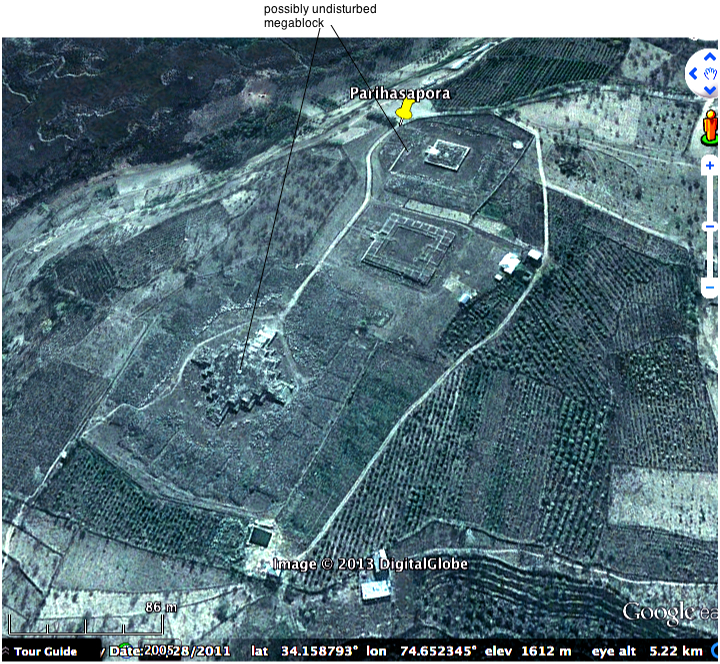

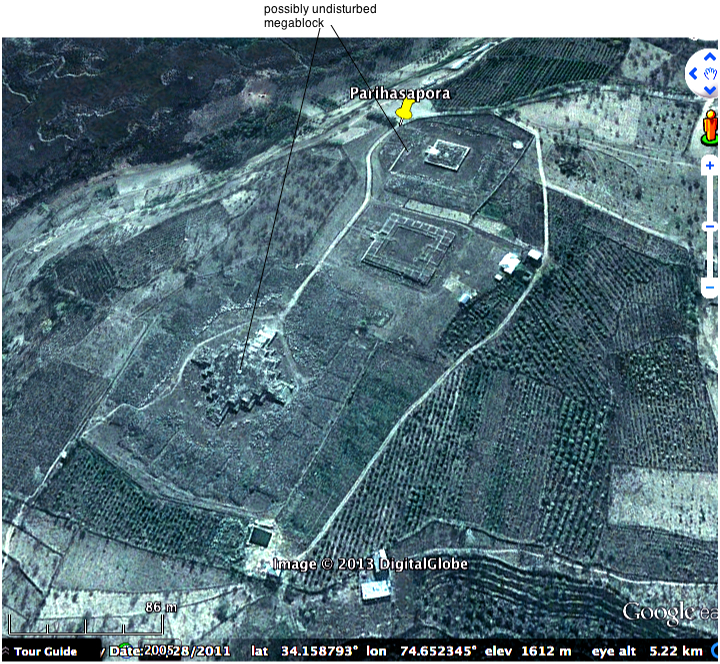

This complex is part of an ancient city founded on an isolated table-land of Karewa sediments east of Patan, and north of the Srinagar/Patan road. Its surviving dimensions are about 100 m x 500 m. Several other Buddhist remains are to be found nearby on the table-land that are detailed at length by Aurel Stein (pdf map). It is possible that the site was an island during the time of its early construction, surrounded by a lake caused by a blocakge of the Jhelum below Baramula (Bilham and Bali, 2013). The lake would have facilitated the transport of temple monoliths from distant limestone quarries.

The site consists of three or more large structures of which only the base plinths have survived. These have been cleared, partly reassembled and, in places, repaired, although the structures that once topped the plinths no longer exist. Unused re-assembly materials lie in heaps to the side of the structures. The bulk of these excess materials are cobble and boulder-sized undressed rubble-fill used to core the inner surfaces of the dressed-stone stuctures. Aurel Stein identified numerous locations on the tableland and in the valley see pdf.

The largest disturbed stone block that presently survives 2m x 2m x 1.5m is found on the westernmost plinth. This appears to be a floor base rather than a roof capstone. A massive undisturbed stone block, also a foundation stone, lies at the center of the easternmost plinth. Kak remarks "The floor of the chaitya at Parihasapura consists of a single block approximately 14 x 12 x 6 feet."

One of the largest blocks on the easternmost ruin at Parihansapura being inspected By Dr. B. S. Bali. This block, unlike surrounding construction materials, was not scavenged presumably due to its immense weight. A number of Parihasapora monliths have been incorporated into the Sugandhesa Temple.

Chak on the Bhuddist monastery at Parihasapura. "Of the monasteries there is little to be said, as only one example survives - namely, the Rajavihara of Parihasapura. In plan it is a cellular quadrangle facing a rcctangular courtyard. The cells were preceded by an open verandah. In the middle of one side was the flight of steps which afforded an entrance and exit. The central cell on this side served as the vestibule. In the range of cells on the opposite side are a set of more spacious rooms which served either as a refectory or as the abbot's private apartments. Externally, and probably internally also, the walls were plain. The roof was probably sloping, and gabled like modern roofs in Kashmir.

Parihasapura has also bequeathed to us the only surviving example of a Buddhist chaitya, or temple. It is a square chamber built upon a square base similar to that of the stupa, save for the offsets and three stairs, and is enclosed by a plain wall, with entrance facing the temple stairs. The stairs lead up to the portico which gave admission to the sanctum. The latter was an open chamber surrounded on all sides by a narrow corridor which served as a circumambulatory path. At the four corners of the sanctum are bases of pillars which no doubt held some sort of screen designed partly to conceal the Holy of Holies from profane eyes. As the external wall of the corridor has been almost razed to the ground, it is very difficult to say whether there were openings in it for admission of light and air; probably there were.