Papers

of Thomas Henry Digges La Touche, 1836-1938,

Geological

Survey of India 1881-1910

British

Library, India Office European Manuscripts Mss Eur C258/x

1880-1890---1891-1892---1892-1895---1896-1897---1897 Great Assam Earthquake---1899---1900-1903 The Directorship Crisis ---1904-1911---

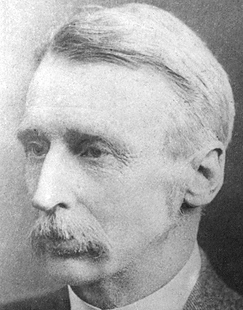

La

Touche (1856-1938) was awarded a degree in Geology in 1880 under Professor Hughes

at St. Johns College Cambridge. He joined the Geological Survey of India in

1881, two years after R. D. Oldham (1858-1936) and was one of the few geologists to complete 25 years in the Geological Survey of India. In late 1890 La Touche proposed

marriage to Anna (Nancy) Handy, and they were married the following year.

Although Nancy accompanied him on his early field work, the arrival of children

and his appointment to remote field areas led to long separations, often

exceeding 8 months each year, and on one occasion lasting 2 years. Field work started in October and continued to

March, and the findings of the work were written up in the recess during the

hot summer months in headquarters in Calcutta. Throughout the time of these

prolonged separations they wrote to each other daily. Tom's letters to Nancy

and the children, who lived initially in the hill stations of India, and

eventually in Ireland, form a continuous diary of important events and affairs

in the office, and in the field. More importantly they provide an illuminating

view of the life style and personal interactions of the dozen Geological Survey

Officers who were based in Calcutta. He acted for Sir Thomas Holland as

Director of the Geological Survey 2 Aug. 1909 and retired in 1910. He died in 1939 Cambridge aged 82.

La Touche's often amusing writings show Carl

Griesbach (Director - died in retirement in May 1907) to be a disorganized and disparaging leader who was

responsible for many frustrations in the Calcutta office 1890-1901, and who

had failed to optimize the potential of his staff. In contrast, R. D. Oldham's

brief spell of leadership in 1897 demonstrates a real interest in optimising

and encouraging the best qualities of his team of geologists. Oldham in 1902 should under normal circumstances

have become the next director following the retirement of Griesbach, as he was merely one year shorter in seniority. But the

energetic and pro-active Viceroy, Lord Curzon, with the bumbling Griesbach as

an example of everything he disliked in the Civil Service, sought to revitalize the search for

minerals and energy resources in India. His choice by default would have been one of three Superintendents, each with two decades of service,

who were next in line for the job: Oldham, La Touche and Middlemiss. He decided against all three. Instead he advertized in the UK for a new man, something he had done successfully in his choice for Director of the Archaeological Survey of India.

It is likely that Griesbach himself was responsible for

sowing doubts in Curzon's mind about the Directorship potential of his three

most senior men. Griesbach disliked Oldham's fastidious attention to geological

detail, which had slowed the mapping of the Rewah region of central

India, and which had caused him to have to referee decisions to mitigate the instability of hillslopes near

Government House, Naini Tal. Griesbach had also had a row with Oldham when he ordered

him to accompany Curzon's secret armed mission to assess a coal field in Oman in October 1901.

Oldham's report (which like his objections to the Oman mission, have yet to

be found) apparently displeased Curzon.

Griesbach's lack of appreciation for La Touche, who was second in line,

was unfounded. He considered La

Touche's Burma mapping to be incompetent (he grudgingly owned the

following year that it wasn't) and in the presence of colleagues rashly attributed his unsavory and unfounded opinion of LaTouche to the mouth

of Curzon's Secretary, Holderness, prompting La Touche to defend his honor by

obtaining a denial from Holderness and a devious and incomplete apology from Griesbach. Griesbach,

no doubt wishing not to lose face over this appalling deceit had the last word with the

administration, and it was no doubt unfavorable to La Touche. The charming

Middlemiss, third in line, who from his numerous written contributions (with the benefit of

hindsight) was the most productive of the three Superintendents, may have been

judged too quiet, and insufficiently ambitious to be considered Directorship

material.

After a long delay caused by a failed search,

Curzon passed over all three men & chose instead Thomas Holland, a bright

and ambitious geologist who was ten years younger, and who had joined only in

1890, but who possessed enormous

energy and talent, echoing the

intellect and industry of Curzon himself.

Tom La Touche's anguish is transparent, as he first encountered rumours of being passed over, and enventually watched his chance to

become the Director of the Geological Survey evaporate, but he chose after much

reflection not to complain.

A highlight of La Touche's

letters is his important contribution to the study of the 1897great Assam earthquake. Two weeks prior to the June earthquake

Oldham, who was Acting Director during Griesbach's furlough in England, asked La Touche to

supervise the Calcutta office while Oldham visited Naini Tal. In this remote hill station Oldham had hardly felt the earthquake and didn't realize the magnitude of its effects until

several days later. On learning of the huge region of destruction Oldham dashed back

to headquarters where "like a bombshell" he dispersed his Survey

officers throughout the epicentral region. Until Oldham's arrival they had focused their efforts on

documenting damage only within Calcutta.

La Touche was dispatched to ground zero in Shillong, an area that he had

mapped in detail more than a decade earlier. His observations, photos and drawings form a substantial

portion of the 1899 Memoir, which was about to establish Oldham's reputation as a

seismologist. Missing from Oldham's memoir are the seismograms that La

Touche obtained from a seismoscope he constructed in the field from bits of

tin, a suspended boulder and a glass photographic plate. Apparently LaTouche's seismoscope continued to operate in Shillong because he mentions it in the days after the 1905 Kangra earthquake when he was asked by Holland to send a similar instrument to Simla.

La Touche also sheds new light on the perceived inadequacies

of Parvati Nath Datta whose appointment in 1888 Henry Medlicott had vigorously

opposed, and whose skills Oldham had criticized in the first year of William

King's directorship, but who Griesbach was slow to suspect of error. It is clear that even after a decade in

the Survey, Datta remained a low fidelity geologist, missing important details

through careless mapping, and occasionally identifying minerals and

rocks incorrectly. Datta appears as a tragic

figure in Burma, and it is easy to feel sorry for him as he tramped, or was

carried, through the villages and hills, irritating local people and fudging his

maps, which required subsequent extensive correction largely by LaTouche. Datta's incompetence led to him being denied appontment to the Superintendent level, although with tactful diplomacy he was permitted to share theposition of Acting Superintendent in 1908 during LaTouche's tenure as Acting Director in Holland's absence.

Throughout the quarter century of his letters La

Touche gives us insights into the mechanics of survey work, the cost of living

and the entertainments and illnesses of officers in colonial India. He tells us little of the native

population, and although several individuals feature in the pages of his diary,

they are mentioned only fleetingly in his letters to his wife.

A word is needed about the methods and

motivation of the geologists of India.

It must remembered that the primary mission of the Geological Survey was

to find coal, and subsequently oil, reserves to fuel the trains and ships that

powered the administration. Of

secondary interest, though of no less pressing importance, was the search for ore deposits. Pure science, then as now, was greeted by the government with a disintersted yawn. Even the broad-minded Curzon saw science as merely a tool to political and economic strength. Science was tolerated because Oldham's father, Thomas Oldham, who had

established the Geological Survey, had persuaded the government that it was not

possible to find coal rationally until the structure and stratigraphy of India

had been mapped. Hence there was a

need for scientific study of the ages of all the rock units and the production

of detailed maps showing their relationship. The awkward mix of economic motivation and scientific

discovery sat uncomfortably on the shoulders of the Director who had to satisfy

both. The absence of radioactive

dating methods meant that the only way to work out the arrangement of rocks,

was to find index fossils, whose evolution and uniqueness provided a natural

clock to reconstruct the chronology of India's geological past. The search for these key fossils was to

take up much of a geologists time.

Where there were no fossils (igneous and metamorphic rocks) the only

recourse was to find the interface between one rock unit and another, in the

hope that it furnished the clue about which came first. Most of the Indian

continent had been mapped by the time that La Touche arrived, and Survey Officers

in the late 19th century were deployed mostly mapping the deformed sedimentary structures surrounding

the Indian craton, in Baluchistan, the Himalaya, and Burma.

Tom La Touche's letters to his family prior to marriage are

irregular and few have survived compared to the daily letters that started in

1891 and are written in a steady stream during his months of separation from

his family in the next 20 years. His letters contain sketches for Nancy and the children, and occasional pressed flowers. Most of the photos he mentions in his letters are missing from the files, but the geological ones can be found in the archives of the GSI in Calcutta. Nancy's replies to Tom

are full of information about the children, less legible and contain fewer

insights about the Survey. With few exceptions they are not transcribed here.

Tom died in 1938 aged 82 in Cambridge, two years after Oldham and his obituary in Q. J. Geol Soc. was written by Charless Middlemiss.

1900-1903 The Directorship Crisis and the secret search for coal in Oman

---

three dashes indicates omitted material,

phrases

in italics are non-verbatim summaries, or explanatory material

some words were undecipherable and are shown in square brackets with a query [?Harrarpur]

some words are now rarely used: bandobast=discipline, forgainst=an opposing position,

Items highlighted in red indicate letters from, or interaction with R.D. Oldham.

items in blue - the secret Oman coal mission found in the 1900-1903 html page