Co-seismic strain and the Transition to Surface Afterslip recorded

by Creep-meters near the 2004 Parkfield epicenter.

Roger Bilham, CIRES and Department of Geological Sciences, Boulder

CO 80309-0399

The Mw=6 Parkfield earthquake at 11:15 local time, 28 September

2004 has dealt a possibly fatal blow to the notion that significant surface

slip precedes earthquakes. In 1966, anecdotal reports of surface fissures along

the fault zone had been reported in the preceding week, and a water pipe

fractured 11.6 hours before the mainshock. This offered hope that substantial surface slip may have

occurred had displacement sensors been in place to measure it. In the days,

hours and minutes prior to the 2004 Parkfield mainshock, displacement sensors

were in place, and nothing happened. According to data from eight creep-meters

crossing the fault, the fault remained effectively locked at the detection

level of each sensor (6-20µm) (Langbein et al. 2004, this volume). This absence of surface slip was

accompanied by an absence of significant strain on the borehole dilatometer and

shear-strain-meter array in the region, and by the absence of any unusual

displacements on the GPS array embracing the 2004 epicenter. Although

pre-seismic strain signals seen on some borehole strain-meters suggest that

epicentral strain was not completely indifferent to the pending earthquake, the

signals are close to instrumental noise levels, and pose new challenges for

their reliable future detection.

In contrast to the absence of pre-seismic fault displacement,

the creep-meters all recorded an abrupt co-seismic dextral offset at the time

of the mainshock. The step corresponds to dextral shear of the fault zone, but

in the absence of surface rupture, the creep-meters during early afterslip acted

as extensometers, measuring strain rather than fault creep. The serendipitous location of

creep-meters at Work Ranch both across and eccentric to the fault zone has

provided insight into the development of surface faulting.

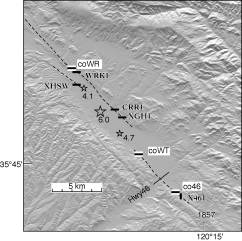

Fig 1. Southern half of the 2004 Parkfield rupture (epicenter=star)

showing the approximate location of surface slip in 1966, and named

creep-meters discussed in the text, (Azimuths of creep-meters indicated by

black bars.) In 2004, surface slip

again occurred near coWR, but as of 28 October 04, not between coWT and

co46. USGS creep-meters are

indicated by solid black bars.

Creep-meters and data processing

The USGS have maintained a creep-meter array in Parkfield since

the 1966 earthquake, increasing the number of sensors over the years to

thirteen (Schultz, 1989; Schultz et al.,1990; Yamashita and Burford,1973). Data

from these instruments indicate that interseismic creep reduces in rate from

more than 20 mm/year north of Middle Mountain to zero South of Highway 46

(Langbein et al, 1990). Ten

of these now record afterslip with a displacement resolution of approximately

20 µm. The three University of Colorado (UC) extensometers discussed in this

article were installed to capture coseismic slip and afterslip at Parkfield,

but were abandoned a decade ago due to funding difficulties. With the

resumption of USGS funding this year, one was re-activated in April, and two

others shortly after the Parkfield earthquake. They measure linear

displacements 30-60 cm below the surface between attachment piers on the flanks

of the fault Each attachment pier consists of steel-rods driven to refusal in

the form of a buried tripod with a maximum depth of 2 m. The length standards of these original

extensometers are solid 1-cm-diameter invar rods that slide within buried

telescopic PVC pipes, although new instruments use 6-mm diameter graphite

rods. The rods are fastened

rigidly to a buried pier at one end.

The rod crosses the fault obliquely at Ĺ30ˇ and motions of its free end

relative to the opposing pier are measured with a

linear-variable-differential-transformer (LVDT). All three Parkfield systems

were equipped with 1" range Schaevitz DCSE 1000 transducers and 12-bit

Onset Microstation data loggers that can operate autonomously from AA alkaline

batteries for a year (Bilham et al. 2004). The locations, and specifications of

the extensometers are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Table 1

Specifications of creep-meters discussed in the text.

|

site |

latˇN |

longˇW |

length |

obliquity |

azimuth |

start |

|

coWR |

35.8587 |

120.3924 |

14 m |

30ˇ |

N76E |

15-Apr-04 |

|

coWRW |

35.8587 |

120.3924 |

2.5 m |

30ˇ |

N76E |

10-Oct-04 |

|

coWRW |

35.8587 |

120.3924 |

10 m |

30ˇ |

N76E |

28-Oct-04 |

|

WKR1 |

35.8587 |

120.3924 |

21m |

40-45ˇ |

N85E |

1978 |

|

coWT |

35.7580 |

120.3003 |

6 m |

30ˇ |

N76E |

2-Oct-04 |

|

coWTW |

35.7580 |

120.3003 |

5 m |

30ˇ |

N76E |

2-Oct-o4 |

|

co46 |

35.7249 |

120.2818 |

14 m |

30ˇ |

N84E |

28-Sep-04 |

|

coNR |

36.8350 |

121.5463 |

8 m |

40ˇ |

N80E |

Mar-04 |

The east component of coWR operated throughout the

earthquake. Following the

development of surface fissures its length was increased westward by 2 m 10-28

October, and to 10 m subsequently. The obliquity of Work Ranch was measured at

40ˇ but is recorded in USGS archives as 45ˇ, possibly assuming a different

local strike for the fault.

Data were downloaded in the field as text files of voltage and

temperature, with a timing accuracy of ±3 s. The voltages, which include a non-linear extension of the

LVDT range from 25.4 to 39 mm, were first linearized to displacements using 6th

order polynomials from laboratory calibration data. Dextral slip is obtained by

dividing the displacement data by the cosine of the fault-crossing obliquity

assuming no distortion of the rod where it crosses the fault zone. The

resulting precision and accuracy in the data is 10 µm. Few spurious data exist

in the raw time series, but mechanical adjustments to transducer positions have

been removed. No temperature corrections have been made to the data. The

diurnal peak-to-peak amplitude in each creep record is less than 80 µm. The

processed and raw data are available as numerical listings at the following

URL: http://cires.colorado.edu/~bilham/WorkRanchSite.htm

Strain and displacement measured at coWR, Work Ranch

Creep-meter coWR supplements data from a USGS/Caltech telemetered

system (WKR1) installed in 1976, which has operated continuously since

installation with a sample rate of 10 minutes. Although WKR1 malfunctioned a

few days before the earthquake, it was repaired a few days later. The Colorado creep-meter (coWR) was

activated in April 2004 to test two new sensors described in Bilham et al.

(2004): one with a high-resolution (6 µm) and 39 mm range, and another with low resolution (1.5

mm) and 3 m range. Both the UC

sensors recorded surface strain at the time of the Parkfield mainshock, and its

subsequent development (Figure 3). The recording rate on the high-resolution

creep-meter was unfortunately reduced from 60s to 300s sampling two days before

the earthquake, although this 5 minute sample rate remains double the rate of

other creep-meters in Parkfield. Following the earthquake its sample rate was

increased to 30 s, a rate that recorded triggered displacements at the time of

the larger aftershocks. The low-resolution creep-meter operated throughout the

earthquake with a 600 s sampling interval.

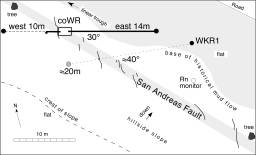

Figure 2. Locations of Work Ranch

extensometers relative to 5 mm to 2 cm wide cracks mapped 21 Oct 2004. The cracks were not evident on 2

October. The 2.5 m west extension

was constructed 10 October and recorded by an independent data logger, after

the fault announced its location. On 28 October it was increased to 10 m

bringing the total length to 24 m.

No cracks were evident in the ground when the Work Ranch

creep-meters were visited 5 hours after the earthquake and again 4 days later,

but irregular cracks at 3-5 m intervals developed subsequently within a

40-m-long, 3-m-wide, swath near the creep-meters (Figure 3). The N58ˇW mean strike of the fault

followed by these en-echelon cracks revealed that the coWR extensometer embraced

(embarrassingly) only half the fault zone. A clear fault zone at this location

is not apparent because it is obscured by what is interpreted to be a small

scale historic mudflow. By 10 Oct an 18-mm-wide, 3-m-long N5W-trending

irregular crack had developed parallel to the western edge of the fiber-glass

vault marking the western extremity of the 14-m-long instrument. This crack tapered to a hairline 50 cm

to the south of the vault, and 1.5 m to its north (Figure 2).

Fault zone fissures were clear in the 40 m zone mapped in Figure 2, but

fissures in the contiguous 100 m to the SE and NW were sparse, an observation

supported by geological mapping of the region reported by Langbein et al.

(2004). The maximum width of

opening of the en-echelon fissures was noted to be approximately proportional

their separation and to their length.

The easternmost and longest fissure had the widest opening and the

furthest distance from the next fissure.

On 10 October the coWR creep-meter was extended 2.5 m westwards

using a 30-cm-deep graphite rod,

and an existing vertical steel pipe as an anchor. On 28 October this temporary arrangement was replaced with a

10-m-long, 60-cm-deep graphite rod, attached to a 2-m-deep buried

steel/concrete pier west of the inspection vault. A 10-cm-range sensor

now records afterslip embraced by the combined 24-m-long graphite/invar

rod system.

That the original UC extensometer incompletely crossed the fault

was suspected before surface fractures were manifest. By 2 October, 10.2 mm of afterslip had been recorded by

coWR, compared to 23.6 mm on WKR1 (Langbein, personal communication, 2004). The

initial efficiency of creep-meter coWR (43%) had reduced to 30% by 10 October

(14.8 mm vs. 48.5 mm) with an

average afterslip velocity half that of the USGS creep-meter. Even with the addition of the westward

extension, the measured dextral slip signal 10-21 October remained 40% smaller

than the WKR1 creep-meter (Figure 3B), requiring the creep-meter to be extended

to 10 m.

An attempt has been made to infer the relative slip recorded by the

west and east-facing creep-meters (Figure 3B). Three assumptions are required. The first is that the WKR1 dextral displacement signal

represents the cumulative dextral shear at this point, as inferred from

post-seismic mechanical adjustments (by John Langbein) needed to bring the

instrument on-line. The second is

that the shear strain above a subsurface dislocation is approximately linear on

the surface. This assumption is

invalid as the subsurface dislocation approaches the surface and the strain-field

narrows to dimensions comparable to the lengths of the extensometers. It is

approximately correct for the early part of the record. An additional

assumption is that creep-meter WKR1 remains straight and 45ˇ to the fault, an

assumption that may be incorrect if a sigmoidal kink in the fault zone (Bilham,

1989) has reduced the obliquity of the WKR1 where it passes through the shear

zone. Twenty-two cm of creep has occurred at Work Ranch in the past 28 years.

The manipulation of these data in this way (explained in the caption to Figure

3B) subject to these various assumptions yields an inexact measure of the

missing slip. However, the

reduction in estimated partitioning, from 40% to less than 30%, is consistent

with the absence of surface cracks in the early part of the record, and with

the location of the measurement vault approximately two thirds of the way

across the surface shear zone, after these cracks were manifest (Figure 2).

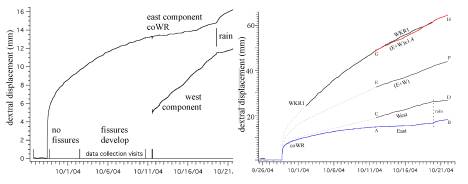

Fig 3A

(left) Extensometer data from coWR, east and west. The east component is shown

as dextral displacement and strain. The west component has an arbitrary offset

and starts 11 October.

Figure 3B (right) Comparison with Caltech/USGS creep-meter WKR1 data (from John Langbein). The absolute

amount of slip that occurred on the east creep-meter is known but that for the

west creep-meter is not, although it can be estimated approximately from

observed velocities (line slopes). The period of overlap AB (east) is added to

CD (west) to obtain the total fault zone shear velocity, EF, for the

16.5-m-long combined extensometer. The slope of GH measured by WRK1 remains 1.4

times greater than the slope of EF, hence the estimated displacement of point F

must be H/1.4. This then

determines the absolute displacement of point D. Dashed lines indicate inferred

displacements.

Fig 3A

(left) Extensometer data from coWR, east and west. The east component is shown

as dextral displacement and strain. The west component has an arbitrary offset

and starts 11 October.

Figure 3B (right) Comparison with Caltech/USGS creep-meter WKR1 data (from John Langbein). The absolute

amount of slip that occurred on the east creep-meter is known but that for the

west creep-meter is not, although it can be estimated approximately from

observed velocities (line slopes). The period of overlap AB (east) is added to

CD (west) to obtain the total fault zone shear velocity, EF, for the

16.5-m-long combined extensometer. The slope of GH measured by WRK1 remains 1.4

times greater than the slope of EF, hence the estimated displacement of point F

must be H/1.4. This then

determines the absolute displacement of point D. Dashed lines indicate inferred

displacements.

Rain occurred in the last few days of the record (Figure 3)

causing a reduction in the rate of opening of the cracks west of the

creep-meter and a corresponding increase in the apparent rate of creep in the

east-going creep-meter. The sum of

the two signals is almost unperturbed by these changes, so that rain appears to

have caused a displacement of the vault position, presumably due to water

entering the surface crack at its western edge. Excavations showed that the soil moistening elsewhere was

confined to the uppermost 10 cm of the soil layer. Below this depth the soil remained dusty.

Creep south-east of the mainshock, coWT & co46

Two creep-meters were activated after the earthquake southeast of

the mainshock. They operate on the

SE branch of the San Andreas fault that slipped in 1966 but where no 2004

fissures had yet appeared by 28 October 2004. The most southerly of these creep-meters is 100 m north of

the USGS creep-meter X461, approximately 1.2 km SE of Highway 46, near an

offset drainage whose probable 1857 offset is discussed by Lienkaemper

(2001). The northerly one is a

restored creep-meter site ("Water Tank"), abandoned due to frequent

flooding, approximately 2 km NE of

Highway 46 in a featureless location in the floor of the Cholame valley. In the first month of afterslip both

creep-meters recorded creep events with 1-3 mm amplitude and 3-8 day duration.

The afterslip decay rate causes the intervals between creep events to increase

with time. Despite the differences

in creep-event amplitude and duration, the afterslip rate at each of these

locations is similar, at approximately 0.3 mm/day.

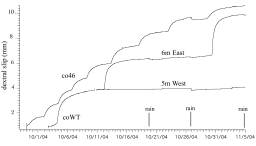

Figure 4

Extensometer data from two locations on the San Andreas Fault segment SE of the

epicenter. Both extensometers were

activated after the earthquake and hence absolute coseismic displacements are

not known. A 23.47 mm extension of

coWT may have occurred coseismically,

as recorded by clean, rust-free surface on an otherwise rusty sensor

clamped a decade ago. The west

coWT extensometer is co-linear and contiguous with creep-meter coWT and records

no change in strain at the time of creep events on the fault.

Figure 4

Extensometer data from two locations on the San Andreas Fault segment SE of the

epicenter. Both extensometers were

activated after the earthquake and hence absolute coseismic displacements are

not known. A 23.47 mm extension of

coWT may have occurred coseismically,

as recorded by clean, rust-free surface on an otherwise rusty sensor

clamped a decade ago. The west

coWT extensometer is co-linear and contiguous with creep-meter coWT and records

no change in strain at the time of creep events on the fault.

Since no nearby geodesy is available to constrain the absolute

amplitude of post-seismic slip at these locations, the displacement datum in

Figure 4 is arbitrary.

Extrapolating the data back to the time of the mainshock suggests that

recording at each site may have started at the end of an earlier creep event of

similar magnitude and duration to the ones that followed. If this indeed occurred the cumulative

afterslip to 21 October is 9-10 mm at each location. However, a coseismic step in the signal may have occurred at

each site, either due to static-strain or to inertial shaking effects. During

installation of coWT its transducer (abandoned in 1993) was found to retain

signs that it had been pulled apart from its attachment to its invar rod

relatively recently. The fresh

rust-free surface had parted 23.47 mm from its retaining clamp, presumably

during the mainshock, but it is not certain how long this fresh surface could

have been exposed underground without rusting.

The coWT creep-meter has two

rods, one extending east and the other west from a central recording

system. Between 2 Oct and 10 Oct a

single transducer recorded their combined signal, but after 10 October the west

component was recorded separately to learn something of the spatial

distribution of surface shear. In the ten days of data available for present

analysis we conclude that the western arm does not cross any part of the active

fault. The west component,

however, does respond to soil moisture changes (rain 18-19 Oct) in the opposite

sense to the fault-crossing east creep-meter.

The coWT creep-meter has two

rods, one extending east and the other west from a central recording

system. Between 2 Oct and 10 Oct a

single transducer recorded their combined signal, but after 10 October the west

component was recorded separately to learn something of the spatial

distribution of surface shear. In the ten days of data available for present

analysis we conclude that the western arm does not cross any part of the active

fault. The west component,

however, does respond to soil moisture changes (rain 18-19 Oct) in the opposite

sense to the fault-crossing east creep-meter.

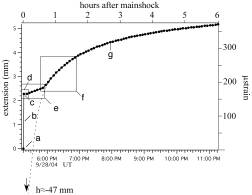

Figure 5 Five-minute samples from creep-meter coWR from before

the mainshock to six hours following the mainshock. The axes are

axial-displacement (not dextral fault slip), and linear strain at azimuth

N94ˇW. Labeled features identified on the record are (a) data point 3 minutes

before mainshock, (b) coseismic extension of 2.28 mm , (c) data point two

minutes after mainshock, (d) first two post-seismic data points may correspond

to instrument overshoot or backlash, (e) a linear ramp at 60 µm/s for Ĺ40

minutes followed by (f) a transitional acceleration to (g), an exponentially

decaying afterslip process. The

exponents in the first hour of this decay process change significantly

suggesting that although the transitional acceleration (f) appears to be only

15 minutes, it may have a duration of up to an hour. Data between 2-6 hours

following the mainshock fit an exponential decay curve to within 0.1 mm

permitting the curve to be extrapolated back to the time of the mainshock (h).

At the time of arrival of s-waves from the hypocenter the extrapolated

displacement applied to the creep-meter corresponds to Đ47 mm.

Coseismic fault strain above the Parkfield rupture

Creep-meters frequently record a process known as triggered slip

whereby a surface fault slips during the passage of strong seismic waves from a

remote earthquake (e.g. Schultz et al., 1990, Bodin et al., 1994). The data discussed here differ from

these observations in that they represent a coseismic step in the plane of the

mainshock-rupture, and close to the hypocenter. Slip on the surface fault has

developed unevenly in time and space in the days following the mainshock

(Langbein et al. 2004), and the Work Ranch site is near the southern end of the

region of maximum surface slip.

The following discussion concerns postseismic strain changes whose

details are thus probably specific to the Work Ranch site.

The five-minute sampled record from Work Ranch increments by

2.279±0.006 mm between the two samples that bracket the mainshock (Figure 5).

The absence of recognizable post-seismic surface rupture in the subsequent

several days is interpreted to signify that the early creep signal does not

measure dextral displacement, nor even fault zone shear. Instead it measures

strain, and, to a first approximation, the strain is equivalent to homogeneous

strain in an elastic half-space. The length of the creep-meter is 14.25±.25 m,

and assuming that large accelerations in the earthquake caused no shift in the

attachment piers (see discussion below), this corresponds to a strain change of

160±3.5 µstrain at azimuth N76W.

Thus, the initial step in the data represents surface-strain

imposed by the M=6.0 rupture at depth, and the subsequent signal represents the

increase in local strain arising from the approach of the shallow rupture

towards the surface, at a rate moderated by presumably velocity-strengthening

rheologies (Marone et al, 1993). Thus, before the development of recognizable

surface fractures four days after the earthquake, the creep-meter acted as a strain-meter (Figure 5). After their development the

extensometer continues to record strain since the fissures do not form a

continuous linear rupture on which displacements can be observed. The distinction is more than semantic

because in the absence of a surface offset there remains some doubt about the

width of the extensometer required to capture the entire subsurface slip

velocity.

Although surface strain had more than doubled (from 160 µstrain to

360 µstrain) 5 hours after the mainshock, no cracks or fissures were

evident. The mean spacing between en-echelon fissures that eventually

developed near the creep-meter (Figure 2) is 4-5 m suggesting that the maximum

crack that could have developed at the end of 5 hours would have been 1.8 mm.

The absence of coherent crack formation at this time suggests that the failure

strain of surface soils exceeds 300 µstrain, or that surface strain at this

time was accommodated in a broad area populated by randomly oriented

desiccation cracks.

Of interest to this study is that no abrupt deceleration in

measured displacement-rate is recorded by coWR that can be ascribed to the

sudden growth of surface cracks. The development of a vertical crack near a

horizontal strain-meter should reduce measured strain, if the crack is produced

by elastic failure. Strain will reduce to zero if the crack is long and deep,

but will be reduced significantly if the crack is comparable in dimensions to

the length of the strain-meter. No reduction is slip is observed in the coWR

data signifying that crack development was not associated with local strain

release, but was driven by additional strain focused in the region by the

afterslip process. Incipient cracks may have been present very early in the

afterslip process with a wall separation too small to be visible, but it is

more likely that the cracks propagated steadily to the surface through a fault

zone of low tensile strength.

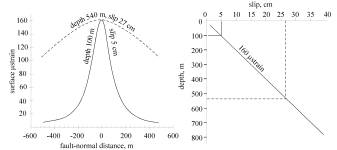

Fig.

6. Strain above a 2-D planar,

buried dislocation extending to 12 km depth. Two illustrative curves (of many) are shown that yield a

maximum strain of 160 µstrain at the surface fault. The dashed line indicates the deepest upper surface of a

uniform dislocation that slips 27 cm, the mean slip inferred for the Parkfield

2004 earthquake.

Fig.

6. Strain above a 2-D planar,

buried dislocation extending to 12 km depth. Two illustrative curves (of many) are shown that yield a

maximum strain of 160 µstrain at the surface fault. The dashed line indicates the deepest upper surface of a

uniform dislocation that slips 27 cm, the mean slip inferred for the Parkfield

2004 earthquake.

That no decrease in strain occurred in the east coWR record after

cracks were manifest requires that crack growth was driven by additional

strain. This additional strain can

be estimated to be of the order of 200-500 µstrain from the growth of strain

recorded by the nearby WKR1 creep-meter, and the western extension to coWR.

I next estimate the size of strain changes anticipated from an

upward propagating shear dislocation embedded in an uniform half-space. The strain at the surface above a

buried planar strike-slip dislocation is a maximum at the future fault rupture

(Figure 5). Using the 160 µstrain

strain-step observed at Work Ranch and the average slip on the fault during the

earthquake (27 cm) as constraints, the closest approach of the Parkfield

rupture to the surface can be calculated. Uniform, planar, 2-D slip between 12

km and the shallow subsurface is an unreasonable constraint, but it reveals

that the upper edge of such a dislocation would need approach within 540 m of

the surface. However, the same

surface-strain can be produced by smaller amounts of buried slip at shallower

depths. For example, 1 cm of

planar slip at 19 m will also produce 160 µstrain of surface strain. Slip presumably tapered towards the

surface and a more realistic model will eventually be possible using additional

strain and displacement constraints.

A second estimate of the shallowest depth of coseismic rupture

follows from the observation that no cracks were visible at the surface up to 4

days after the earthquake, during which time linear strain increased from 160

µstrain to more than 500 µstrain. The precise moment that cracks appeared is

not known, but because the strain increased slowly after the first day I assume

that incipient crack formation occurred when approximately 400 µstrain had been

recorded by coWR. The half-width of synthetic maximum strain is approximately

equal to half the depth to the top of the dislocation (Figure 6), hence the

maximum width of the zone of en-echelon cracks that eventually developed (4 m)

suggests that the dislocation may have approached closer than 2 m to the

surface. A slip of Ĺ5 mm will produce 400 µstrain of surface strain from such a

shallow dislocation, however, the half-width of the strain-field from such a

shallow dislocation, is much smaller than the length of the creep-meter, so

that slip estimated in this calculation is too small by a factor of 2-3, i.e.

an acceptable solution is for 8-14 mm of slip at approximately 5-10 m

depth. The 10-18 mm maximum crack

widths that had developed by 10 Oct at Work Ranch are approximately consistent

with these estimates for shallow slip amplitudes.

Alternative explanations for a coseismic step

The coseismic signal recorded by creep-meter coWR has been assumed

to correspond to separation between its attachment piers, resulting from

tensile soil strain, or dextral fault slip. However, a defect of most soil-embedded objects, unless they

are of identical modulus and density to surrounding soils, is that they tend to

shift relative to their surroundings during high accelerations. Could an

imperfection in the creep-meter have induced co-seismic rod contraction, or

mount-settlement?

Since the accelerations during the earthquake are estimated to be

0.2-0.45 g near Work Ranch (Lanbein et al., 2004), axial forces of up to 36 N

were induced briefly on the eastern attachment point by the 8 kg mass of the

invar rods. Forced displacement of

this mount, or transient buckling of the rod, could thus be responsible for the

observed coseismic signal. The diameter of the telescopic PVC tube is 4 cm, and

hence a 2.6 mm shortening in rod length due to buckling would require a saw-tooth

buckle with an amplitude 34 mm and quarter-wavelength of 2 m. This is considered unlikely because a

spring between the free-end of the rod and the nearby mount maintains the rod

in tension, and shaking would tend to straighten the rod rather than shorten

it. Static loading of the mount by 55 N, causes fewer than 12 µm of

displacement, but the effects of high-frequency prolonged 3-D dynamic shaking

on soils surrounding the low-density vaults are essentially unpredictable. Accelerations at coWT, where a

23.5 mm coseismic displacement may have occurred, were in the range 0.65-1.3 g,

causing nearby liquefaction in the valley floor (Langbein et al., 2004 )

Some of the creep-meters operating in Parkfield use wires in

tension, so that dynamic forces on the end-attachment points from these

length-standards are essentially negligible. Yet the sense of co-seismic strain

recorded by these creep-meters is also tensile (the direction of dextral slip),

including data from the somewhat noisy creep-meter x461, which is installed at

an azimuth where dextral slip results in approach of its two attachment

piers. Coseismic shaking

stimulates a "bow-string" mode and a pendulum mode in suspended

wires, both of which result in apparent shortening of the length-standard, i.e. ground extension. This would have

been transient and probably damped after a few minutes. Unpredictable

settlement of these creep-meter vaults and attachment piers during the dynamic

shaking of surrounding soils presumably means that the precise amplitudes of

these coseismic strain increments are also subject to uncertainty.

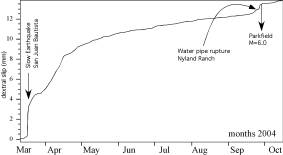

Figure 7

Creep data from Nyland Ranch, north of San Juan Bautista, showing the fracture

of a water pipe caused by a small creep event three days before the Parkfield

earthquake. Although the creep rate here has averaged 7 mm/year for the past

three decades, surface creep following a slow earthquake occurred in March 2004

that almost doubled the annual slip in just 6 months. The effects of the slow

earthquake were confined to the northernmost 10 km of the 125-kim-long creeping

zone.

Figure 7

Creep data from Nyland Ranch, north of San Juan Bautista, showing the fracture

of a water pipe caused by a small creep event three days before the Parkfield

earthquake. Although the creep rate here has averaged 7 mm/year for the past

three decades, surface creep following a slow earthquake occurred in March 2004

that almost doubled the annual slip in just 6 months. The effects of the slow

earthquake were confined to the northernmost 10 km of the 125-kim-long creeping

zone.

Rupture of water pipes before Parkfield earthquakes

Despite its intriguing predictive possibilities, the observation

of a ruptured water pipe prior to the 1966 mainshock was considered by most

scientists to be a random occurrence, the result of slow stressing following

decades of cumulative creep on the surface fault.

However, a pipe did indeed shatter 3 days before the 2004

Parkfield earthquake (Figure 7).

The coincidence occurred on 26 Sept 2004 some 125 km north of Parkfield

where a pipe crosses the northern end of the creeping zone near San Juan

Bautista. Obviously, there is no link between this pipe-break, and the recent

earthquake, and fortunately we possess a quantitative creep record from a

creep-meter fewer than 2 m from the water pipe that records its recent approach

to failure. (Figure 6). Creep on the fault here has proceeded at a rate of 7

mm/year for many decades (Sylvester,2004), interrupted by retardations and

accelerations linked to slow earthquakes in the subsurface (Linde et al.,

1992). A slow earthquake near

Nyland Ranch in March 2004 was followed by 13 mm of surface fault-slip. The

pipe finally failed during a 1 mm creep event on 25 September at Nyland ranch.

Conclusions

No surface fault slip, or significant strain preceded the

September 2004 Parkfield earthquake. The rupture of a pipe before the 1966

Parkfield earthquake can now be classified, somewhat confidently, as a

coincidence resulting from

prolonged stressing in the fault zone in the decades prior to 1966. Coincidently, a similar pipe failure

occurred at Nyland Ranch, at the northern end of the central California

creeping zone, three days before the 2004 Parkfield earthquake. In the absence

of measurements, this might have become another Parkfield legend, but in this

case a nearby creep-meter records the decadal development of creep at Nyland

Ranch at a rate of 7-8 mm/year. A

slow earthquake added an additional 13 mm of slip between March and September

2004. The final millimeter that broke the pipe consisted of a small creep event

that was recorded at about the same time on the XSJ2 creep-meter at San Juan

Bautista.

A coseismic signal present on the creep-meters at the time of the

2004 earthquake, although possibly contaminated by instrument settlement, is

interpreted as tensile strain associated with subsurface rupture. Simple

elastic models suggest that, at Work Ranch, the subsurface rupture must have

approached at least to within 540 m of the surface during mainshock

rupture. This conclusion is

derived from elastic models of surface strain resulting from 27 cm of uniform

slip on a simple planar fault.

Closer approach to the surface with smaller amounts of slip is also

possible. A weak constraint on the

minimum depth and slip permitted by the data is approximately 5-10 m and 8-14

mm respectively. Closer approach

is likely to have produced surface fractures that were not observed until

several days later.

I conclude that surface fissures appeared after measured strain

exceeded 400 µstrain. Because no relaxation in the monotonic increase in strain

was recorded by the eccentric creep-meter at coWR, at the time of their

development, I conclude that cracks and fissures did not release stored elastic

strain when they formed near the surface. Instead their growth appears to have

been driven by additional strain presumably propagating towards the surface

from below. The width of the shear zone of en-echelon surface fissures at Work

Ranch (Ĺ3m) is narrower than the fault-normal width of the newly extended

24-m-long creep-meter coWR (12 m) so that the creep-meter now monitors subsurface creep with acceptable fidelity.

Although a single data point does not allow a unique solution to

the depth of rupture propagation, and the amount and distribution of slip, an

important conclusion suggested by the current study is that an array of simple,

low-inertia extensometers with 1-1000 µstrain recording range, embedded near a

future rupture zone would provide powerful constraints on the geometry of

shallow rupture, and its propagation towards the surface.

Acknowledgements

The creep-meters were funded by NEHRP grant USGS 04 HQAG0008, and

the investigation was undertaken as a Visiting Miller Professor at the

University of California at Berkeley. I thank the Miller Institute for their

generous support during the study.

Roland Bźrgmann has been involved in many aspects of the creep-meters

and their interpretation, and has offered several improvements to the article.

John Langbein has kindly provided processed data from the WRK1 creep-meter, and

has provided many thoughtful insights into observations of the creep

process. I thank Andy Snyder for

his help in coordinating field work.

References

Bilham, R.,

Surface slip subsequent to the 24 November 1987 Superstition Hills, earthquake,

California, monitored by digital creep-meters, Bull. Seism. Soc. Amer., 79(2),

425-450, 1989.

Bilham, R, N.

Suszek and S. Pinkney, California Creep-meters, Seism. Res. Lett. 75(4),

481-492. August 2004

Bodin. P., R.

Bilham, J. Behr, J. Gomberg, and K Hudnut, Slip Triggered on Southern

California Faults by the Landers, Earthquake Sequence. Bull. Seism. Soc. Amer.

84(3), 806-816, 1994.

Langbein , J.

O., R.O Burford, and L. E. Slater, Variations in fault slip and strain

accumulation at Parkfield,

Califonia: Initial results using two color geodimeter measurements, 1984-1988, J.

Geophys. Res,

95, 2533-2552, 1990.

Langbein et

al., 2005 Seism. Res. Lett., this volume.

Lienkaemper,

J. L., (2001), 1857 Slip on the San Andreas Fault Southeast of Cholame,

California, Bull. Seism. Soc. Amer., 91(6) 1659-1572.

Linde, A. T.,

M. T. Gladwin, M. J. S. Johnston, R. L. Gwyther, and R. Bilham, 1996. A Slow

Earthquake near San Juan Bautista, California, in December, 1992, Nature., 383,

65-68.

Marone, C.J.,

C.H. Scholz and R. Bilham, On the Mechanics of earthquake afterslip, J.

Geophys. Res., 96, 8441-8452, 1991.

Schultz, S. S.

Catalog of creep-meter measurements in California from 1966 through 1988. U.S.G.S. Open File Report 89-650.

Schultz, S.,

Mavko, G., and Brown, B., 1990, Response of creep-meters on the San Andreas

fault to the earthquake, in: The

Coalinga, California, Earthquake of May 2, 1983, Rymer, M.J. and Ellsworth,

W.L., eds., U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper, P1487, 409-417.

Smith, S. W.

and M. Wyss, Displacement on the San Andreas fault subsequent to the 1966

Parkfield earthquake, Bull Seism. Soc. Am. 58, 1955-1973, 1968.

Sylvester, A,

(2004). http://www.geol.ucsb.edu/projects/geodesy/nail_lines/

X0070_NYLAND_RANCH_NL.html

Yamashita, P.

A. and R. O Burford (1973), Catalog of preliminary results from an 18 station

creep-meter network along the San Andreas Fault system in central California

for the time interval June 1969 to June 1973, U. S. Geol Survey Open File

Report.