CHARLES STEWART MIDDLEMISS 1859-1945

Middlemiss graduated from Cambridge in 1880, a year after Tom La Touche, and 7 years before Philip Lake all of whom joined the Survey of India. Their Professor at Cambridge was Thomas McKenney Hughes.

The following is a 1945 obituary by L. L. FERMOR [Obituary

Notices of the Royal Society, 14(5), 63-Nov 1945] with annotations and links to

additional materials. All headings and comments in blue below are not in Fermor's account. Click here for Bibliography.

With the death of Charles Stewart Middlemiss on 11 June

1945, Indian geology has lost its doyen, a man of great versatility who lived

an active life up to within some two months of his death in hospital in

Tunbridge Wells. Middlemiss was the son of Robert Middlemiss of Hull and

Elizabeth Findleyson Gale and was born in Hull on 22 November 1859. He was

educated at Caistor and St. John's College, Cambridge, the college from which

so many good geologists have come. He took his B.A. degree in 1881 and joined the

Geological Survey of India as Assistant Superintendent on 21 September 1883,

when H. B. Medlicott was still head (then known as Superintendent) of the

Department. As Medlicott joined the Department in 1854, but three years after

its foundation by Dr. Thomas Oldham in 1851, anyone who knew Middlemiss could

in conversation go back in anecdote almost to the Department's foundation. With

the death of Middlemiss the doyen of Indian geology is now Mr. Philip Lake who

served for a short period from 1887 to 1891, followed closely by Sir Thomas

Holland, who joined the Geological Survey of India in 1890.

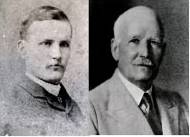

The photo on the left was taken when Middlemiss joined the

Geological Survey of India in 1882 (Courtesy of the Director Geological Survey

of India), and the one on the right from c. 1930 is from a photograph provided

by his daughter for Middlemiss's extended FRS obituary (written by Fermor).

During his service Middlemiss

did field work in the Himalaya, the Salt Range and Hazara; in Coimbatore, Salem

and the Vizagapatam Hill Tracts in the Madras Presidency; in the Shan States

and Karenni in Burma; in Bombay, Central India and Rajputana, and finally in

Kashmir. During spells at Headquarters he was Curator of the Geological Museum

in 1898-1899, and in charge of the Headquarters Office during 1907-1908. He was

promoted Deputy Superintendent in 1889, and Superintendent in 1895. He

officiated as Director of the Department for two periods, in 1914-1915 and in

1916. He paid a visit on deputation to Ceylon in 1903.

According to normal

custom Middlemiss should have retired from the Geological Survey of India on

reaching the age of 55 in 1914; but on account of the war and the difficulty of

then obtaining recruits his service was extended, so that he did not leave the

Department until 1 April 1917, after being decorated with the C.I.E. in 1916.

As a result of this Middlemiss ranks second for long service in the Geological

Survey of India, over thirty-three and a half years, the record being held by

William King with a total service of over thirty-seven years (due to his

retention in the Department until the age of sixty). Middlemiss then went

direct from the Geological Survey of India to the service of His Highness the

Maharaja of Kashmir and Jammu , with the title of Superintendent, Mineral

Survey of Jammu and Kashmir State. He did not retire from Kashmir service until

his seventy-first year, when, in the recess period of 1930, and after a total

service in India of over forty-six years, he gave much pleasure to those

geologists who had not met him by returning to Calcutta to collect a few

personal possessions and say farewell to the focus of so much active life.

HONOURS Of other

scientific activities we may record that Middlemiss became an ordinary and life

member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1884, and a Fellow in 1912. At the

time of his death he was by four years the senior member of the Society (now

with the appellation 'Royal'), and also the senior Fellow. He became a Fellow of the Geological

Society in 1900 and was awarded the Lyell Medal in 1914. He was elected a

Fellow of the Royal Society in 1921. He was President of the Geological Section

of the Fourth Indian Science Bangalore in 1917. He was President of the Ninth

Indian Science Madras in 1922, and of the Mining and Geological Institute of

India in 1928. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in 1934 and of

the American Geographical Society of New York in 1936.

MARRIED LIFE AND CHILDREN

In 1886 Middlemiss married Martha Frances Wheeler, daughter of the late General

F. Wheeler, Bengal Staff Corps. They had five sons and one daughter. Two sons

died young in India, two were killed in the last war, one in Gallipoli and one

in France, and the fifth, Hugh Percival, is pursuing a musical career. On

retiring from India Middlemiss settled down at Crowborough Sussex, where he

became a centre of local activities. Mrs Middlemiss died in July 1931. To his

daughter, Mrs. Forward, who has kept his house for him during this war, I am

indebted for help in preparing this notice, and for his photograph.

CHARACTER Before

discussing Middlemiss's work it will be pleasant to give some account of his

personal characteristics. As I and my contemporaries first knew him was already

in the forties-partially bald with an aureole of grey hair, bright blue eyes,

pleasant friendly expression, very sturdily built and above medium height. He

had an extraordinarily youthful mind, was always ready for fun, and was often

the life and soul of parties, especially if youngsters were present. Women

liked him for his courtesy and chivalry.

Middlemiss had an experimental mind and was

willing to try anything and especially anything new. The result was that he had

a multitude of interests outside geology, the principal of which were sketching

and music, as recorded in Who's Who. But he was also interested in verse, in

Esperanto, in chess, and in rowing and in lawn tennis, which he was playing in

local tournaments until he was eighty.

ART Of these

interests the most important was sketching in water colour. From India he

recorded in this medium the incidents of camp life and travel and the scenery

amidst which he worked. Some of these sketches are very amusing and some very

charming. Fortunately he was induced recently to arrange these skethes and to

list of these sketches chronologically in a portfolio, which is now in the

possesion of his daughter. Amongst his effects there were also some framed

sketches and one of them will, it

is hoped, be reproduced in a forthcoming issues of Notes and Records [This appeared in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 4, No. 2. (Oct., 1946), pp. 214-215]. It is a view of the Chor Mountain, clearly visible from

Simla, and done in 1884. According to the old standing orders of the Geological

Survey of India, officers of the Department were required to illustrate their

reports with drawings and sketches, and only if they were so incompetent as to

be unable to do this were they, as a concession, allowed to use photography! As

a result, in my day, all officers of the Department were provided with a camera

lucida as a part of their camp equipment to enable them to sketch accurately

the outlines of hills and mountain scenes. Several of the earlier officers used

this aid with great effect, e.g.Thomas Oldham, Griesbach, and, facile princeps, Middlemiss.

ART Of these

interests the most important was sketching in water colour. From India he

recorded in this medium the incidents of camp life and travel and the scenery

amidst which he worked. Some of these sketches are very amusing and some very

charming. Fortunately he was induced recently to arrange these skethes and to

list of these sketches chronologically in a portfolio, which is now in the

possesion of his daughter. Amongst his effects there were also some framed

sketches and one of them will, it

is hoped, be reproduced in a forthcoming issues of Notes and Records [This appeared in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 4, No. 2. (Oct., 1946), pp. 214-215]. It is a view of the Chor Mountain, clearly visible from

Simla, and done in 1884. According to the old standing orders of the Geological

Survey of India, officers of the Department were required to illustrate their

reports with drawings and sketches, and only if they were so incompetent as to

be unable to do this were they, as a concession, allowed to use photography! As

a result, in my day, all officers of the Department were provided with a camera

lucida as a part of their camp equipment to enable them to sketch accurately

the outlines of hills and mountain scenes. Several of the earlier officers used

this aid with great effect, e.g.Thomas Oldham, Griesbach, and, facile princeps, Middlemiss.

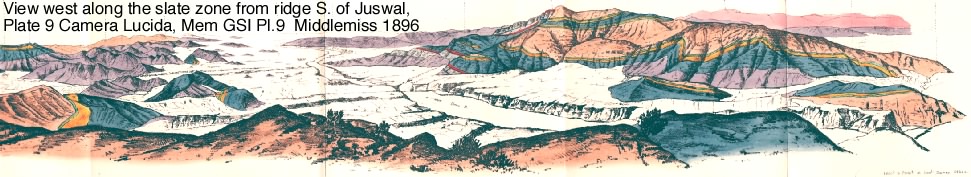

A magnificent example of what can be

done by a man of combined artistic and scientific temperament is Middlemiss's

own memoir on the Geology of Hazara and the Black Mountain (Mem. Geol. Surv.

India, 26, 1896). Amongst the numerous

illustrations are some panoramic views of which the outlines were drawn with

the aid of a camera lucida; to the panorama the geological formations have been

added using the same colours as in the geological map illustrating the memoir.

Plate 9, to choose one of several, is a superb example of the way in which

geological reports can be illustrated so as to give results far more effective

and explanatory of the scenery than are obtainable by photography. Apart

from the multitude of the usual geological sections and other illustrations that

this memoir contains, all drawn of course by the author, we may mention

specially two plates of micro-sections of rocks hand-drawn by Middlemiss and

much clearer in elucidating the composition and structure of the rocks depicted

than the majority of micro-photo graphs that are published. In this last

respect Middlemiss agreed with Harker, who also preferred to draw his own

micro-pictures of rock sections.

MUSIC Concerning

Middlemiss's second hobby, music, we must note that he comes of a musical family.

So it is not surprising that with his experimental mind, he should have looked

at music experimentally. Not being myself a musician it is suitable that I

should quote here a passage from a letter from Sir Edwin Pascoe that explains

clearly this experimental outlook:

He thought he was fond of music and so

he was in a way. But it was not so much music itself which attracted him but

the various instruments which produced it, the method of scoring it, and any

stage device for illustrating it. If Middlemiss were present at a performance

of Wagner's opera Die Walkre. I can imagine him consumed with curiosity as to

how the Valkyries on their horses were made to gallop over the clouds. While

all true lovers of drama and music would be doing their best to forget that the

figures in the stage sky were just dummies mechanically propelled with ropes

and pulleys, and trying to imagine that they were real horses and horsewomen

carrying the dead bodies of heroes to Valhalla. Middlemiss would probably been

endeavouring to invent some more realistic method of depicting the scene.

It is not surprising

that Middlemiss invented a new musical notation (see Bibliography, 1935). The

fundamental reason for this appears to have been his objection to the fact that

in the usual notation the same note may be indicated in more than one way: e.g.

that C sharp and D flat are rendered by striking the same key. On this notation

Pascoe writes to me: His musical notation was

not without merit, and he took it quite seriously. I think it failed chiefly in

that you had to read and identify every note. In our ordinary system this is

not necessary. In a rapid rise up or down the scale, for example, you do not

read every note-you have not time-but are conscious of a regular sequence. What

you have to look out for, in fact, is any irregularity or interruption in the

sequence.

VERSE & ESPERANTO

Middlemiss also amused himself with verse, and especially by experimenting

with various forms of verse. Whilst his results could not be described as

poetry they were very tolerable and readable verse. He liked especially lyrical

ingenuities such as rondeaux, rondels, ballades, triolets, etc. Middlemiss in

his enthusiasm for new methods was an active exponent of Esperanto in its early

days and acted as Honorary Secretary of the Calcutta Esperanto Society (or was

it the Esperanto Society of India?) for some years. He tried to infect the

Geological Survey of India with this new language and several of us allowed

ourselves to be dragged at his chariot wheels. For some years, in the days when

we had our lunch sent to office, Middlemiss, Vredenburg and I used to lunch

together, and invariably our greetings and conversation opened in Esperanto

before reverting to English. On my

first period of leave, in 1908, I visited Geneva, immediately after an

International Esperanto Congress had been held there. I tried in vain to make

use of the new language, and was forced to use my inferior French. On my return

to India I reported the results to Middlemiss and Vredenburg and cut myself

adrift from Esperanto. But Middlemiss carried on for some years. I have heard

of one example of Esperanto proving useful. Hayden (later Sir Henry Hayden)

when on duty in Afghanistan used it in writing to headquarters in Calcutta, for

his letters if opened en route would be understood by no one!

The difficulty that faces inventors of new languages like Esperanto, or

even Basic English, or new systems of musical notation like Middlemiss's, is

that even if that new language or system is better than the old, it stands no

chance of replacing existing languages or systems. For by learning the new you

cannot thereby avoid also learning the old, for the simple reasons that all

preceding work has been published in existing languages or notation, and that

there is not the remotest possibility that the whole corpus of these past works

will be translated into the new tongue or rewritten in the new notation.

To young officers in the Department Middlemiss was very helpful, both in

the field and at Headquarters. I did not have the advantage of working under

him in the field, but I must recall his kindness to me when I offered my first

paper for publication by the Geological Survey. Sir Thomas Holland, then

Director, had introduced the custom of circulating papers for criticism amongst

officers, starting with the most junior and ending with the most senior, before

it went to the Director himself. My paper reached Middlemiss near the end of

its round, and in it he, being a master of English composition, found many

passages that could be better expressed. Instead of commenting on this on the

file he brought the manuscript to me, and we went through it together and made

the necessary improvements before the paper went further.

In spite of his obviously

happy nature Middlemiss occasionally had violent fits of temper, a fault of

which no one was more conscious than he. He was never above telling stories

against himself, and the difficulties his temper got him into. One story may be

permitted here, as it illustrates Middlemiss. I am indebted for it to Sir Edwin

Pascoe to whom it was told by Middlemiss himself. It is the story of

Middlemiss's old bearer and the scones. One day in camp the old man angered him

in some way, with the result that Mlddlemiss sacked him on the spot. The old

servant duly packed up and disappeared. Now the old man was very clever at

making scones and Middlemiss was very fond of scones for tea. That afternoon,

however, there were no scones when Middlemiss returned from his work. When the

next day came and there were again no scones Middlemiss began to wonder whether

he had not been a little hasty. On the third day, to his surprise and delight,

there appeared a dish of his usual scones, and soon after the old bearer

himself carrying on as if nothing had happened. When asked how he dared to come

back after he had been sacked, the old man's answer was; 'Well, Sahib, you and I have been Master and

servant together for over twenty years, and I guess we shall go on being so

until one of us dies!' And they did; it was the old man who died.

GEOLOGICAL WORK During

his long term of service in the Geological Survey of India, Middlemiss spent

but a small proportion of his time at Headquarters, except for the normal

recess season. He was at Headquarters for a short time as Curator of the Museum

and Laboratory and on another occasion was in charge of the offices; whilst at

the end of his service he officiated twice as Director of the Department.

Fortunately for the scientific world he was never a permanently Director, as

his talents did not extend to administrative activty and official

correspondence. Instead he was essentially a field geologist who liked a direct

appeal to the facts of Nature as displayed in the field and elucidated by the

hammer; though he was glad, of course, to confirm and support these results by

work at Headquarters during the recess, by means of the microscope and specific

gravity determinations.

His total service in India can

be divided into three spells. The first, of some ten years' duration, was spent

in North-Western India in the Himalaya, the Salt Range and Hazara. The second

spell was twent-two years long and was devoted mainly to the problems of

Peninsular India, starting with some ten years in the Madras Presidency (the

Salem and Coimbatore districts and the Vizagapatam Hill Tracts) with a Burma

and a Ceylon interlude, followed by some twelve years in charge of the Central

India and Rajputana Party (later the Bombay, Central India and Rajputana Party)

of the Geological Survey of India, with interludes for the headquarters duties

mentioned above. From 1908 to 1913 Middlemiss combined winter work in Central

India and Rajputana with summer work in Kashmir, so that on retiring from the

Geological Survey of India in 1917 he was in trim for his new appointment as

Superintendent of the Mineral Survey of Jammu and Kasmir, a post that he held

until 1930, giving him a total third spell, in Kashmir, spread at intervals

over some twenty-two years; the second and third spells thus overlapped, and

the whole gave him a total of forty-six years' service in India.

The first and second spells

were punctuated by earthquake investigations, namely the Bengal earthquake of

1885, the Kangra earthquake of 1905, and the two Calcutta earthquakes of

1906. Middlemiss's most fruitful

work was done in North-Western India, scientifically during his first

spell in the Himalaya and Hazara, and scientifically and economically during

his third spell in Kashmir, whilst his investigation of the Kangra earthquake

during his second spell acted as a mountain refresher. The middle spell was

not so fruitful, at least as represented by published work, and Middlemiss

appears to have been less happy upon the Archaean rocks of the Peninsula, where

petrographical studies play such a large part and where it is difficult to work

successfully on a broad scale, than he was in ExtraPeninsular tracts,

mainly occupied by younger formations, where broadr stratigraphical

problems prevail and where the age and relationships of the rocks in most cases

have not been so greatly obscured by the operation of intense metamorphic

processes.

JANUARY 1884 WITH OLDHAM TO

JAUNSAR For his introduction to Indian geology Middlemiss was sent

out with R. D. Oldham, whom he joined in the field in January 1884. Oldham was

working in the Jaunsar Bawar tract of the Lower Himalaya behind Dehra Dun, and

as a result of this experience Middlemiss saw not only the Himalayan rock

formations of Oldham's tract, but also the sub-Himalayan tract of Dehra Dun

described by H. B. Medlicottáin his classic memoir of 1864 (Mem. Geol. Surv.

India, 3). Whether Middlemiss actually got

as far west as the Chor Mountain in the Simla Himalaya does not appear, but

that he went close thereto is proved by the water-colour sketch referred to on

page 264, the sketch being dated 1884; and by the reference in his third paper

(Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 22, 29).

From Chakrata in Jaunsar Bawar Middlemiss marched through Tehri Garhwal to

British Garhwal to the east, which with Kumaon still farther east was to form

his hunting ground for some six field seasons.

Middlemiss's work in Garhwal and

Kumaon may be divided into two sections, namely that on the Himalayan

formations, mainly pre-Tertiary, constituting the Lesser Himalaya, and that on

the Sub-Himalayan formations, mainly Siwaliks, forming the outer fringe of the

Himalaya. The latter work was done the later; but as it was brought to complete

fruition in Middlemiss's important and illuminating memoir on the 'Physical

Geology of the Sub Himalaya of Garhwal and Kumaon' (Mem. Geol. Surv.

India, 24, Part 2), a memoir

that has already assumed the position of a classic illustrated with classic

sections, it may be noted first. In this work he mapped completely the

Sub-Himalayan tract from the Ganges on the north-west to the Sarda river on the

Nepal frontier to the south-east,his survey being designed as an extension in a

south-easterly direction of the geological work described by Medlicott. Owing

to the possession of better maps-partly on the scale of l-inch to the mile and

partly, in the Reserved Forests, on the scale of 4 inches to the mile

Middlemiss was able to work in much greater detail than Medlicott, so that he

was able, using his own modest phraseology, to amplify and modify Medlicott's

work.

STRUCTURE OF THE HIMALAYA

The essence of Middlemiss's work was to show that the Sub-Himalaya is divisible

into roughly parallel strips of Siwalik strata separated by reversed faults so

that in every case a younger division is dipping under an older one to the

north-east. At one cross-section he maps five successive reversed faults, of

which two are within the Siwaliks, one separates the Lower Siwaliks (Nahans)

from the Great Limestone of the Lesser Himalaya to the north, and the other

two, still farther north, separate zones of the Himalayan formations. He

regards each of these reversed faults as representing approximately the

position of an ancient shore-line or mountain-foot so that these reversed faults

are at the same time in a certain measure limits of deposition for the

formation immediately south of each (loc. cit. pp. 118-119). They are also

successively younger as one approaches the plains, corresponding with the

deposition of later sediments of the plains side of the range. Consequently the

range continues to grow by fresh additions to itself, like a coral, by the

incorporation of its offspring with itself (loc. cit. p. 133). His reasoning

leads him also to suppose that there must be a reversed fault between the

outermost belt of Siwaliks and the Gangetic alluvium and that consequently the

Himalayan range is still growing. Further, he is confident that before the

deposition of the Siwaliks began the Himalayan range was already in existence

much as we know it now, and that it is highly probable that a barrier of

crystalline rocks existed in Tertiary times between the Sub-Himalayan deposits

of this side and those of Hundes (loc. cit. p. 115).

OSMOND FISHER AND ISOSTACY

As illustrating Middlemiss's readiness

to use new ideas, it is

interesting to note that in discussing the bearing of his work on the theory of

mountain formation he welcomed Osmond Fisher's Physics of the Earth's Crust,

first published in 1881, in which is proposed the hypothesis that the crust of

the earth is in a state of approximate hydrostatical equilibrium so that the

Himalayan mountain range has been rising pari passu with decrease of load, as by denudation it supplied

sediment to the plains at the foot, which themselves have continued to

sink under the burden of increasing load. The term isostasy1 now

used to describe this state of hydrostatic equilibrium was not proposed by

Dutton until 1889, and this term had evidently not reached Middlemiss when he

wrote his memoir, published in 1890.

Both Osmond Fisher and Middlemiss, however, must be described as

isostasists, and in later works Middlemiss uses the term freely.

Pascoe's Footnote #1. It evidently took some time for this

term to reach India. For R. D. Oldham*,

influenced perhaps by Middlemiss's writings, introduced Fisher's views in

discussing the uplift of the Himalaya in the second edition of the Manual of

the Geology of India, published in 1894, without using this term. Strange to

say, this term has not yet reached the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (in

two volumes second edition 1933,

reprint of 1939). It does, however, appear in adjectival form in Chamber's

Twentieth Century Dictionary, dated 1903.

*comment: Oldham's

first mention of any of Fisher's theories is in an article published in 1884 in

the Asiatic Society on fossil synchroneity, in which he discusses conflicting

evidence for changes in latitude through paleoogeographic climate change.

Middlemiss joined Oldham in the field in January 1884 and it is very likely

they discussed Fisher's theories at this time. Fisher had published a Geological Magazine article on

changes of latitude as early as July 1878 which Oldham might have read before

leaving for India. The first

edition of Fisher's book was published in 1881, and its second enlarged edition

in 1894.

ANCIENT RIVERS AND GRAVELS

In our obituary notice of Dr. G. E. Pilgrim we mentioned the suggestion

advanced independently by Pilgrim and Sir Edwin Pascoe, and based on two quite

different lines of approach, that the three main rivers of northern India, the

Brahmaputra, the Ganges and the Indus, were once part of a single river rising

in Assam, flowing north-west along the foot of the rising Himalaya and then

turning south-west towards the Arabian Sea, the course being demarked

demarcated by the distribution of the Siwalik Boulder Conglomerates. This river

was called the Siwalik river by Pilgrim and the Indobrahm by Pascoe. Middlemiss's memoir contains a detailed

survey of a portion of the course of this supposed river. I do not know if

Middlemiss accepted this idea of Pilgrim and Pascoe, but it seems necessary to

note here that his memoir contains a passage that appears to disagree with

their hypothesis. He writes (p. 120):

Nothing is more clearly

demonstrated in the whole range of Sub-Himalayan geology than the connexion

between the position of the debouchure of the present large rivers and the

deposits of Siwalik conglomerate. That being so, we are bound to believe that

these deposits were formed by the direct parents of those rivers, in the places

where they are now found.

This means that the separate patches of Siwalik conglomerate

shown on Middlemiss's map cannot be regarded as sections of a continuous strip

of conglomerate parallel to the Himalaya, but coincide in position with the

places where the ancestors of the present Ganges and Kosi emerged from the

hills2. {Footnote 2 Pilgrim, working on the Panjab section of

the Himalaya came to a different conclusion and found the conglomerates

continuous between the debouchures of the transverse Himalayan streams}.

NAPPES Before he made

his studies of the Sub-Himalayan belt, so happily brought to fruition in the

memoir discussed above, Middlemiss had begun his survey of the belt of Lesser

Himalayan formations lying to the north of the SubHimalayan tract, work

which, though continued at the appropriate season of the year for as long as he

was engaged in this part of India, was not carried to completion before he was

detached for work elsewhere. Nevertheless, Middlemiss's work on the Himalayan

formations is discussed by him in a series of papers in the Records of the

Geological Survey of India, of which the most important is his 'Physical

Geology of West British Garhwal' (Rec.

Geol. Surv. India, 20,

26-40), published in 1887. This paper contains the results of a very careful

survey on the 1-inch scale, with his published map on the quarter-inch scale,

of a tract of country the geology of which was previously unknown. This paper

records in fact the results of the first detailed geological survey of any

portion of the Himalaya. The tract described contains an elliptical area

(within which is Kalogarhi mountain composed of gneissose granite), arranged

parallel to the Himalayan axis, of schistose rocks (Middlemiss's Inner

formation) encircled by a belt of unmetamorphosed sedimentary strata

(Middlemiss's Outer formations) shown by Middlemiss to be at least in part of

Eocene (Nummulitic) and Mesozoic age (Tal beds). Middlemiss decides that the

Inner schistose rocks are older than the Outer, unmetamorphosed, formations, in

spite of the fact that his survey disclosed a very remarkable arrangement of

the rocks, namely that everywhere round the ellipse the encircling younger

Outer formations dipped towards and apparently under the Inner formation, the

older schistose series, so that it was (p. 36):

difficult to get rid of

the first impression already alluded to that the whole is asynclinal trough

with the Outer formations below, and the Inner above. One seems almost driven

to conclude that if a boring were sunk through the centre of the schistose

area, we should inevitably strike the Tal beds below.

Middlemiss resisted this conclusion and instead explained

the structure by showing that everywhere the younger outer formations dipped

under the older inner formation along reversed faults or thrust planes: in fact

he appears to have regarded the Outer formations as being everywhere tucked in

under the Inner formation without supposing that this reversed relationship

extended continuously under the syncline.

INVERTED METAMORPHISM In

our obituary notice of Pilgrim we noted how that great geologist Medlicott in

his discussion of the stratigraphy of the Simla Hills was 'at first tempted to look for grand inversion of

strata', and how by failing to yield to temptation he missed the

truth and left the problem for Pilgrim and West to solve some sixty years

later. If the second great Himalayan geologist, Middlemiss, had accepted the

conclusion that his hypothetical boring would have struck the younger rocks

under the older in the middle of the syncline he would not have left the

problem to be solved by J. B. Auden (Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 71, 407-433 (1937)) some fifty years

later. The combined work of Pilgrim, West and Auden has shown us that the

anomalous relations of geological formations on the grand scale in the Himalaya

are to be explained in terms of repeated overthrust nappes of formations thrust

bodily outwards, i.e. southwesterly, from the Central Himalayan direction

for many miles over the autochthonous formations of the Outer or Lesser

Himalaya, with subsequent denudation producing scattered windows through which

scattered views of the underlying

formations can be obtained. How many of us, if working as long ago as Medlicott

and Middlemiss, would have stood on the brink of these great discoveries and

not have missed them! But these

two geologists laid solid foundations on which others have built. Auden

records the excitement with which he and West independently read Middlemiss's

paper on West Garhwal and wondered if he was really describing a nappe without

realizing it.

In this West Garhwal

paper, and a second paper (Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 20, 134-143) discussing the geology of

the Dudatoli Mountain, Middlemiss describes the distribution of a garnetiferous

aureole round the intrusive gneissose granite and recognizes the strong

resemblance of the Kalo garhi (Lansdowne), Dudatoli and Chor mountai ns both in

rock composition and in geological structure. He regards the granite as intrusive in the schists, but is

very cautious on the source from which it was derived. We know now that these

granites with their associated schistose rocks form parts of nappes of strata

derived from the north-east.

From Middlemiss's Memoir on the

Geology of the Sub-Himalaya one learns that he hoped later to write a

comprehensive memoir on the geology of the Himalayan belt of Garhwal and

Kumaon, of which his papers in the Records, including the two just discussed,

were forerunners. His transference to the Salt Range and Hazara before he had

completed his field surveys of Garhwal and Kumaon would not have been a

geological tragedy if he had been allowed later to return to the Himalaya and

complete the work for this memoir.

Had he done so, would he have failed finally to arrive at the truth and

recognize the large-scale overthrusting, instead of leaving the problem

unsettled for fifty years? Truly

the responsibilities of Directors of Geological Surveys are sometimes very

great, especially when they have to balance the rival claims of a short-term

policy directed to the immediate appraisal of the value of mineral deposits of

possible economic value against those of a long-term policy directed to the

understanding of the geology of a country, upon which ultimately depends

knowledge of the distribution of the known mineral deposits and of the

possibilities of additional discoveries. (See Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 24, 27.)

MOBILITY OF SALT The discovery by

Warth, in 1888, of Cambrian trilobites in the Salt Range of the Panjab was the

cause of Middlemiss being sent there in 1889 and 1890 to investigate this and

other problems that had arisen in that field of research. As a result many more

trilobites were found and Middlemiss produced a brilliant paper on the geology

of the Salt Range 'with a re-considered theory of the Origin and Age of the

Salt Marl' (Rec. Geol. Surv.

India, 24, 19-42 (1891)). At

the time of his visit Wynne's view held the field, namely, that the Saline

series, a term used to designate the Salt Marl and its associated gypsum and

rock salt, was in its normal stratigraphical position at the foot of the Salt

Range, beneath the Purple Sandstone, and therefore either Cambrian or preCambrian

in age. From Middlemiss's careful sections and descriptions it is seen,

however, that the Salt Marl never shows a normal sedimentary contact with the

overlying Purple Sandstone nor with overlying younger beds (Carboniferous

or Tertiary). Having devoted a large portion of his paper to exact description,

in his usual methodical manner, Middlemiss th en allows his speculative

faculties full play and considers the implications of the 'anomalous

quasi-intrusive relations' of the Salt Marl

to other formations. He asks (loc. cit. p. 42):

Can we see in it anything of the nature of

a scum, such as we might picture to ourselves as having partly secreted at the

surface of an ancient untapped magma, and partly resulted from that secretion

by induced changes in the overlying dolomitic strata?

If we can, we have but to give the

substance a gently intrusive or injective impetus, followed by consolidation,

some time during the Tertiary period, to account for all the otherwise perplexing

circumstances under which the salt-bearing beds of the Panjab are found.

From Middlemiss's paper it will be seen that the date of the

disturbances that he interprets in this manner must have been post-Middle

Siwalik (post Miocene) .

Since Middlemiss wrote, intrusive salt domes and plugs have

become a commonplace of geology and such domes, composed of salt of Cambrian

age, but of late tectonic production, have been found widely distributed in

Persia; it is now considered unnecessary to postulate the existence of a

subterranean magma, and geologists are satisfied that the incompetence of

saline beds under tectonic pressure provides an adequate explanation of the

phenomena so graphically described by Middlemiss.

SALT RANGE SALT AGE

CONTROVERSY With

this paper Middlemiss initiated the controversy that is still unsettled concerning the age of the Saline series of the Salt Range, whether it is

Cambrian (or pre-Cambrian), or whether it is post-nummulitic in age and has

acted as the sole of a large-scale overthrust of the whole mass of the Salt

Range over Tertiary saline beds. According to the recent careful re-survey of

the whole of the Salt Range carried out over several years by Mr E. R. Gee of

the Geological Survey of India, the Saline series is of Cambrian (or pre-Cambrian) age and the abnormal relations to other formations so carefully

described by Middlemiss are due to the incompetence and plastic nature of the

materials of the Saline series; all the other stratigraphers who have examined

the ground recently are in accord with Mr Gee on this interpretation. But in

apparent support of the Tertiary age of the salt, Professor Birbal Sahni and

his associates have discovered plant and other organic remains of Tertiary to

Recent age apparently embedded in the Salt Marl and associated beds. The

problem is still, therefore, subjudice,

and to help solve it Professor Sahni has arranged two symposia, one of which

has already been held and its results published. To the first symposium

Middlemiss in his eighty-fourth year has contributed a short note (Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. India, 14, Sect. B, 267-268) in which he

claims that his theory of :

intrusive Salt Marl of the

Salt Range is in harmony with up-to-date requirements and need no longer be

silently dismissed as a rash speculation; even though acceptance of the possible

guess at the end of my paper that an igneous magma may have been ultimately

responsible; is too much to expect.

The flat contradiction between the evidence of stratigraphy

and that of palaeontology referred to above may eventually be resolved by the

recognition that in view of the plastic nature of the saline beds under

pressure, and the solubility of the salt, any fossil remains found therein may

be exotic, and that Saline beds of Cambrian or pre-Cambrian age have been

caused to behave in post-Miocene times in the quasi-intrusive manner described

by Middlemiss and have thereby acquired Tertiary and Recent characteristics in

the form of enclosed Ranikot foraminifera and plant remains of Tertiary and

Recent age.

[The controversy is over: it is now generally accepted that Gee is correct and that Cambrian salt has incorporated later fossils through the process of flow. The salts permits the displacement of the Potwar plateau SSE at about 7 mm/yr]

Kashmir

and the Hazara Syntaxis From the Salt Range,

Middlemiss, in 1890, was sent to Hazara, now in the North-West Frontier

Province [of Pakistan], to study the coal of the Dore River, and this led to

his being sent to make a continuous survey of the whole of the southern half of

Hazara, following the previous disconnected and unfinished work of Wynne and

Waagen, and including a visit to the Black Mountain country during a military

campaign. This work lasted until 1893 and resulted in Middlemiss's splendid

memoir on 'The Geology of Hazara and the Black Mountain', published in 1896 (Mem. Geol. Surv.

India, 26).

Although the mountains of Hazara belong to the Hindu Kush system of

folding with its N.E. strike and are not geographically a part of the Himalayan

system of ranges with their N.W. strike in Kashmir next door to Hazara, yet

geologically the Hazara mountains are composed of rock formations continuous

with those of the Himalayan belts in Kashmir, the sharp bend of strike taking

place north of the hairpin bend of the Jhelum River near Muzaffarabad. As a result, in his survey of Hazara,

Middlemiss was studying stratigraphical belts analogous to those already

partially surveyed in Garhwal and Kumaon. As in Garhwal and Kumaon he divides

his country into zones of disturbance or elongated blocks of formations that

lie parallel to the general strike of the country. He recognizes four such

zones (lo cit.p.87):

NNW (A)

Crystalline and metamorphic zone.

(B) Slate, or Abbottabad zone .

(C) Nummulitic zone.

SSE (D)

Upper Tertiary zone .

He calls A the 'innermost zone' and D the 'outermost zone',

and describes and discusses each separately; and then, comparing them in

respect of the amount of elevation, compression and denudation they have

suffered, he finds that (loc. cit. p. 265):

zone A has been most elevated, most compressed, and

most denuded; whilst we travel south-east through the other zones in order we

find that they have successively been less elevated , less compressed, and less

denuded.

On the south side of each of the three northern zones of

disturbance is a boundary fault by which each zone has been thrust over the

next zone to the south. Middlemiss ranges the zones in order of age A > B

> C > D and regards the boundary faults as similarly successive in age.

Further, discussing how this succession has been produced, he writes (loc. cit.

p. 280):

At stated periods as we

have seen, after a certain packing of the

rocks had taken place, a great block of such rocks has yielded as a

whole and gone sliding over the one to the south, or under the zone to the

north, producing a thrust-plane, and marking off two disturbance zones from

each other.

Middlemiss does not use the term nappe, but as he recognizes

the similarity of the structural arrangements of Hazara to those of the Himalaya

in Garhwal and Kumaon it seems probable that he is really describing, in the

passage quoted above, overthrust nappes, and that a re-examination of Hazara by

one familiar with nappe structure and modern terminology would show this. Also

it seems to follow that had Middlemiss returned to his earlier hunting-grounds

in Garhwal and Kumaon he would have revised his interpretation of such

structures as the Kalogarhi (or Lansdowne) synclinal. [Note: Both nappe

structures, if unfolded, and Middlemiss's sliding, require for their

explanation that the original thrust-planes must have been of low angle. In a

much later paper (1919) resulting from his surveys in Jammu and Kashmir ,

Middlemiss. succeeds In measuring

the inclination of the thrust-plane or reversed fault between the Siwalik and

Miocene zones, of formations ncar Kotli in Jammu . He shows it to be from 12¡

to 15¡ only. (See Rec. Geol. Surv. India,

50, 122. He was the first to demonstrate this fact, which is all

the more important because it relates to what is often termed the Main Boundary

Fault of the Himalaya. (See also Fermor, Rec. Geal. Surv. India, 62,410 (1930).]

In his discussion of his

oldest zone in Hazara, the crystalline and metamorphic zone A, the only zone in

which igneous intrusives have played a part, a zone in which the youngest

formation is his Infra-Trias (now regarded as Permo-Carboniferous in age) and

its metamorphosed equivalents (the 'Tanols or Tanawals'), Middlemiss

points out that this is the only zone in which igneous intrusion has played a

part, and that, therefore, the intrusion of the gneissose granite must have

been pre-Triassic in date and post-Infra-Trias. Middlemiss's next zone, B,

contains rocks ranging in age from his oldest series, his Slate series (Attock

slates), to Tertiary, and none of them are intruded by the gneissose granite .

Whether Middlemiss would have

adhered to his view that the gneissose granite of Hazara was pre-Triassic in

age, if he had considered that the only one of his zones of disturbance that

contains intrusive gneissose granite was a nappe brought into position possibly

from far to the north-west, is of course unknown. What he does do is to enlarge

on the unity of the gneissose granite of Hazara with that of the Central

Himalaya and thereby to ascribe a similar age-to the latter. This leads him to

disagree with the views of MacMahon and others that the Himalayan ranges must

be entirely Tertiary in age. As always, he is cautious, and not dogmatic in

dealing with such a problem. Thus, whilst as before he urges (loc. cit. p. 284)

'the probable great age of the Himalaya as

opposed to the popular ideas that they were the product of yesterday, geologically

speaking', he guards himself against misconception. by referring to

the far-reaching views of the Rev. Osmond Fisher, and says (loc. cit. p. 285)

that it has been gradually becoming evident to all who really examine the

question that the Himalaya are and have been in a constant state of change so

that 'one might say literally that the

Himalaya of to-day are not the same as those of yesterday'. But to

be more precise Middlemiss writes :

Hence in speaking of the

Himalaya of a past geological age or epoch we mean, or at least I mean, that

old representative of them which held about the same position and acted

functionally in the same way as does the mountain-range going by the name of

Himalaya to-day. It may not always have been of the same height as the Himalaya

of to-day . It may sometimes have been represented by long parallel coast

lines, or by archipelagos with chains of mountainous islands following similar

parallel li es, but that it kept certain original features, and that a mountain

core recognizable in its unity" persisted t rough Tertiary, Secondary and

possibly into Palaeozoic times, I have no doubt.

The above is summarized in the final sentence of this

magnificent memoir:

Rome was not built in a day, neither were the

Himalaya either.

As indicating the philosophic attitude of Middlemiss to

every type of problem, it is worth mentioning that although the gneissose

granite of Hazara has demonstrably acted as an intrusive rock to the

sedimentary formations yet Middlemiss is prepared for this rock to be either a

gneissose granite or a granitic gneiss (loc. cit. p. 278) and therefore would

not regard the views of the French school now adopted by many modern

investigators in Britain and elsewhere, namely, that some granites at least may

be thoroughly metamorphosed and melted sediments, as incompatible with the

field evidence. For he refers to the crystalline core of the Himalaya with the

following words (loc. cit. p. 278): whether

we consider it as a thorough granite or as a slumbering gneiss that at one time

became functional as a granite. Middlemiss also draws attention to

the uniformity of petrological characters of this granitic or gneissic rock

right through the Himalaya from end to end 'as

far as observations have gone', as well as in Hazara, and contrasts

this fact with the state of affairs in Southern India, where 'there is no

uniformity whatever as regards the gneissic foundations of the peninsula'

(loc.cit.p.275).

On completing this work in

Hazara Middlemiss was not sent back to Garhwal and Kumaon, as might have been

hoped, but to the Madras Presidency, thus commencing his second or Peninsular

period of work. Instead of next discussing this it seems better to refer first

to his earthquake work and then to his third period in Jammu and Kashmir.

EARTHQUAKES Northern

India, as is well known, is situated on one of the earth's main earthquake

belts, the Indian section striking first north-north-east along the Baluchistan

and North-West Frontier ranges and then south-east and east parallel to the

Himalayan ranges as far as Assam, where it turns south-west to south through

the Assam-Burma ranges. This is a zone of instability, residual from the

Tertiary period, of over-thrusting of Extra-Peninsular India against the massif

of the Peninsula (or vice versa), a period that still continues and will

continue as long as the Himalaya and geologically related ranges are still in

active movement and process of formation. In consequence, India is subject to

earthquake shocks, often of disastrous magnitude, at unequal and at

present unpredictable intervals. In India the field investigation and

study of earthquakes is one of the duties of the Geological Survey.

Consequently, as it is imperative that the evidence presented by earthquake

shocks should be recorded at the earliest possible moment, while it is still

fresh, officers of the Geological Survey of India are liable to find themselves

ordered by telegram at a moment's notice to the scene of some important and

often disastrous earthquake.

Middlemiss during

his career had to investigate the violent Bengal earthquake of 14 July

1885, two mild Calcutta earthquakes of 1906, and the disastrous Kangra

earthquake of 1905. We need discuss only the Kangra earthquake, which was one

of first magnitude and, as judged by loss of human life (over 20,000), one of

the most disastrous of modern times. Middlemiss and three other officers

were despatched to the scene with Middlemiss as senior officer in charge.

Middlemiss, with his previous Himalayan experience, was particularly suited for

the study of this problem, and it fell to him to compile all the evidence

collected from many sources, and as a result he produced another fine memoir (The

Kangra Earthquake of 4th April 1905,

Mem. Geol. Surv. India,

38, 1910).

In this memoir Middlemiss

records all the relevant facts collected and then discusses the cause of the

earthquake. This particular earthquake was peculiar because there were two foci

or epicentral tracts, the larger one, with a maximum intensity of 10 on the

Rossi-Forel scale, being at Dharmsala and Kangra in the Kangra Valley, whilst

the subsidiary epicentral tract, with a maximum intensity of 8, was in Dehra

Dun, with Dehra Dun and Mussoorie as the principal towns. These two foci are

situated where the Sub-Himalayan zone of Tertiary formations embays in a

north-easterly direction into the Lesser Himalayan zone, leaving between them a

south-west-pointing bulge or bastion of Lesser Himalayan formations - that on

which Simla stands. Middlemiss points out that these two embayments are the

only such along the whole length of the Himalaya as far as this is known and

that they must be regarded as places where the Sub-Himalayan belt has not been

straightened out along the over-thrust plane- the Main Boundary fault of the

Himalaya- that separates it from the Lesser Himalayan belt to the north-east.

He mentions other important features connected with the distribution of these

two epicentres, and concludes that the earthquake was of deep-seated tectonic

origin. This view of the origin (loc. cit. p. 340): implies that the shock was

due to a sudden rupture or release of strain occurring among or below the

folded sub-Himalayan formations at two places where the strain was specialy

great owing to resistances to the well-established forward march of the overthrusting

foot of the Himalayan range and where packing, with consequent arching , may

have brought about a certain loss of isostasy.

FOSSILS The

important discovery of the Gondwana fossil plant Gangamopteris by Oetling in

the Vihi district of Kashmir, and subsequent research by R. D. Oldham, Hayden,

Smith Woodward and Seward on this locality or on fossils therefrom had shown

the necessity for a thorou gh examination of such an important area, offering

as it did the possibility of correlating the great freshwater Gondwana

formation of Peninsular India with the richly fossiliferous marine sedimentary

systems of the Himalayan area-two widely distinct geological provinces not till

then ever found in juxtaposition. Middlemiss was entrusted with this task and

spent thereon the summers of 1908 and 1909. In crossing the Golabgarh pass into

Kashmir he found a supremely important section with two fossil-plant horizons

containing Gangamopteris and Glossoperis, of species suggesting respectively

the Talchir and Karharbari beds of the Peninsula. These beds were overlain in

due course by a limestone containing Protoretepora ampla Lonsd. and other

fossils identifying it with the Zewan beds of the Vihi section. Middlemiss had

made a most important discovery and thereby established the Permo-Carboniferous

(Artinskian) age of the lowest beds of the Gondwanas of the Peninsula of India,

and placed these beds in their correct position with reference to the marine

fossil sequence of Kashmir (Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 37, 296 (1909)), and therefore of the

world.

REMAPPING KASHMIR An

incidental result of this visit to Kashmir was the discovery that the

geological map published by Lydekker in his memoir on the geology of Kashmir,

Chamba and Khagan (Mem. Geol. Surv. India,

22 (1883), had been made

on too small a scale, and too rapidly, to satisfy modern requirements;

and as a result Middlemiss had to re-lay the foundations of our knowledge of

the stratigraphy of Kashmir . (See his paper on 'A Revision of the

Silurian-Trias Sequence in Kashmir'. Rec.

Geol. Surv. India, 40, 206-260 (1910).) In addition he returned

to Kashmir in 1910 and rewrote our knowledge of the Pir Panjal, the Outer or

Lesser Himalayan range separating Jammu from Kashmir (Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 41, ll5-144 (1911).) These studies

enabled him to apply to Kashmir and Jammu his ideas of the 'successive zonal

imbrication' of Hazara (loc. cit. p. 136) already mentioned and he succeeded in

recognizing three zones in the part of Kashmir visited by him: (1) the

Sub-Himalayan and Nummulitic zone combined, (2) the Pir-Panjal or Carbo-Trias

zone, and (3) an older zone or zones containing large areas of rocks of

Silurian age. These may be compared with his four Hazara zones listed on page

274.

Although

Middlemiss continued work in Kashmir in 1912 and 1913, with a newly recruited

officer, H. S. Bion, he did not contribute any further papers on this work

before he retired from the Geological Survey of India in 1917 and became

Superintendent of the Mineral Survey of Jammu and Kashmir. Most of his attention in his new

appointment was necessarily directed to the discovery and study of mineral

deposits of economic value. But before we discuss this it is necessary to point

out that in his surveys in Kashmir between 1909 and 1913 Middlemiss cleaned the

slate of previous error and wrote on it the foundations of the geology of

Kashmir to serve as a source of inspiration to his successors. The first

legatee was Bion, who had been inducted into Kashmir geology by Middlemiss in

1912 and 1913 and had nearly completed his description of 'The Fauna of the

Agglomerate Series of Kashmir' when he died

prematurely in June 1915. Some years later this study was issued as a memoir in

the Palaeontologia Indica (n.s, 12, 1--42 (1928)) with an introductory

chapter by Middlemiss. The chief interest of this chapter is Middlemiss's

views on the Panjal Volcanics consisting of the Agglomeratic Slate below and

the Panjal Trap above, with interbedding of trap flows in the upper part of the

Agglomeratic Slate. 'On the origin of the Agglomeratic Slate Middlemiss is not dogmatic, but he inclines to the

explosive volcanic theory, the fragmental beds containing intercalated beds

with the marine fossils described by Bion (principally species of Spirifer and

other brachiopods), the age being Carboniferous (Moscovian and Uralian). The

generally overlying Panjal Traps are of basaltic composition, like the

Deccan Traps of the Peninsula, but are of much greater age. A point of much

interest brought out by Middlemiss is the variable horizon of the Panjal Traps,

so that the horizon of the base of the Trap varies from Middle Carboniferous to

PermoCarboniferous, whilst the upper limit of the Trap ranges from

Permo-Carboniferous to as high as the Upper Trias: so that vulcanicity

began in one neighbourhood in Middle Carboniferous times and eventually ended

elsewhere in the same neighbourhood at the close of the Middle Trias.

Nevertheless Middlemiss regards these Traps as mainly of extrusive origin, a

conclusion acceptable to others who have worked in this country.

WADIA A man' s work

must be judged partly by the extent to which it benefits and inspires those who

follow him. By this test Middlemiss stands high. Bion died young, but D. N.

Wadia succeeded in due course to the legacy and in a series of good papers and

a massive memoir has built well on the foundations of the new geology of

Kashmir laid by Middlemiss, and has been awarded by the Geological Society of

London the same medal, the Lyell Medal, as was awarded to Middlemiss.

MINERALS KASHMIR On joining

his new appointment of Superintendent of the 'Mineral Survey of Jammu and

Kashmir', Middlemiss's primary duty became the investigation of the mineral

deposits of these territories, with the aid of his assistants. His earlier

papers on these minerals are in the Records of the Geological Survey of India

and relate to aquamarines (with L. J. Prashad), petroleum and lignite. Of these

the most important is his paper on the 'Possible Occurrence of Petroleum in

Jammu Province', in which he describes a

structure (which he calls the Nar-Budhan dome) in the form of 'a natural reservoir of the best type, suitable for

the underground concentration and storage of oil' occurring in rocks

of age, structure and lithological character identical with those of the neighbouring

oil region of the Rawalpindi plateau (Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 49, 191 (1919)). From this paper it is

seen that this was not an accidental discovery, but resulted from a deliberate

search based on general grounds of possibilities, and after Middlemiss had made

a visit to the Khaur field. Middlemiss decides that the crest beds of his dome

are almost certainly lower in the series than the crest beds of the Dhulian

dome (now producing oil in the Panjab). Middlemiss's dome has not yet been

tested by any oil company, as far as is known to me, perhaps because of the

absence of seepages, or perhaps from fear of the effects of a fault mapped by

Middlemiss. It was as a part of this work that Middlemiss made his measurement

of the inclination of the Main Boundary Fault at Kotli noticed in the footnote

on page 274.

Reports

from Kashmir In 1922 his

department commenced its own publication under the title of Reports of the

Mineral Survey of Jammu and Kashmir, and between 1922 and 1931 no less than

nine of these reports issued from Middlemiss's pen, amply

illustrated with maps and sections, describing mineral

occurrences of the State examined by him and his assistants, many of the

mineral deposits being fresh discoveries by his department. The titles of these

reports are given in the Bibliography. Most of the mineral s described occur in

association with a remarkable series of elliptical domes of the Great

Limestone, occurring in the midst of the younger Tertiary formation (Murrees)

of Jammu, and in the case of the largest dome, that of Riasi, faulted down

against the Siwaliks. These structures are unique in the whole length of the

Himalaya, and to their upheaval, exposing the rocks underlying the Murrees, is

due the fact that Jammu has many mineral deposits exposed at the surface that

are not known elsewhere along the Himalaya. The Great Limestone was formerly

thought to be of Jurassic age, but Middlemiss equates it with his

Infra-Triassic limestone of Hazara, and it is now regarded as of Permian or

Permo-Carboniferous age. In this limestone are deposits of ores of copper, lead

and zinc

and also barytes; and lying above it is Middlemiss's

Bauxitic series, and also the Nummulitic coal deposits of Jammu, long known but

now more fully disposed, and in addition they differ from all other Indian

deposits of coal in their abnormally low volatiles, so that Middlemiss

describes them as anthracitic or semi-anthracitic in character. The cause of

this is not known, but it is of great interest that the bauxitic deposits that

occur on the surface of the Riasi dome at the next horizon stratigraphically

below the Nummulitic coals are also abnormally low in their volatiles, namely

water. Middlemiss's report on the bauxitic deposits of Jammu Province is

perhaps the most interesting and important of these reports . The Jammu

bauxites differ from the well-known horizontally described in one of

Middlemiss's reports. These coal deposits are peculiar because instead of lying

in the usual synclinal basins they are, of course, anticlinally

disposed and highly hydrated

lateritic bauxites of Peninsular India, which often approximate in composition

to the tri-hydrate, in having a decided dip, namely that of the other rock

formations of the Riasi dome, and in being monohydrated. In addition they are

of unusually high density: yet they are also exceptionally low in iron

contents, and very high in alumina, 70 to 80 per cent being usual against the

50 to 60 per cent of normal bauxites. The-quantities of ore discovered by

Middlemiss and his assistants are large; but when tested, these bauxites prove

to be difficult to dissolve in the Bayer process unless ground exceedingly

fine; and this is difficult because these bauxites are also abnormally hard.

All the minerals of Kashmir suffer from the fact that

Kashmir is distant from the main centres of commerce and industry of India, but

it is difficult to suppose that the State will not one day benefit from

Middlemiss's work and see its oil

structure fully tested and its rich bauxite deposits worked and perhaps smelted

by power generated from the coal found in such juxtaposition or more probably

from a projected hydro-electric installation on the Chenab river. Summarizing

Middlemiss's economic work, one can say that in this he has shown the same

enthusiasm, ingenuity and imagination as in his purely scientific surveys.

PENINSULA GNEISS We

can now turn to the tniddle period of Middlemiss's labours, namely, that spent

mainly in the Peninsula of India, dating from December 1893 until his

retirement from the Geological Survey in 1917, the later years being

punctuated, as already mentioned, by his visits to Kashmir for summer work.

Until 1898 Middlemiss's field work lay in the Salem and Coimbatore districts of

the Madras Presidency, in Southern India, where it was directed primarily to

the study of the mineral resources of these two districts. This work is

represented by four small papers, listed in the Bibliography, devoted to the

magnesite deposits and associated rocks of the Salem district, and to the corundum

deposits of both districts. But Middlemiss also mapped a considerable

tract of both districts for which there is little to show beyond the references

in the Director's annual reports. It seems, however, that he projected a memoir

upon the geology and petrology of these two districts, and wrote at least a

part of it. But the memoir was never completed. It seems probable either that

Middlemiss could not form conclusions satisfactory to himself concerning the

mutual relations of the components of this varied petrological terrain, or else

that his conclusions and speculations thereon were not acceptable to his

Director.

Fortunately, in 1917, Middlemiss became President of the Geology Section

of the Fourth Indian Science Congress held in Bangalore. The venue of the

meeting justified him in his choice of theme for his address, 'Complexities of

Archaen Geology in India' (Journ. and Proc. Asiatic Soc. Bengal, n.s. 13, cxcv-cciv, (1917)). By this

time the Mysore Geological Department had arrived at two main conclusions

concerning the Archaean formations of their State, namely, (1) that the major

portion of nearly everyone of the rock members of the Dharwar system of

Southern India, including the limestones, conglomerates, quartz-iron-ore

schists, and even the quartzites, was of igneous origin, the most

sedimentary-looking rocks being regarded as highly altered lavas and tufaceous

deposits, and (2) that the Dharwar formation, instead of being younger than the

gneissic formations upon which it rests in synclinally disposed strips, was the

older and had been intruded into by the gneissic rocks.

The Salem and Coimbatore districts of Madras adjoin Mysore,

and the Archaean formations stretch from Mysore into Salem and Coimbatore, so

that Middlemiss was entitled to express views on these points based upon his

reading of the evidence in the field. Frankly, both views were unacceptable to

him, and in his address he gives his reasons why; and incidentally he gives us

a glimpse of his past work in Salem, where he had studied carefully the

relationship of the Dharwars to the Hosur gneiss, as he terms the 'Fundamental

Gneiss' of Salem. On the former point I was

able to support Middlemiss in my address to the Geology Section at the Sixth

Indian Science Congress in Bombay (Proc. Asiatic Soc. Bengal, 15, n.s. p. clxxxv (1919) and Mem.

Geol. Surv. India, 70, 109

(1936)); and later the Mysore Geology Department has abandoned its nearly

all-igneous view of the Dharwars (B. Rama Rao, Presidential address to Geology

Section, Indian Science Congress, Indore (1936)).

On the other point, the relative age of the gneiss, as represented by

the Hosur gneiss and the Dharwars, Middletniss admitted that the evidence was

conflicting (loc. cit. p. cxcviii):

Whilst general conclusions

that have great weight are in favour of the younger age of the Dharwars, the

particular section given above might be held to prove just the contrary. Only,

I think, by looking upon the Hosur gneiss as a rock that bas passed through (it

may be) several vicissitudes of solidification and plutonic remelting without

ever having developed much intrusive motion as regards the formations above,

can the above conflicting testimony be harmonized.

Middlemiss's reluctance to accept the Dharwars as older than

the gneisses upon which they rest is due to the apparent absurdity of supposing

that the larger (the gneisses) call be intrusive into the smaller (the

Dharwars), in spite of definite evidence of intrusion at various places. In my

own address quoted (loc. cit. p. clxxvi) above I attempted to resolve

Middlemiss's dilemma with the following words:

To the stratigrapher the

age of an igneous rock dates from the time it solidified, and, if the rock has

been molten more than once, its age must date from the time of its latest

solidification. Thus we see that the 'fundamental gneisses', because they show

intrusive relation s towards the Dharwars, must be regarded as

stratigraphically younger, but nevertheless they must, in part, represent the

older crust-locally modified to a certain extent by assimilation, no doubt-e-on

which, we may assume, the Dharwar sediments were deposited and the Dharwar

lavas extravasated.

Later in this address Middlemiss discusses certain phenomena

in the preCambrian rocks of Idar State in North Bombay, and concludes his

address with a passage worth quoting as showing that Middlemiss was mentally

prepared (see also p. 275) to agree with those who do not regard all granitic

rocks as of igneous origin (loc. cit. p. ccii):

Consequently , it seems to

me, that in dealing with any rock that appears to be of doubtful igneous or

magmatic origin, it is above all nec essary in these days to ascertain in which

direction the cycle of change is moving . To put the matter bluntly-an apparent

ortho-gneiss with its contempor aneous veins may quite as well be an intensely

metamorpho sed sediment with pegmatites formed in it by 'selective

solution' as it may be the extreme, foliated or otherwise modified ,

representative of a granitic, gabbroid or hybrid abyssal injection.

As this address was given in 1917, the year in which

Middlemiss retired from the Geological Survey of India, the passage last quoted

must be taken as summing up his long period of work on the rocks of the

Peninsula .

BURMA Returning now

to chronological order, we must note that Middlemiss's work in Southern India

was terminated 'by his spending the winter of 18991900 in a new field,

namely, the Southern Shan States and Karenni in Burma. His very interesting

Progress Report (General Report of the Geol. Surv. India 1899-1900, pp. 122-153) does not need further comment here as

it dealt with what was only a reconnaissance survey, one however of much use to

his successors.

MADRAS In 1901

Middlemiss returned to the Madras Presidency, but this time to the northern end

known as the Vizagapatam Hill Tracts . Here the only maps available were on the

scale of 1 inch = 4 miles, and, as these wild hill tracts are densely clothed

with forest and but sparsely inhabited, surveying of the accurate type to which

Middlemiss was accustomed was impossible. However, during three field

seasons he mapped a large section of this inhospitable country on a broad

scale, showing long strips of biotite-garnet-gneisses, of the charnockite

series, and of the sillimanite-bearing schists known as khondalites. In

addition he made some interesting petrographical discoveries. One was of a

sapphirine-bearing rock, sapphirine being a very rare mineral that had hitherto

been recorded only from Greenland (Rec. Geol. Surv. India, 31, 38 (1904). The

sapphirine occurred in association with rocks containing also green spinel,

sillimanite, hypersthene and cordierite, the whole assemblage being due to the

mingling of an ultra-basic member of the igneous charnockite series with the

sedimentary khondalite series (see T . L. Walker and W. H. Collins, Rec.

Geol. Surv. India, 36, 1-18 (1908). A

second discovery was of nepheline-syenites similar to miaskite from the Urals

and to the nepheline syenites of Sivamalai in Southern India (T. L. Walker,

Rec. Geol. Surv.India, 36,

19-22 (1908). During his survey of these tracts Middlemiss noticed also that

the high-level laterite was limited to a fairly constant level, surrounding the

hills like a shore-belt, the higher hills behaving like 'islands in the

lateritic age', (See General Report, Gen. Surv. India, for 1902-1903, p. 2S (1903),

BOMBAY & IDAR In

1908 Middlemiss was placed in charge of a new party of the Geological Survey of

India, the Central India Party, a party that worked continuously for many years

extending its field of operations to Rajputana and the Bombay Presidency .

Middlemiss remained in charge of this party at intervals until 1915. Besides

supervising the work of other officers, Middlemiss made his own field of work

in Idar State in North Bombay, at the southern end of the Aravalli ranges of

Rajputana . This work is represented by a good memoir on 'The Geology of Idar

State (Mem. Geol. Surv. India, 44(1),

pp. 1-116 (1921). In this memoir we have another example of Middlemiss's detailed

and accurate work, devoted this time to Archaean and other pre-Cambrian

formations, with careful petrographical studies of the various rock-types . The

importance of this accurate work was seen years later when Dr. Heron, one of

the officers of his party , who succeeded ultimately to the charge of the

Central India, Rajputana and Bombay Party, carried his own surveys southward

from Rajputana to the Idar border and discovered that to make Middlemiss's Idar

work join up with his own (Heron's) Rajputana work he had to adjust the

nomenclature of some of Middlemiss's formations. This proved easy to do without

any re-survey of Idar, in spite of the fact that Middlemiss had been working on

an isolated tract not connected by modern surveys to Rajputana, and in spite of

the fact that Idar proved to be a much more highly metamorphosed portion

of the Aravalli Hills than farther north,

OLDHAM Throughout

Middlemiss's memoirs and reports the reader will encounter much pleasant and

graceful writing. It is not inappropriate, therefore, that almost the last

product of his pen geologically is a grateful obituary notice of R. D. Oldham, the man who first

introduced Middlemiss to field work in India, in the Simla Hills (Quart. J.

Geol. Soc., 93, ciii. (1937).

I hope that the account given in the foregoing pages of

Middlemiss's far reaching investigations, especially in Extra-Peninsular

India - in Hazara, Kashmir, Garhwal and Kumaon - will impress on all who read

that with Middlemiss's death we have lost one of the great figures of Indian

geology, much of whose work is destined to become classical.