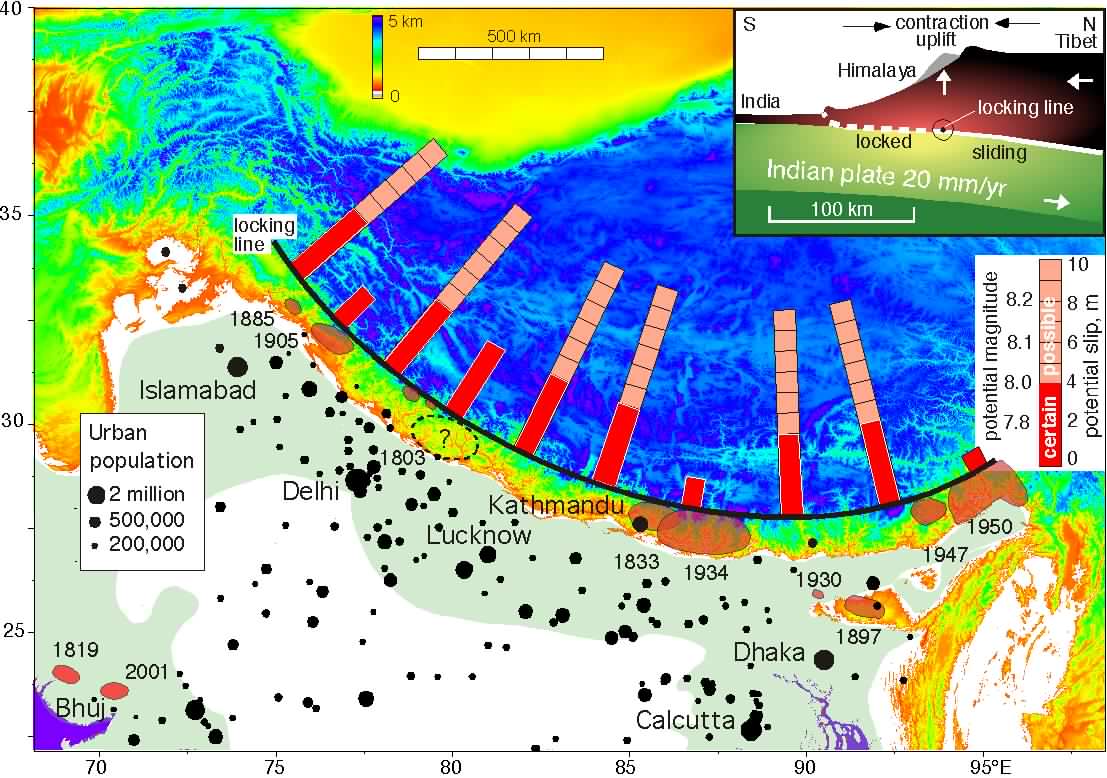

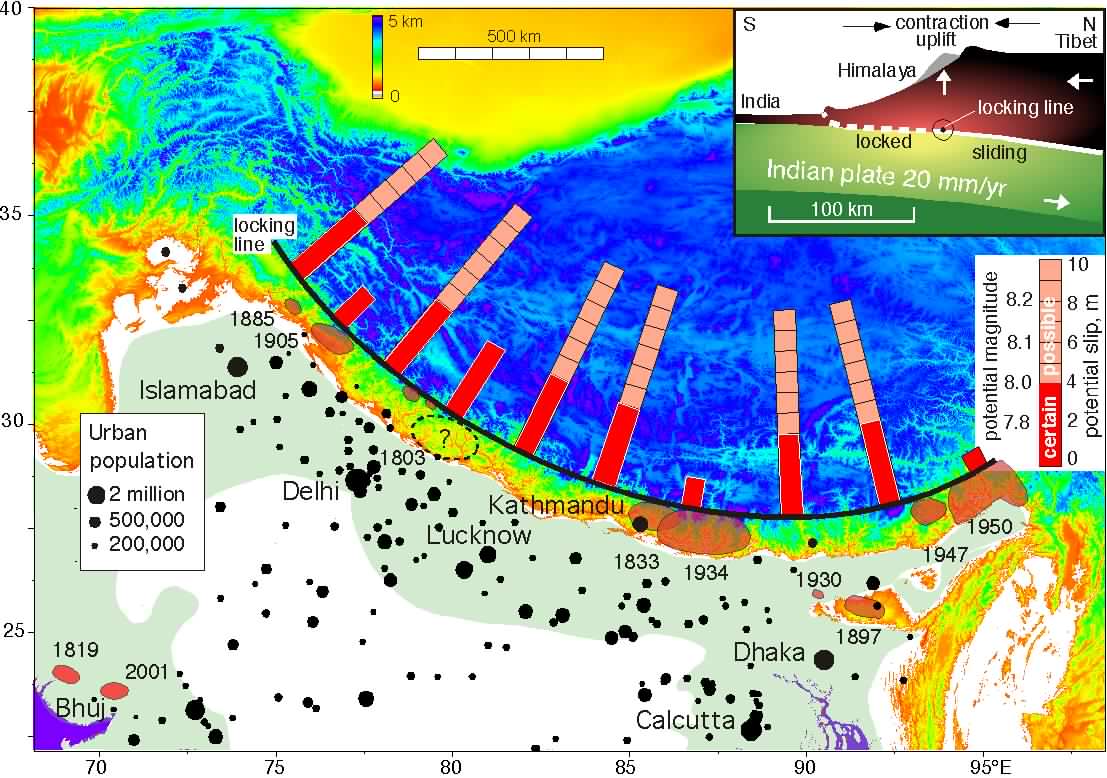

Five major earthquakes have visited India in the past decade (see the table), culminating in the devastating Bhuj earthquake of 26 January 2001. That earthquake in particular called attention to the hazards posed by buildings not designed to withstand major but obviously probable earthquakes. It also focused the eyes of the public away from a part of India where even worse damage and loss of life should be expected-the Himalayan arc (see the figure). Several lines of evidence show that one or more great earthquakes may be overdue in a large fraction of the Himalaya, threatening millions of people in that region.

A wealth of geophysical evidence demonstrates that south of the

Himalaya, the top surface of India's basement rock flexes and

slides beneath the Himalaya-not steadily but in lurches during

great earthquakes (see the inset in the first figure) (1,

2). This pattern resembles that found where lithospheric

plates beneath oceanic regions converge rapidly: that is at deep-sea

trenches, where the ocean floor flexes down seaward of the trench,

the entire oceanic lithosphere plunges deep into the Earth's mantle,

and great earthquakes occur most commonly. Extreme examples are

the great earthquakes in Chile in 1960 and in Alaska in 1964.

Only during such earthquakes does the entire plate boundary rupture.

Second, Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements show that

India and southern Tibet converge at 20 ± 3 mm/year (3).

A 50 km-wide region centered on the southern edge of the Tibetan

Plateau strains to absorb about 80% of this convergence. This

region also shows localized vertical movement (4), and small

earthquakes are most common here (5). The surrounding Himalaya

accommodates the remaining 20%. Two meters of potential slip in

earthquakes thus accumulate each century. In contrast, control

points in southern India and southernmost Nepal approach each

other no faster than a few mm/year (6). As the Bhuj earthquake

shows, this deformation, although slow, is far from negligible.

Third, in the Himalaya the potential slip accumulates almost entirely

as elastic rather than inelastic strain, which would permanently

deform the rock. Analyses of deformed river terraces in the foothills

of the Himalaya demonstrate an advance of 21 ± 3 mm/year

in southern Nepal (7) during the past ca. 10,000 years. The minor

difference between this rate, measured at the southern edge of

the Himalaya and applicable to durations spanning many great earthquakes,

and the 20 ± 3 mm/year measured with GPS implies that at

most a small fraction (<10%) of the strain could be inelastic.

Earthquakes must therefore release most, if not all, of India's

2 m/century convergence with southern Tibet.

Little is known about Himalayan earthquakes in the 18th century

and before. Great earthquakes in the Himalayan region occurred

in 1803, 1833, 1897, 1905, 1934 and 1950 (see the figure). The

1803 earthquake caused damage between Delhi and Lucknow. Recent

reëvaluations of the 1833 Nepal (8) and 1905 Kangra earthquakes

(9, 10) indicate that rupture lengths were less than 120 km, smaller

than previously believed (1, 11). An analysis of geodetic deformation

during the 1897 earthquake (12) confirms that it occurred 100

km south of the Himalaya and therefore did not relieve strain

in that belt. Thorough studies of the destruction, and thus the

intensity of shaking for the 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquake were

carried out in Nepal (13) and India (14). Together with geodetic

constraints (15), they imply that a 200 to 300 km long segment

of eastern Nepal ruptured (16). Similarly, locations of aftershocks

of the 1950 Assam earthquake imply a rupture zone ~200 km long,

with complexities at its eastern end (2, 17).

Although the major earthquakes that have occurred along the Himalaya

since 1800 differed in dimensions. there is no doubt that they

destroyed vast regions along the front of the Himalaya. More important

today, however, less than half of the Himalaya (see the figure)

has ruptured in that period.

Surface ruptures have not been found for any of these events.

There are thus no geological constraints of recent ruptures, and

geologists are concerned that paleoseismic investigations across

Himalayan surface faults may yield misleadingly long recurrence

intervals. Moreover, repeat surveys of trigonometrical points

installed before the 1905, 1934, and 1950 earthquakes have yet

to be made with modern techniques. The amplitudes of long-period

seismic waves have provided quantitative measures of the seismic

moments (a measure of earthquake size) of the 1934 and 1950 earthquakes

(17). Knowledge of the lengths of the ruptures and sensible estimates

of the width from various sources yield ~4 m of slip in 1934 and

~8 m of slip in 1950 (18). Uncertainties in these estimates permit

slip as small as 2 m in 1934 and as high as 16 m for 1950, but

such amounts would be unusual for earthquakes of their magnitude.

These less direct measurements thus imply an average slip of ~4

m during great earthquakes.

Despite the diverse quality of data in the past two centuries,

we can be sure that we are not missing any great event since 1800.

This permits us to estimate the minimum slip potential that has

accumulated along the Himalaya since the last grreat earthquake

(see the figure). We divide the central Himalaya into 10 regions,

with lengths roughly corresponding to those of great Himalayan

ruptures (~220 km). With a convergence rate of 20mm/year along

the arc, six of these regions currently have a slip potential

of at least 4 m-equivalent to the slip inferred for the 1934 earthquake.

This implies that each of these regions now stores the strain

necessary for such an earthquake. Moreover, the historic record

(19-21) records no great earthquake throughout most of the Himalaya

since 1700, suggesting that the slip potential may exceed 6 m

in some places.

Given that geological investigations of the 1905 and 1934 ruptures

did not reveal surface ruptures but that river terraces have been

warped and the foothills have grown during prehistoric great earthquakes,

we cannot rule out the possibility that parts of the Himalaya

have not ruptured in major earthquakes for 500 to 700 years and

will be associated with slip exceeding 10 m. The mid-Himalayan

20th century earthquakes would then have been atypically small.

The weakest link in the arguments above is the uncertainty in

the amount of slip during great earthquakes. Yet, because the

longer the time since the previous earthquake, the larger the

potential slip will be to drive the next one, if the fraction

of the Himalaya due for a major earthquakes is smaller than the

55% we assign it, the more severe those less frequent great earthquakes

will be. Even if only one segment has stored potential slip comparable

to that of the 1950 Assam earthquake, the largest intracontinental

earthquake in recorded history (18), a replication of that earthquake

along the more populous segments of the Himalaya would be devastating.

The population of India has doubled since the last great Himalayan

earthquake in 1950. The urban population in the Ganges Plain has

increased by a factor of ten since the 1905 earthquake, when collapsing

buildings killed 19,500 people (9). Today, about 50 million people

are at risk from great Himalayan earthquakes, many of them in

towns and villages in the Ganges plain. The capital cities of

Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Pakistan and several other

cities with more than a million inhabitants are vulnerable to

damage from some of these future earthquakes.

The enforcement of building codes in India and Pakistan mitigates

the hazards to this large population, but a comparison between

fatalities in the 1819 Katchch and 2001 Bhuj earthquakes is not

encouraging. The population of Kachch has increased by a factor

of ten. Two thousand fatalites occurred in 1819 (22), compared

to the 18,000 confirmed and possibly 30,000 unconfirmed fatalities

this year. The implemented seismic code apparently did not lessen

the percentage of the population killed. Like the Himalayan earthquakes,

the Bhuj event occurred in an identified zone of heightened seismic

hazard. Projecting these figures to just one of the possibly several

overdue Himalayan earthquakes (for example a repeat of the Kangra

1905 event) yields 200,000 predictable fatalities. Similar conclusions

have been reached by Arya (23). Such an estimate may be too low

by an order of magnitude should a great earthquake occur near

one of the megacities in the Ganges Plain.

Danger zone. This view of the Indo-Asian collision zone

shows the estimated slip potential along the Himalaya and urban

populations south of the Himalaya (U.N. sources). Shaded areas

with dates next to them surround epicenters and zones of rupture

of major earthquakes in the Himalaya and the Kachchh region, where

the 2001 Bhuj earthquake occurred. Red segments along the bars

show the slip potential on a scale of 1 to 10 meters, that is,

the potential slip that has accumulated since the last recorded

great earthquake, or since 1800. The pink portions show possible

additional slip permitted by ignorance of the preceding historic

record. Great earthquakes may have occurred in the Kashmir region

in the mid 16th century (21) and in Nepal in the 13th century

(8). The bars are not intended to indicate the locus of specific

future great earthquakes, but are simply spaced at equal 220-km

intervals, the approximate rupture length of the 1934 and 1950

earthquakes. Black circles show population centers in the region;

in the Ganges Plain, the region extending ~300 km south and southeast

of the Himalaya, the urban population alone exceeds 40 million.

(inset) This simplified cross section through the Himalaya indicates

the transition between the locked, shallow portions of the fault

that rupture in great earthquakes, and the deeper zone where India

slides beneath Southern Tibet without earthquakes. Between them,

vertical movement, horizontal contraction, and microearthquake

seismicity are currently concentrated (3-5).

References

1. L. Seeber, J. Armbruster, in Earthquake Prediction:

An International Review, Maurice Ewing Series 4, D. W. Simpson,

P. G. Richards, Eds. (Amer. Geophys. Un., Washington, DC, 1981),

pp. 259-277.

2. P. Molnar, J. Himalayan Geology 1, 131

(1990).

3. K. Larson, R. Bürgmann, R. Bilham, J. Freymueller, J.

Geophys. Res. 104, 1177, (1999).

4. M. Jackson, R. Bilham, J. Geophys. Res. 99,

13897 (1994).

5. M. Pandey et al., Geophys. Res. Lett., 22,

751 (1995).

6. J. Paul et al., Geophys. Res. Lett. 28,

647 (2001).

7. J. Lavé, J.-Ph. Avouac, J. Geophys. Res. 105,

5735 (2000 )

8. R. Bilham, Current Science 69, 155 (1995).

9. N. Ambraseys, R. Bilham, Current Science 79,

101 (2000).

10. R. Bilham, Geophys. J. Int. 144, 1 (2001).

11. C. S. Middlemiss, The Kangra Earthquake of 4th April, 1905,

Mem. Geol. Surv. India, Vol. 37 (Geol. Surv. India, Calcutta,

1910; reprinted 1981).

12. R. Bilham, P. England, Nature 410, 806, (2001).

13. Rana, Maj. Gen. Brahma Sumsher J. B., Nepalko Maha Bhukampa

(The Great Earthquake of Nepal), published by the author in

Kathmandu, Second ed. 1935.

14. J. A. Dunn, J. B. Auden, A. M. N. Ghosh, D. N. Wadia,

The Bihar Earthquake of 1934, Geol. Surv. India Mem.

73, 1939.

15. R. Bilham, F. Blume, R. Bendick, V. K. Gaur, Current Science

74, 213 (1998).

16. M. R. Pandey, P. Molnar, J. Geol. Soc. Nepal 5,

22 (1988).

17. W.-P. Chen, P. Molnar, J. Geophys. Res. 82,

2945 (1977).

18. P. Molnar, Deng Q., J. Geophys. Res. 89,

6203 (1984).

19. A. Bapat, R. C. Kulkarni, S. K. Guha, Catalog of Earthquakes

in India and Neighborhood from historical period up to 1979

(Ind. Soc. Earthq. Tech, Roorkee, 1983), 211 pp.

20. K. N. Khattri, Tectonophysics 138, 79 (1987).

21. R. N. Iyengar, S. D. Sharma, Earthquake History of India

in Medieval Times (Central Building Research Institute, Roorkee,

1998), 124 pp.

22. R. Bilham, in Coastal Tectonics, I. S. Stewart, C.

Vita-Finzi, Eds. (Geol. Soc. London, London, 1999), pp. 295-318.

23. A. S. Arya, Current Science 62, 251 (1992).

Table 1 Fatalities from earthquakes in India, and estimates

of rupture parameters of Himalayan earthquakes

Rupture zones entered in italics are constrained by seismic

or geodetic data. The range of uncertainty in rupture parameters

is indicated by a minimum and maximum slip estimate.

magnitude fatalities length width slip (m) ref.

date latitude longitude Ms km km min. max.

1720 Jul 15 29 77.5 Delhi ? ? 27

1819 Jun 16 23.6 68.6 Kachchh 7.7±0.2 2000 120 15 9

12 28

1737 Sep 30 not an earthquake Calcutta - <3000 29

1803 Sept 1 30 78 Kumaon 8? ? 120 60 2 6 27

1833 Aug 26 28 88.5 Kathmandu 7.7±0.2 500 120 70 2 3

9

1869 Jan 10 25 93 Cachar 7.5 2 15

1885 May 30 34.1 74.6 Sopor, Kashmir 7 3000 30 20 1 2 26

1897 Jun 12 26 91 Shillong 8.1±0.1 1542 110 35 10 20

14

1905 Apr 04 32.3 76.3 Kangra 7.8±0.2 19500 120 60 2

5 11

1918 Jul 08 24.5 91 Srimigal,Bengal 7.6 ? 26

1930 Jul 02 25.8 90.2 Dhubri, Assam 7.1 0 26

1934Jan 15 26.6 86.8 Bihar/Nepal 8.2±0.1 10500 220 80

3 5 22

1943 Oct 23 26.8 93 Assam 7.2 ? 26

1947 Jul 29 28.63 93.73 Assam 7.7 ? 100 50 2 4 22

1950 Aug15 28.5 96.7 ArunchalPradesh 8.5 1542 200 90 6 20

32

1956 Jul21 23.3 70 Anjar 7 113 36

1967 Dec10 17.37 73.75 Koyna 6.5 177 36

1970 Mar 23 21.7 73 Broach 5.4 30 36

1975 Jan 19 32.38 78.49 Kinnaur 6.2 60 36

1988 Aug 06 25.13 95.15 Manipur 6.6 35 36

1988 Aug 21 26.72 86.63 Udaypur 6.4 6500 36

1991 Oct 20 30.75 78.86 Uttarkashi 6.6 769 36

1993 Sep 30 18.07 76.62 Latur 6.3 7610 36

1997 May 22 23.08 80.06 Jabalpur 6 39 36

1999 Mar 29 30.41 79.42 Chamoli 6.8 103 36

2001 Jan 26 23.4 70.3 Bhuj 7.6 >20000 36