The following pages contain an outline of Oldham's career as recorded by his articles and printed materials

31 July 1858 Richard Dixon Oldham was born in Dublin although it is not clear how much time he spent there. His middle name is his mother's maiden name. Throughout his career Olham was to live under the shadow of his father's achievements and to be frequently confused with him. His father (Thomas Oldham) directed the Irish Geological Survey and founded the Geological Survey of India, and wrote extensively on every aspect of Indian geology. The father is often confused by the unwary, booksellers and scientists alike, with the son.

1867 His father was in England in 1867 ( Obituary Dr. Thomas Oldham, Geol Mag new series Decade II 5 381-384) nine years after the etching of Rugby (below) was drawn. On 13 July 1867 he gave a talk at Rugby on Geological Research in England and India and donated several volumes of the Records of the Geological Survey of India to the school (Report of the Rugby School Natural History Society for the year 1867, published 1868). Richard was 9 at the time but his sister was 16 and his youngest brother only 5, and it is very probable that the Oldham family either established themselves in Rugby at that time, or decided that this would be a good place to bring up the family. His two elder brothers Hugh and Edward would have been of the age to attend Rugby school at this time.

1856 View from Hillmorton road, from west of the Oldham's house in Rugby, from Goulburn, E. M. The Book of Rugby School: its history and its daily life, Crossley and Billington, pp.252, Rugby 1856. Below view of Rugby school in 2007.

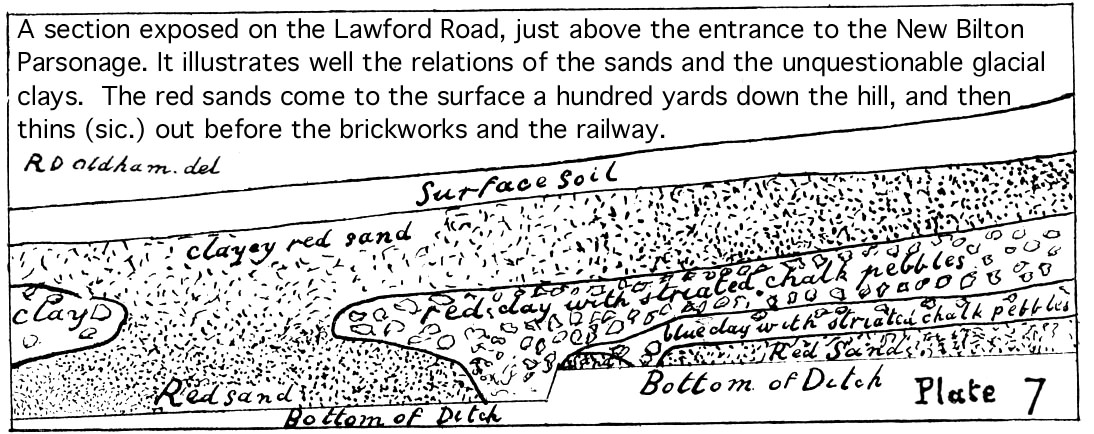

1873-5 School at Rugby In 1873 Richard at age 15 joined the Natural History Society and on 21 June donated a pair ofBoar's teeth from India to the school collection. At the 1st Nov meeting of the society he exhibited 40 photographs of the Punjab. These two events suggest that he may have recently returned from India, especially since his father, Dr. Thomas Oldham, had also recently returned to England. In 1873 his father gave a talk to the Society on the Coal fields of British India. which is published (without the figures) in the Natural History magazine for 1874. What resonates in this talk is his father's vivid description of the drop-stones of the boulder-beds of India which were to figure throughout Richard Oldham's work in India. In 1874, with the inspiration of his father at hand Richard takes over the geological section of the Natural History Society Record (greatly enlarged) as its editor with four articles of his own, two of them substantial. His shorter contributions describe a Rugby road section (without scale) in Oldham's hand, aged 16 (reproduced below with superimposed caption). Note that he emphasizes the presence of chalk pebbles scratched by ice age grinding, conveyed by ice-bergs, and dropped into the blue and red clays underlying an ancient glacial lake in Ice-Age Rugby, something that he and his father no doubt looked at together. His father would have compared and contrasted these with the boulder beds of India. By 1874 Richard Oldham was already a geologist. Both his younger brothers must also have been inspired by their father in that they too exhibited interests in Natural history, with Thomas taking over the geology section and winning the annual prize a few years later, and Henry Yule, also active in the Society going on to become a Professor of Geography in Cambridge. It is not known what became of his elder brothers.

A second minor article describes at length how he oversaw a school team constructing a 3-D geological model of Rugby using clay and Plaster-of-Paris, remarking disarmingly that if parts of the clay model were too high" the superabundance must be taken off by removal not by pressure, for if it be pressed down it will only cause other parts to rise. ...... For tools we had only a scraper or two, and found them quite enough. Fingers are the best tools".

And speaking of tools, in a further section of his geological report he includes one by a school contemporary on the discovery, exhumation and cleaning of a fossil ichthyosaur discovered locally. Again his father, Dr. Oldham, features by demonstrating how to exhume and clean it. To assist Rugby's current and future students to clean this and future fossils Dr Oldham donates 30 chisels, 21 points, 8 files, 4 hammers and a handle with 5 various point sizes to the school.

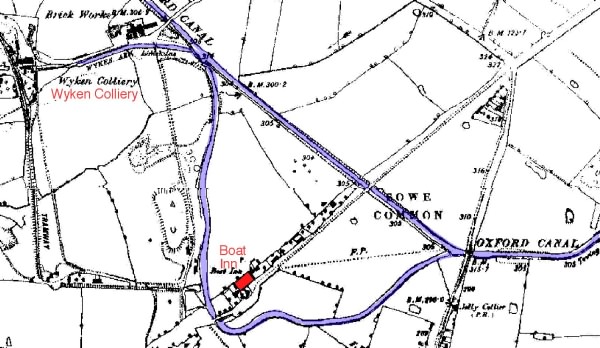

R.D. Oldham's 1874 tour-de-force was an article on Subwealdon Geology that describes in extraordinary technical detail the structure and borehole drilling operations used to investigate the chalk stratigraphy of SE England and France. It is probable that he accompanied his father on an extended excursion to see these operations since they are far from Rugby. The account describes the structure of the Weald (he made a model for inspection to accompany his talk to the school). He describes the reasons for the drilling and the plans made in 1872 to drill through the surface chalk to investigate the subsurface beds. Drilling started in 27 May 1872 and had reached 131 feet by 28 January 1873. In August 1873 on account of slow progress it was decided to abandon percussion drilling in favor of diamond drilling but the machinery was not in place until earlyu the following year. He describes the Brazilian diamonds that were used for the drill heads. The drill hole extended from 320 feet to 670 feet between 7 Feb and 28 March 1874. Oldham's descriptions suggest he personally visited the drilling rig several times since he describes the engineers, and geologists involved. If this is the case he would have been only 14 when the drilling commenced. . His adventures of 1874 are not all dominated by his father's presence. He describes a visit to the Wyken Colliery in Coventry led by the Rev. J.W. Wilson, a geologist who Oldham in his Presidential address to the Geological Society many decades later acknowledges with gratitude ("whom I revere as my first teacher of geology", Q. J. Geol. Soc., 77. lxxx, 1922). In 1874 at age 16 he writes "On Saturday July 5th Mr Wilson took several members of his geology set and others, 13 in all, to see the colliery at Wyken.....a small hut which used to be above the level of the canal but on account of the removal of the ironstone, the ground has sunk several feet below the level of the canal which has necessarily been banked up. We now adjourned to the 'Boat Inn', a cleanly and comfortable roadside Inn near the colliery, where we found an excellent luncheon ready for us, after partaking of which we again mounted our van and returned to Coventry. Here we paid a hurried visit to St. Michaels's church, and ascended the tower, from which a beautiful view of the rich agricultural country around us was obtained."

Wyken colliery which had been mined since 1789 was closed in 1910. The historical 1887 map shows the colliery, the canal, and the Boat Inn. The google map of the same area shows the branch canal has now been filled, but the main canal is still active. http://www.coventry-walks.org.uk/maps/wyken-1887.htm The Boat Inn is still a pub (an armed gang clad in balaclavas robbed it 1 May 2006), The canal that brought the boats to it was diverted to simplify construction of the M6 motorway, but its old path is marked by a muddy tree lined path. The "van" may have been some kind of horse-drawn omnibus. http://www.scienceandsociety.co.uk/results.asp?image=10301569&wwwflag=2&imagepos=1 St Michaels 1480-1939 was bombed during the 1940 raid on Coventry. http://www.historiccoventry.co.uk/cathedrals/oldcathedral.php

1875 This flurry of father and son contributions stops suddenly in early 1875. Presumably Thomas Oldham had returned to India (to resign and retire from the Geological Survey). Writing in May 1876 the editors of the Natural History Magazine for Rugby school state that due to Mr Wilson's illness" and with the unexpected loss of R. D. Oldham", geological activities in Rugby are severely curtailed. The details are missing but although we hear he attends meetings 30 January and on 6 June apparently he is no longer running geological activities in the school. Could this have been illness, or travel? Later that year, in October 1875, he is admitted to the Royal School of Mines, London

1876 In April 1876 Oldham was admitted for continued study at the School of Mines giving his address again as 1 Eldon Place, Rugby. His father retired from directing the Geological Survey of India at about this time and returned to join his family in Rugby with the intention of completing several unfinished articles on Himalayan topics. Details of Oldham's college career are obscure but the 1896 RSM register indicates attendance until 1879 when he left with the qualification ARSM (Associate of the Royal School of Mines). Andrew Crombie Ramsay (1814–91) occupied the University College chair of Geology (University of London) from 1848 until 1851, and become Professor of Geology at the newly opened Royal School of Mines, which had been established as part of the Geological Survey in 1851. (Connor, A., The competition for the Woodwardian Chair of Geology: Cambridge, 1873BJHS 38(4): 437–461, December 2005. British Society for the History of Science doi:10.1017/S0007087405007363) ). John Wesley Judd took (1840-1916) over from Ramsay in Oldham's second year at the RSM. An assistant in the geology department at the time was Frank Rutley (1842-1904) who had written his much referred to "Elements of Mineralogy" in 1874 (12th ed., 1900, 25th edition 1936, and in revised form reprinted in 1970). John Milne attended the Royal School of Mines 1872 in the years preceding Oldham's arrival, and although they became friends 20 years later, there is no record of their having met at the RSM.

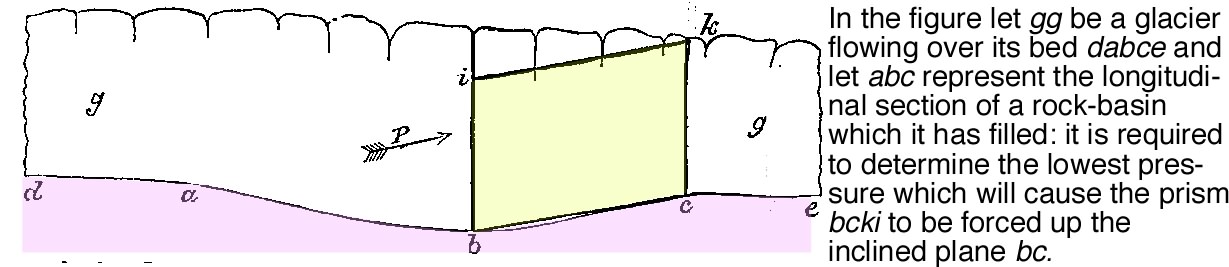

1877 Judd took over as professor of Geology in Oldham's second year at the royal School of Mines. Judd published on several topics (Volcanoes and basalt flows) and is famous for arguing with Geikie about the origin of the basalts of Arran. He also has the distinction of writing the preface to Lyell's posthumous 4th and 5th editions of "Student's Elements of Geology (Baldwin, S. A., (1998), Charles Lyell and the extraordinary publishing history of his works, Geology Today 14 (3), 113–115. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2451.1998.00015.x) . Judd was known as a exceptional teacher who worked closely with his students. The one indication that Oldham may have been an unusual student was that he wrote an article in his last year 1879 on the physics of ice, and its inability to erode after it had obtained a certain thickness (On the modulus of Cohesion of Ice, and its Bearing on the Theory of Glacial erosion of Lake Basins, Phil. Mag. 1879). The article uses Lake Geneva as an example and cites Ramsay, his former Professor.

1878 Death of Thomas Oldham 17 July 1878. One of Thomas Oldham's last scientific contributions was to review the recently published "Geology and Geography of the Colorado Plateau", a review that was published posthumously. His father's estate was less than £2000 and it appears that his small pension may not automatically have been transferred to his widow, judging by a petition from concerned geologist friends to the government. His father's death must must have been quite a blow for a teenager (Oldham was two weeks shy of his 20th birthday). His father's papers were apparently returned to India. It is not known whether Oldham took these paper's with him or whether he followed them after being appointed to a position in the GSI. At about this time Oldham applied for a science scholarship at Emmanual College Cambridge. We lose all track of his elder brothers after their schooldays, except for his younger brother Thomas who wrote for the Rugby School journal in 1878 '79 and '80, and his youngest brother Henry Yule who entered Rugby in 1880 and went on to become a rather unproductive Professor of Geography in Cambridge, and to outlive Richard by 15 years.

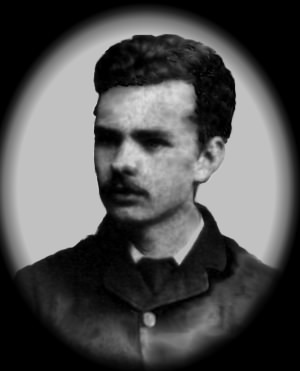

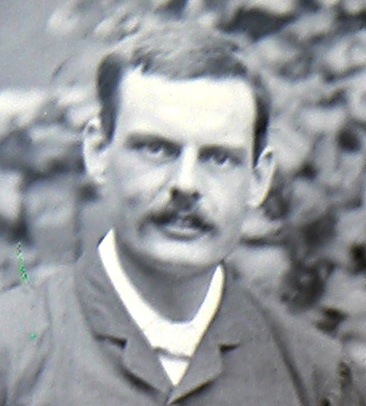

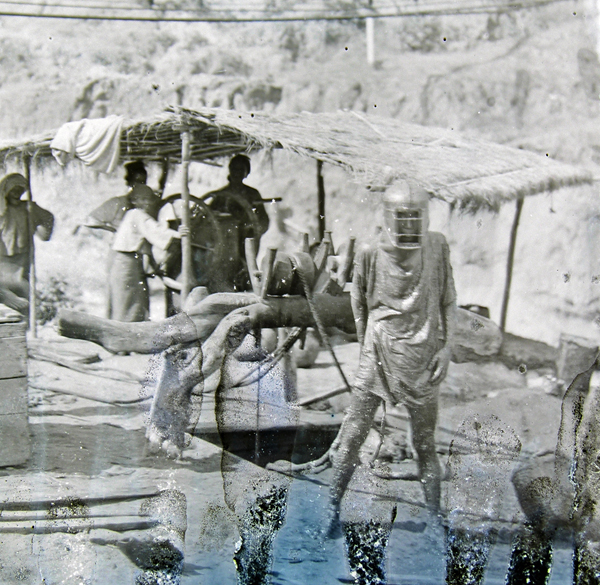

1879 No to Cambridge: Yes to Calcutta: In the winter of 1878/9 Oldham undertook experiments on the crushing strength of ice, and wrote a paper on the implications of its properties that was submitted 25 January, and revised on 15 Feb. He mentions in this article discussions with the seismologist Robert Mallet. On 7 April 1879 Oldham was awarded an open scholarship to Emmanual College Cambridge (an exhibition for 50 pounds tenable for two years to study Natural Science (London Times Tues 8 April 1879.) He declined to accept this position. In early 1879, possibly still at Eldon place, he completed his father's Glossary- a dictionary of geological and mining terms. This had obviously been started by his father but was clearly supplemented by a wealth of mining terms that he had recently been exposed to at the Royal School of Mines. The frontispiece to RD Oldham's glossary is signed and dated 1 May 1879 Rugby. A few months later he accepted a position in India. " Mr Richard D. Oldham was appointed by the Secretary of State as an Assistant [third class] to the Survey, and joined his post on the 17th of December (1879)" (Medlicott Calcutta, Jan 1880 Annual report GSI for 1879." He has taken up work with Mr. King in the Godavari Valley. [The Godavari is the longest river in India emanating from the western plateau and disgorging on the Coromadel coast north of Madras]. In addition to the high proficiency in geological studies evinced by Mr. Oldham at college, and afterwards by independent work, we welcome him as the son" of the founder and director of the Geological Survey of India for 25 years. It is not clear what Oldham's independent work consisted of, although it is probable that Medlicott was referring to Oldham's 1878 published Glossary and the article on the physics of ice. The photograph of the 21/22 year Oldham below was found as a much damaged glass plate in the archives of the Geological Survey of India and forwarded to me by Dr. Sujit Dasgupta. It is reproduced with the permission of the Director General of the Geological Survey of India.

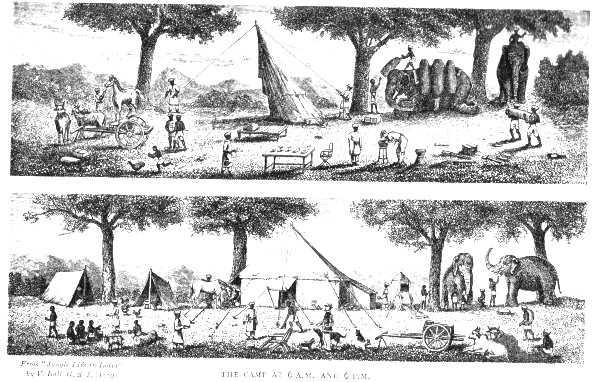

Oldham's field work for the next two decades was to follow the pattern established by the Geological Survey of India and described by Valentine Ball in his Jungle Life in India. The field season was from September to April and the recess June to September, occurred during the monsoon and the months preceding it when it was too hot or too wet to work. Since the annual reports, that describe the assignments of the officers of the survey were issued at the end of January it is sometimes confusing in retrospect to distinguish between last year's field work (the previous season that ended in the spring of the previous year), the field work of the post-monsoon season last year, the field work planned for the future half of the current year, and next year's field work (after the monsoon this year). For this reason, Heron in his 1937 obituary, may have made errors in reconstructing Oldham's movements. A table of Survey Officers 1848-193 lists the career of geologists in India, and a simplified figure depicts the the growth of the Survey 1850-1910. India on average had a dozen geologists, and about one in ten officers died in the field, or retired early from illness.

Oldham's interests lay in fundamental science as seen through the eyes of a stratigrapher and structural geologist. Those of the Geological Survey of India, however, for the decades preceding and following his arrival were focussed on a search for coal and oil, and a quantification of these and other reserves of economic interest. Energy was needed to fuel the railways of India, a growing network of rail-lines constructed primarily to move products for export and import, and only indirectly for the transport of people. Much has been written on the poor management of the railways that led to guaranteed profits for the owners and operators, and which benefited her people little during the 19th century. Geologists followed the new rail lines, mapping the region ±50 km from the frequent stations using elephants and horses to transport camping gear and provisions, but more commonly working on foot. Oldham, like all Indian geologists, marched with their notebooks through many hundreds of miles of Indian deserts, forests, coastlines and mountain passes, searching for exposed rock, and geological contacts, and most importantly for the fossils vital for stratigraphic correlations. Oldham must have written many field notes and letters, some of which may yet be discovered, but the following account is based only on published scientific articles.

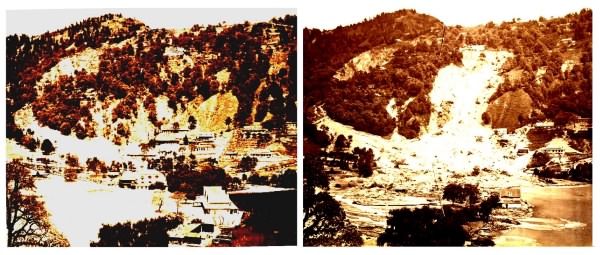

1880 Malaria and a Landslide Immediately on his arrival in India [December, 1879] Oldham was sent to work with William King to assist him map, and become acquainted with, the Gondwana rocks of the Pranhita-Godavari basin in central India. King had been an unsuccessful candidate for the prestiguous Professorship in Cambridge and was destined to become the next Director of the GSI. King's sister had married Richard's cousin/(or uncle) C. A. Oldham a Madras geologist who had died a dozen years previously from guinea worm poisoning. Oldham's work work in the Godavari was also cut-short by illness: "Unfortunately" writes director Medlicott in January 1881," he also underwent initiation to jungle fever [Malaria] ,which he had some difficulty in shaking off. ...under the circumstance Mr. Oldham has been transferred to the Himalayan region, where indeed, his services are more advantageously employed". Oldham was sent to Naina Tal (in the Himalayan foothills ( at 29° 24' N, 79° 28' E 1938m) and serendipitously arrived in time to observe and report on the Naini Tal landslide , a landslide triggered by torrential rain. The resulting article elicits a postscript of praise and additional commentary from Medlicott. The two photos above were taken before and after the landslide (the originals of these are in the British Library). On 1 Dec 1880 as Assistant GSI he becomes a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal & gives his address as Chakrata, in the western Himalaya. (1883 GSI report of the Asiatic Soc. of Bengal). Chakrata (30.69° N 77.86° E at 2100m) is a restricted cantonment region about 90 km north of Dehra Dun. It was established as a British encampment with a Sanatorium in 1869, and now is a training ground for the elite Indian Frontier Force. Oldham used Chakrata as a base for his study of the surrounding district of Jaunsar .

1881 Himalaya and the Burma border. By 1881 his mother Louisa, then 56, elder sister Dorothea, then 28, and youngest brother Henry, then 18, lived at 2 Arnold Villas, Rugby. He presumably finished his father's incomplete articles in India in this year. Medlicott (in his 1882 annual report in Rec GSI dated 28Jan1883) indicates that Oldham " spent a profitable season in the Simla region. To the west of old Sirmur he notices distinct evidence of an actual creep now in progress along the boundary fault, as shown by a continuous line of depression to the south across the spurs and gullies running northwards into Giri"... "It is with much regret that I have interrupted Mr. Oldham's work after so promising a beginning". This may be the first sighting of an active fault in the Himalaya. A geologist was needed to accompany the Manipur/Burma boundary commission and Oldham had volunteered to join them, an offer that Medlicott could not refuse. His Manipur mapping extending India geology more than 100 km to the east, and its addition to the map of India may have prompted him to update the geology of India. Ten years later, in 1891 he completes a Geological Map of India updating all the available data at that time. The map differs little from it second edition that accompanied his Manual of Geology in 1893. In the winter of 1881a Royal Geog. Soc report mentions he was in Manipur and Nagaland with officers of the Burma Boundary Commission there for Christmas 1881. He describes the physical difficulties in conducting geological surveys in the forests of Manipur in an apologetic preface to his Manipur article in 1882, which points out that the forests paths and military escorts permit him few chosen geological traverses.

1882 Simla Oldham returns from Manipur by "marching north to Kohima in the Naga Hills, returning by the Assam Valley." In October he travels between Almora and Mussourie and describes its geology in a short article. He fills an entire issue (Volume XIX) of the Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India by publishing his father's three unfinished articles, and his own report on Manipur from the previous year, which had been ready since July "but there was some delay in procuring" a precise topo map "of the new ground in Manipur". He gathers materials about the effects of the Car Nicobar earthquake of Dec 31 1881 at this time in the form of published reports by the survey department in Dehra Dun.

1883 A wild report from Chakrata Medlicott's annual report for 1883 indicates that Charles Stewart Middlemiss (destined to become the longest serving geologist in India) joined the survey in 28 Dec 1883, and in January has "gone to be broken-in to camp life with Mr. Oldham in the Himalaya". Medlicott indicates that"After a preliminary view of the Simla section Mr. Oldham settled down upon Jaunsar, a British district between the Tons and the Jamna because a large scale map was available there"... "The result has been no small surprise which I shall briefly explain"... "In Jaunsar Mr. Oldham introduces two unconformable and almost wholly detached groups above the Deoban limestone" ....."all this may seem a little wild but a perusal of Mr. Oldham's paper will show that he thoroughly understands what he is about, and has completely protected his position; that if he scorns grooves and is somewhat reckless with antecedent probabilites, he has on the other hand a wholesome faith in close observation and sound reasoning. " He is recorded as non-resident member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 1 Dec 1883 giving his address as Chakrata. The Jaunsar work is published in Rec GSI 16,193-8; and corrected 18 p4.

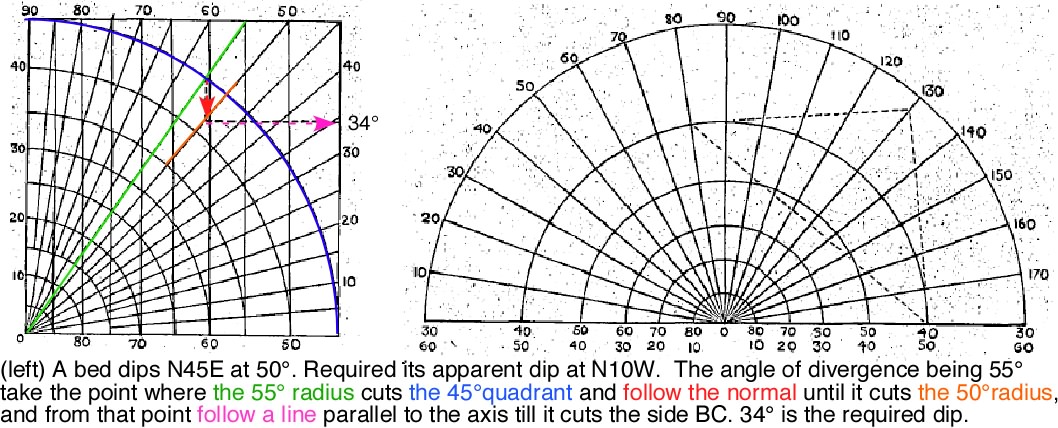

1884 Former Ice Ages in the Himalaya Still based at Chakrata, in the mountains north of Dehra Dun, he describes the distinctive presence of ancient ice-rafted boulder beds that were to be a recurring theme in his future work. Medlicott devotes two pages of his annual report in January 1885 to describing Oldham's necessary revisions to the Himalayan sections that are not yet published. The "Notes on Himalayan Geology and Reconnaissance of Jutogh and Simla" do not come out for two years but in them he recounts his working with Middlemiss ( and Middlemiss reciprocates this fondly a half century later in his Obituary of Oldham, 1937) . While working the slopes of the Himalaya he devised an ingenious graphical method (the oddly labeled protractors below) for determining the true dips of strata from their apparent dips expressed in rock outcrops with divergent azimuths. He gives several examples, one of which I color for clarity. Recall that Knott's 4 figure log tables were unavailable, and the pocket calculator was a century away.

1885 Andaman Islands, Australia and more malaria. In March 1885 Oldham is nominated to the Natural History committee of Asiatic Society of Bengal. William King (acting now as deputy Superintendent GSI) writing p. 3 in the Annual Report for 1884 in January 1885 summarizes Oldham's findings of 1883 and 1884 at length (pages 3-7) and apologizes that they are not yet published and somewhat delayed because Oldham has now been sent to join the Trigonometrical Survey of India who were mapping the Andaman Islands, an opportunity that he feared would not recur. The photo below is of the tide gage on the harbor (c 1885) in Port Blair that recorded the 1881 tsunami. In the summer Oldham delayed his return to Calcutta and obtained a 2 month's extension of duty in order to travel to Australia. He arrived 11 August, traveling to Newcastle with his hosts C.S. Wilkinson and R. F. Murray. He doesn't mention Edgeworth David but David mentions his apparently inspiring visit to sites in the Hunter River Valley, where he recognized evidence for glaciation in Late Paleozoic rocks. It was a 3 week whirlwind visit because a bout of malaria "interfered with my movements and I was compelled to sail from Melbourne on 2 Sept" .

1886 Rajasthan Desert He finished his article on Australian coal deposits at his field-camp at Ajmere, Rajputana, 2 November 1885. He was mapping in the desert regions of Bikanir and Jessalmer, searching for possible coal in what is now westernmost India, where exposures are scarce, and where he had to make his own maps with compass and route-marches. In his 1894 ground-ice article he states: While camping in the desert of Western Rajputana it was a common experience to find, after a clear and cloudless night in January and February, that the water in my wash hand basin was frozen over, and frequently frozen solid. On one occasion, after a cold night, I was surprised to find that the water was unfrozen, and, thinking that perhaps the night had not been so cold as I imagined (I had not then examined my thermometer) I plunged my hands into the water, which immediately became converted into a pasty mass of ice crystals and water. Here ordinary well water, in a basin which was only clean in the common sense of the word, had cooled below freezing point wIthout soldifying; but the occurrence was an exceptional one, and it may well be doubted if it could take place as an ordinary event in the waters of a stream.From the articles he writes and the way in which he is dispatched to confirm the observations of others, Oldham has clearly become the SOI expert in identifying ice-rafted boulder beds and distinguishing them from other forms of conglomerate and breccia. He was selected to go on the Mission to Lhasa, something that clearly excited him , but the mission, according to Medlicott "is postponed indefinitely" (Annual Report for 1886, Rec. GSI 1887 p9), and instead he is sent to the Salt Range to examine stratigraphic correlations and evidence for boulder beds. [Hayden was selected to go when the mission finally departed many years later]. When Oldham was elected a fellow of the Geological Society of London 1 Dec he gave his address as the Geological Survey of India, Calcutta.

1887 An active fault in Kashmir? In 1886 Oldham was dispatched to the Salt Range to confirm the identity of the upper Carboniferous "Speckled Sandstone"which contained two iceberg-related boulder beds, and then visits the Dandcot coal workings there (RGSI 1888 Part 1 Feb.). He then travels to Simla, on to Ladakh and back through Kashmir (p.5). he states that in in May (he states 1888 but writing in 1894 he may have remembered the year incorrectly), he was encamped at Karzok, on the shores of the Tso Moriri, at an elevation of close on 15,000 ft. above the sea. He noticed that the water in a nearby irrigation channel had risen and overflowed its banks yet it should have been at its lowest in cold of the early morning. He observed that a sheet of semi-opaque, whitish ground-ice had formed on the bottom of the channel and so raised the level of the water. The process was fueled by minute crystals of ice, which became entangled in obstructions in the stream and adhered to them and to each other. This led to an article on the formation of ground ice (1894). On his return he stayed for a few days in Srinigar (12 August 1887 in the same residence as La Touche, who had not seen him since 1883). During his return journey he describes the surface expression of an active normal fault with sag-ponds and ridges that he infers to have been caused by a comparatively recent earthquake in Kashmir - this is his second known description of an active fault in the Himalaya and India. (Rec. Geol.Surv of India 21(4), p 159). In early November he investigated rumours of an oil show in Tijarah, near Ulwar ( 27.93N 76.85E, Alwar) only to confirm that the identified combustable layer is artificial and related to village refuse. [Report by William King who takes over as director in April. 1887. In this annual report for 1887 Philip Lake is reported to have joined the GSI ].

1888 Salt Range and a Flexible Sandstone. La Touche reports meeting Oldham returning from camp on 25 March. He is now sent to Kaliana (28° 33' N, Longitude: 76° 12' E) to examine a curious flexible sandstone. His reports on Kashmir and the Himalaya are published, as is his article on facetted pebbles from the Salt Range, and in addition he publishes A bibliography of Indian Geology and sends a copy to the Judd library "With the complements of the author" . The distinction between complement (to match or complete) and compliment (to praise, admire or express courtesy) is a relatively recent refinement in the spelling. In the winter field season P. N. Datta was deputed to be introduced to field techniques by Oldham. Although Datta came with remarkable recommendations from Geikie in Edinburgh and first class degrees from London, Oldham found he had a lot to learn and that his field mapping was sloppy.

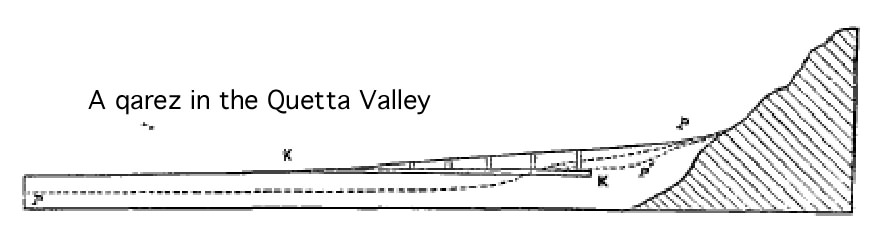

1889 Finding fault with Datta Oldham continued to map the Krol thrust region of the Himalaya with Datta but at the end of this season (May or June) he wrote a memo to King (at about the time the above photo was taken) listing several shortcomings with Datta's geological skills. King had no choice but to ask Datta for an explanaton. Datta's eight page response , fragments of which survive at GSI Calcutta is not at all complimentary to Oldham who is characterised as eager to find fault, to be unpleasantly rude and insulting, and to issue confusing and contradictory field directions. Datta even accuses Oldham of racist slurs and mental abuse. Where Datta admits that Oldham's complaints are justified, as in the imprecise mapping of geological boundaries, Datta pleads illness. Oldham was unsympathetic to Datta's claimed illnesses (lumbago and constant migraine) and dismissed them as imaginary. It is uncertain how the problem was resolved but it is clear that Datta did not live up to Oldham's expectations, and the letters of criticism and counter criticism lodged in files in Calcutta may have cast a pall over Oldham's future managerial potential. Tom La Touche writing a decade letter of his work with Datta confirms that Oldham's opinion of Datta's capabilities. La Touche gives concise descriptions of Datta's mapping in Burma where he incorrect.y identifies mineral (confusing Quartz with Calcite), and misses details in mapping of units, and inthe ordering the stratigraphy in chronological order. After the monsoon Oldham was dispatched to lead a survey party in Baluchistan in a search for coal and oil. His team consisted of Kishen Singh and Hira Lal, and Oldham went on to make them co-authors of his ultimate report. The team found several oil shows and attempted to estimate required borehole depths and possible yields. On page 7 Will King apologizes that "The result of Mr Oldham's work in the Dehra Dun and Simla portion of the lower Himalaya will appear in a memoir as soon as time can be spared from the more pressing investigations in Baluchistan." In writing this William King must have puzzled over one of Datta's most astonishing statements - Oldham is cited as proclaiming that the study of the Himalaya will never lead to anything interesting. The remark must have been cited out of context, possibly referring to the potential mineral wealth in the mountains, for Oldham wrote much that was interesting about the Himalaya both before and after this time.

1890 Sibi, Quetta and the Bolan Pass The mapping of Baluchistan continued for the entire year - his address being given at that time as Quetta. He was in Spintagi 13 Jan 1890 and at camp in Sibi 29 January 1890. Philip Lake was recalled from Baluchistan through ill health and returned to England, and to eventually to resign from the GSI in 1892. Oldham's team mapped large areas of Shiragh and Quetta and the Bolan pass, and for the first time, perhaps because he is working for a team, drafts large geological cross-sections across Baluchistan, showing folding and faulting. These hand tinted maps were published in 1891. Middlemiss remarks that Oldham distrusted cross-sections and never drew them. Indeed only three are known, the first in Rugby hardly counts, the Baluchistan sections are exemplary, and some sketches of the Vindhyan outliers have survived. Oldham was in Camp Sibi 29 January 1890, and the director William King inspected the region near the Bolan Pass with him in Feb. and March 1890.

1891 Quetta to Calcutta In the 1891 census his sister Dorothea is reported matron in a hospital in Devon supervising a dozen nurses, however in May he tells La Touche that his mother lives in Shrewsbury and that his sister works in the infirmary there. Oldham was in Baluchistan until May 1891. La Touche encounters him on his way back to Calcutta on 6 May, and he and his wife are invited to dinner in Calcutta on 5 November. King writes on 31 Jan 1892 (RGSI 1892 p6&7) "Mr Oldham's Party was withdrawn at the end of the working season. His season commenced by his catching up the Kidderai field force at Dhanasar, with the object of examining the reported oil occurrence at Kot Moghul, about 13miles SE of Takt-i-Suleiman. Mr. Oldham's health after almost continuous field work of 18 months, prevented his meeting Sir. R. Sandeman at Apozai, as had previously been arranged, though he tried his best to do so." (RGSI 1892 p9&10) "Mr. Oldham has sent recent reports on the recent deposits of the valley plains of Quetta, Pishin and the Dasht-i-Bedaolet; on the geology of the Thal Chotiali and part of Mari country; on the geology of the country west of the Bolan Pass, and on a tour from Quetta by Kach to Ziaret, Hindubagh.The well-liked administrator of Baluchistan, Sir Robert Sandeman died 29 January the following year in Las Bela where his tomb remains in good repair. Oldham left Quetta a year before the 20 Dec. 1892 Chaman earthquake, the only earthquake on a surface fault to occur during the time of the British Raj. The earthquake features in his subsequent thinking but there is no knowing how he would have interpreted the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, or the 1897 Assam earthquake, had it been he, rather than Griesbach, who had mapped the surface break in Baluchistan at the time. Almost certainly Oldham would have mapped it more thoroughly than Griesbach and its rupture length remains ambiguous as a result. A closer acquaintance with strike slip faulting would have been educational for Oldham, for as we shall later, he was much influenced by the deep causal rupture of the 1897 earthquake, and rejected Reid's elastic rebound hypothesis, possibly the most unfortunate decision of his later career.

1892 A year of writing at Calcutta HQ (RGSI 1892 p54) Based in Calcutta 31 January 1892 "Mr. Oldham continues at the preparation of the new edition of the manual", a task which is to take him most of 1892."Consequent on the retirement of Mr. Foote [Oldham was to write Foote's obituary 25years later], Mr Oldham has been promoted [from Deputy Superintendent 1st grade] to Superintendent effective 1 Oct 1891 (RGSI 1892 p116), and his salary increases from 850 Rp/month to 900 Rp/month(RGSI 1892 p164). La Touche however indicates that on 24 April he met McMahon's son in Quetta, who had met Oldham and Sandeman presumably the previous year. It is probable that Oldham's photo in a group with Middlemiss and King was taken at about this time. He appears as a jolly-looking young man in an ill-fitting jacket, his pith helmet on the ground behind him, in conversation with a colleague or the photographer but looking directly at the camera. Hughes takes over as acting director while King is on leave and comments on the limited quantity of high quality of oil discovered in Baluchistan as discussed by Oldham, and on Page 12 announces that Philip Lake "has been unable through shattered health to return to India and has been allowed to resign". Lake in 1936, became instead Professor of Geography in Cambridge, and in 1936 was to write one of Oldham's obituaries under the initials P.L.

1893 Calcutta/Burma/England Finishing the manual of geology of India in Calcutta, Oldham is able to attend meetings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal on 11 January 1893 and in April 1893, and in March is appointed to the Natural Sciences committee and the Physical Sciences Committee of the R. Asiatic Soc. Bengal. In the 30 April report we learn he "was deputed for a short time to Upper Burma at the end of March" where he assessed water supplies in Rangoon and the Yenang-Young oil field. He was granted Furlough with effect from 1 May 1893 with a salary increase to 950 Rp/month, but according to Will King's report for 1894 he left for England only on 18 July 1893. When his manual on the Geology of India was published 1893 its purchase price of 8 Rupees was almost 1% of his monthly salary. Its current cost if it can be obtained at all, is around $300.

On his arrival in England inthe autumn of 1893 he headed for the Permian and Carboniferous glacial deposits of the Midlands and prepared an article comparing Indian and UK paleo-ice-age deposits "On the origin of the Permian Breccias of the Midlands and a comparison with them of the Upper Carboniferous Glacial Deposits of India and Australia in Q. J. Geol.Soc., 50,463-471, 1894". In December he gave an illustrated talk on the Evolution of Indian Geology to the Royal Geographical Society in London with Archibald Geikie in the audience (11 Dec 1893). Geikie introduced him with words of praise for his father. Early the next year (Jan 18th) he gave a talk on petroleum in India, the first ever overview of Indian oil reserves as far as I can ascertain. This second talk was to the Society of Arts at the newly opened Imperial Institute. [The institute took ten years to construct and was not a great success when it opened in 1893. The tower is all that remains after the institute was demolished in 1953]. Oldham's talk was published in J. Soc Arts and makes interesting reading because from it we obtain glimpses of his experiences in Baluchistan and Burma, and anecdotal accounts of oil drilling successes and failures. ["The Petroleum fields of India (TheTimes of London 18Jan 1894 p.3).

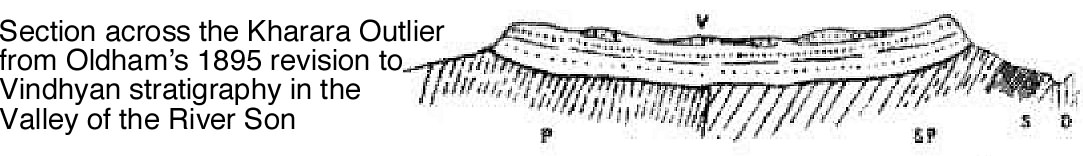

1894 Rewah and the highlands of central India. Back in India"With Bose and Datta" he takes charge of the Rewah party in early 1894 and is working north and south of the Son river (RGSI 28 p87). In his definitive report on the Rewah survey (Mem GSI31(1), 1-102, 1901) he goes to considerable lengths to attribute authorship to each of the many contributing geologists and to explain why it was necessary to integrate their findings. The tinted printed map is 50 km wide strip that runs ENE obliquely across India following the Narbada rift from west of 81° to east of 83°. As usual he focusses on the stratigraphy, morphology and structure and leaves others to handle the petrology and paleontology. His article on the Evolution of Indian Geology is published March 1894.

1895 A considerable time was lost by Mr Oldham He continued to supervise the Rewah field party (working with Mr. Datta ) but possible tones of vexation appear in Griesbach's summary as Director of the GSI in January 1896. He first apologizes for the small area covered by the 1985 Rewah work adding "A considerable time was also lost by Mr Oldham inspecting previous work done by Hughes, Bose and Smith in Rewah, and in reconciling it with his own observations and views" . This was in response to Oldham's careful revision of the stratigraphy where he decides to rename the lower part of the Vindhyan series the Semri series, a name previously used for these rocks. He also examines a coal field in east Rewah. He clarifies these issues in his article on Vindhyan outliers. Then on page 6 we learn that before the rainy season in May and June he is appointed to a committee to report on the safety of Government House Hill, NainiTal, (where he wrote the report on the 1880 landslide ) . Griesbach devotes several pages to this issue even reporting from Oldham's diary ' but the following extract from his diary for June expresses his views in outline: "the facts collected when compared to those already observed on my previous examinations leave me in no doubt that there is a steady downhill creep of the outer portion of the hill for a depth of probably 50 feet...... impressed me the danger of further settlement taking place, which might be sufficient to endanger the house" '. Other members of this committee disagreed with this diagnosis and the government of the NW provinces requested the GSI dirctor, Griesbach, to rule on the matter. Griesbach does so by deciding with the majority, against Oldham. Holland's report is eventually published with a preface by Oldham. The possible availability of Oldham's field diaries is intriguing, and it is sad that none seem to have survived the cleanups, bookworms and general decay of paper materials of Calcutta. One possibility is that any paper with the name Oldham (it must be remembered that his father was the venerated Patriarch of the GSI) may have been squirreled away by well-meaning officers, and separated from the main archives. Unfortunately few of the main archives have survived, and it is not known what has happened to the papers of Thomas Oldham). It was in 1895 that the format of the "Records" of the Geological Survey of India undergo subtle changes. Griesbach shifts the three-monthly summaries to a new short-lived series of General Reports of the Survey of India. For 1895 the Records include terse "Notes from the Geological Survey of India" penned and signed by Oldham. These consist of single paragraph summaries on Rewah, Burma and Kelat (RGSI, 29(3) 69-70), and Mysore - a note on the Kolar goldfield (RGSI, 29(4) 82). The format change was to endure for six years before reverting to its former arrangement, but the numbering of the Records and the Memoirs were never to regain synchronisation.

1896 Calcutta On 8 May he took over as Acting Director while Griesbach went on Furlough. Oldham's mother was visited by La Touche in Shrewsbury 20 June. In late August and early September Oldham was in Ootacamund and 1 October in Calcutta. On 14 October he was in Simla, and in Delhi on the 18th. On 12 Dec 1896 as Officiating Superintendent, Geol. Surv. India he writes an Introduction to the Naina Tal Survey of T. H. Holland's 1897 Report on the Geological Structure and stability of the Hill Slopes around Naini Tal, Calcutta. His permanent UK address in 1896 in the Royal School of Mines Register is recorded as Messrs S. H. King and Coy. 65 Cornhill, London, EC. (This was formerly the address of the firm of Smith Elder and Co who published the works of the Bronte sisters and Darwin and fine Victorian prints.) S. H King & Co. evidently acted as his forwarding address in Europe. The company was taken over by a larger banking firm, Messrs. Cox and Co. which was on 6 Feb 1924 absorbed by Lloyds Bank (Tyson, G. T., 100 years of Banking in Asia and Africa; A history of National and Grindlays Bank Ltd. 1863-1963, Greenway, pp. 245.)

1897 Calcutta and the 12 June earthquake In January we find Griesbach still on furlough and Oldham still as acting Director (Officiating Superintendent) in Calcutta. As Officiating Director he writes the summary for 1896 activites, that starts with his own work. We learn that "during the working season of 1895/6 the survey of Rewah had practically been completed and would doubtless have been finished but for phenomenal unhealthiness of the season" Datta was incapacitated as were many of the field crew. Then we read a rather ambiguous comment concerning Holland. His six year supervision of the Calcutta Geological Museum and Laboratory is terminated "as a decision has been arrived at that it is necessary in the interests of the public service, that he should acquire a practical experience of the ordinary field work of the Survey." This is an odd way to word Holland's re-assignment. He appears to have been in Burma and in Salem in 1896 before going to Ootacamund.

Oldham continues the somewhat telegraphic "Notes" of the GSI that he (apparently) started the previous year: Alumnite from the Salt Range, Attaite from Burma, Petroleum from Upper Burma, Mud Volcano in Tepperah (RGSI 30(2) 110-111) , Dysluite from Madras, Columnite from Haziribagh, and then something that was to change his life for ever - Earthquake of 12 June (RGSI 30(3) 129-132).

June to December 1897 He spent a week in Simla, arriving to inspect the new drainage scheme in Naini Tal one day before the Great Assam earthquake. It is likely he did not feel the earthquake since he was in the Intensity III zone, and did not realize its severity until telegrams and letters had arrived from Tom La Touche who was supervising the office in his absence. The Shillong earthquake caused church spires to tumble in Calcutta, and a huge region near Shillong to be totally demolished. It was the largest earthquake to occur in the entire history of the Raj to that time, now of course eclipsed in magnitude by the 1934 and 1950 Assam events, though these events were hardly felt in Calcutta. Returning to Calcutta almost a week after the earthquake he dispatched Tom de la Touche to the Assam Valley, Shillong, Cherrapunji and Sylhet, and Henry Hayden along the rail line from Calcutta to Darjeeling and towns in northern Bengal on the way. Vredenberg was sent to the region to the west, and Grimes (who was to die in Burma the following year) travelled to E. Bengal and Cachar. P.N.Bose was sent to the Brahmaputra and eastern delta regions later. (see chronological list of Officers) Questionnaires and enquiries were sent throughout India. Oldham's two page report in Part 3 of the Records only a month after the earthquake offers considerable insight into available data and summarizes his immediate findings. In Part 4, the last report of the year, he mentions Eleolite at Sivimalai, and again a short statement on the Earthquake of 12 June. where we learn that telegraph operators encountered electic shocks during aftershocks if they used the Earth as the return signal, but not if they used the second wire of the cable pair (RGSI 30(4) 251-252). He was officiating director up to 24 Nov 1897 during which time (in August and October) he took to the field with his colleagues. During the winter months, after Griesbach had again resumed his directorship, Oldham traversed parts of Garo and the Khasia hills photographing and interpreting the epicentral region in preparation for writing the definitive report on the earthquake that was to be published in early 1899.

1898 Magnitude 8 Findings Oldham spent much of this year compiling and interpreting his findings on the 1897 earthquake. He was granted leave to visit Europe for three months, 16 July to 28 October 1898 (including 14 days on special duty to gather written materials on earthquakes unavailable in India, from the British Museum and the Geological Society of London). While in England he attended the 12 Sept. meeting of the British Association meeting in Bristol and gave a talk there on the earthquake. The seismograms of the earthquake recorded around the world led to him grasping the significance of the increased separation of the three distinct waves from the earthquake with increasing distance from India. He correctly ascribed this effect to the different velocities of compressional waves, shear waves and surface waves. The first 25 pages of his 379 page Memoir 29 in 1899 are devoted to defining the terms used by seismology, an echo of his geological glossary of 16 years earlier. He directs readers to Milne's two books on seismology for more information. In the first page of the Memoir he points out that at the time of the earthquake there was only one person in the Survey available "who had paid any special attention to the subject of earthquakes, or had any knowledge of the nature of the observations required, beyond such as might be obtained from the ordinary curriculum of a geological student." This was presumably a reference to himself. Oldham returned from England after the monsoon in 1898 and with a largely finished 1897 earthquake manuscript which Griesbach recognizes as a remarkable contribution to the subject of seismology in his Jan 1899 report. But back from England in the winter months of 1898 Oldham was sent off directly to finish checking the Rewah mapping work. In 1898 he was appointed a Fellow of the University of Calcutta, an honorary position that his father had been the first to receive (in 1857).

5 April 1899 A change in time. By March 1899 half the 1897 earthquake report had been typeset. On 5 April 1899 Oldham attended the Calcutta meeting of the Asiatic Society of Bengal as a member of the council, and was elected to serve on the Natural History committee. At this meeting he proposed to the assembled members in the form of a carefully reasoned speech ( published as a six page article) that the Asiatic Society should propose to the Indian Government the unification of Indian time 5.5 hours in advance of Greenwich Mean Time. He had been driven to this conclusion because of his research on the felt times of earthquakes and the muddle caused by dozen of different local times throughout the country, casued by local people using the Sun at noon to synchronize their clocks. The railways and telegraph offices had already adopted a unified time system. In the ensuing discussion Thomas Holland who was in the audience proposed that the Asiatic Society Council be instructed to write to the Government with this suggestion, a proposal that was adopted by a vote of 18:1. The council sent a suitably worded letter to the Revenue Department of the India Government on 22 May 1899, and the government responded in November (!) with a statement that the time is not ready for this unification. However, a single time zone for India was indeed adopted 1 January 1906 although Calcutta maintained a separate time zone until 1948, and Bombay informally until 1955. Pakistan shifted its time zone to be 5 hours ahead of GMT in 1951.

5 July 1899 A time for change On 1 May Thomas Holland was appointed Curator of the Calcutta Museum. Two months later Holland was officially appointed as the new Director of the Geological Survey of India (6 July 1899). Significantly, on 5th of May, shortly after this first announcement, Oldham applied for leave [Revenue and Agricultural Department: Notification #1404-50-2]. He was granted official furlough from 11 July 1899 for 18 months. Again, it cannot have been an accident that his furlough actually started 5 days earlier (5 July 1899 i.e. a day before Holland officially took over the Directorship) by availing himself of subsidiary leave from 6-10 July 1899. Clearly he did not want to be around when Holland took over a job that he was well qualified to assume, especially with Holland ten years his junior. Yet in the 1899-1900 GSI General Report p.4 we learn that while on furlough he visited Ceylon and collected numerous rocks and minerals that he presented to the Calcutta museum on his return before heading off to England. Thus, his timing may have been a polite departure to let the new man take over smoothly, rather than a statement of frustration. His 1897 Assam earthquake report was published this year and received wide acclaim. By November he had resigned from his positions at the Asiatic Society of Bengal and had presumably left for Europe to avail himself of his well-earned furlough. This was not to be the end of Oldham's Indian field work, but it was clearly a turning point in his committment to the Geological Survey of India.

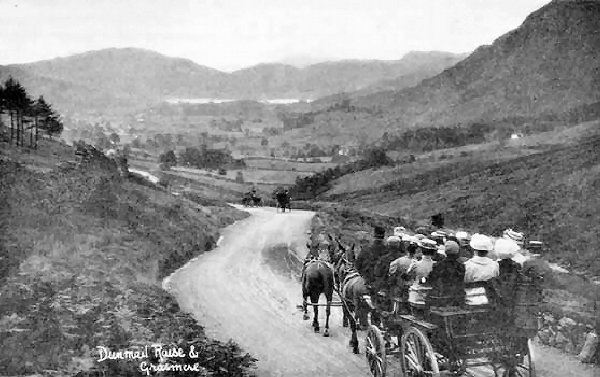

1900 England His Indian salary was three times his salary on Furlough in England. His destination in England is commonly identified as the Isle of Wight where at Shide, south of Newport, Milne had been personally subsidizing the world's first global seismic network with support from the British Association for the Advancement of Science. It was to the Isle of Wight until 1913 that global seismograms were routinely dispatched. We know of no address for him near Shide, however, he lived in tents, hotels or rentals throughout his life, so the absence of an address means little. He spent the last part of his furlough with his sister at Gyllyngvase Terrace, Falmouth (above). During Oldham's almost two year furlough he must have started to think about the utility of seismic waves with different properties as propounded in his 1897 earthquake report. Yet he was still steeped in Geology for he joined the 20-25 Geological Association field trip to Keswick, where he developed his ideas for the origin of the Dunmail Raise (1910 photo below) and attended the Bradford meeting of the British Association 11October commenting on a wide spectrum of topics: the absence of seat-earths in Indian coal measures, on the probable desert conditions that prevailed during the formation of the basal conglomerate of Ullswater, and on the evolving sediment fill of Thirlmere reservoir that might shed light on the hydrology of sedimentation.

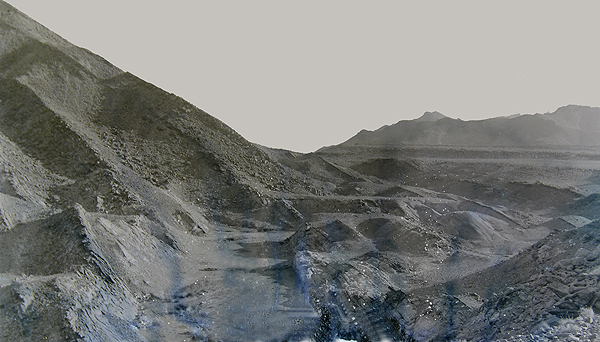

1901 From Falmouth back to glaciers and deserts He attended the Geological Society meeting in London on 9 Jan, and 6 Feb, when he read his Dunmail Rise article. The night of the 31 March 1901 national census of Great Britain found him at age 42 still on furlough from India with his sister (now 49) at 1 Gyllinvase Terrace, Falmouth, Cornwall. In three separate requests he obtained a 6 month and 1 week extension to his furlough because of illness. His job demanded his return to India, however, and on 17 July 1901 it was an announced at HQ (Calcutta) that his services were needed in the Simla Hills in the Himalaya, followed by more work in the Sulaiman hills west of Deri Khazi Khan. He left for the field 29 August 1901, taking striking photos of the mountains, but on 28th October, following the death of Krafft he was sent to inspect a coalfield in Oman. He returned by Mid-December and presumably headed back to Kashmir not to return until 18 March 1902. His numerous half plate photos of Kashmir remain in the GSI in poorly preserved state. Although picturesque this must have seemed dull stuff to the man who had written the book on Indian Geology, and he may have felt marginalized with Holland now directing the Survey of India back in Calcutta. Holland's specialty was petrology and mineralogy and Oldham's was structure, stratigraphy, and earthquakes. Petrology was clearly on the ascent since it could explain the genesis of rocks and the quality of ores. Earthquakes were probably judged of curiosity value only, and certainly of no economic interest.

A photo of the Tisao Valley from Oldham's secret armed mission to Oman, Nov/Dec 1901. Von Krafft's coal seam lies in the 2nd ravine on the left.

1902 Explosion craters in Burma He returned from the Sulaiman ranges on the 18th of March 1902 and compiled records of the 1897 aftershocks which he sent for publication. He was then deputed to Upper Burma to successfully trace the axis of the Yenangyat oil-field anticline. Passing Chindwin he described a train of lakes in volcanic ash and agglomerate that he interpreted as explosion craters. The explosive origin of these was commented on by later geologists. Oldham had developed a taste for photography since the 1897 earthquake and we was intrigued by the native oil extraction methods he saw in Burma.

1903 Kashmir He remained at headquarters Calcutta until 21 March 1903, and then travelled to Jammu and Kashmir returning only 16 October 1903. In March 1903 he participated in a conference in Jammu on the coalfields of Ladda, Sangarmarg, Mehowlgala, SiroValley, Kalakot and Lodhra. From 6-15 April he took over charge of an enquiry into the economic value of the Ladda and Lodhra coal fields [R. R. Simpson, Report on the Jammu Coalfields, Mem.GSI 32(4), 189-26, 1904]. During the summer of 1903 Oldham was engaged on a survey of parts of SE Kashmir (General Report 1903-4) . Two reports followed: one on the Permo Carboniferous of the Zewan beds in the Vihi district, the other on the glaciation of the Sind Valley. Among hisnumerous Kashmir photographs is one of a temple in Srinigar damaged in the 1885 earthquake (below). He published on the diurnal variation of seismicity of 1897 aftershocks, and an article on the Clifton Sandhills of Karachi. These were to be Oldham's final field projects, and he arranged to take early retirement at the end of the year. His official retirement date is set for 1 May 1904 but he is given special 6 months leave making 30 Nov 1903 his last official day in the Geological Survey of India. Davison ascribes this early retirement to illness, and he was certianly very sick in Burma, but one wonders whether Oldham was eager to return to Europe and focus on wider issues. He was 45 when he left India.

1904 From geologist to seismologist. Oldham officially retired at the end of 6 months leave on 1 May 1904 but he had already returned to England by the end of 1903. (General Report 1903-04, p127-9 Holland 2 Jan 1905). On around 5th June Oldham invited La Touche to dine with him at his club in St. James St. in London. On November 4 at age 46 he was elected a member of the Geologists Association in London. (Proc Geol Assoc, 19, 58, 1906). Both Middlemiss and Heron relate that he lived soon after his arrival in England in the Isle of Wight to be close to Milne and his growing repository of global seismograms, however, he is recorded soon after, as living in the village of Shawford just south of Winchester, on the main railway line between London and Southhampton. His obituries all speak of him living in the isle of Whight but there is no record of any rental or permanent address there.

1905 Shawford . Oldham attended London meetings of the RGS, the Royal Soc and the British Association for the Advancement of Science.We lose the detailed thread of his activities since he no longer needed to submit monthly/annual reports to a government body. There is little doubt, however, that his main interest lay in the analysis of seismograms and that he corresponded with observatories throughout the world in the next several years.

1906 It was in this year that he announced his discovery of the radius of the core of the earth at a Royal Society meeting. This article is widely reported in secondary accounts. His quest for the core had started as early as 1899. He was unable to conclude that the core was liquid because he thought he had detected a halving in the s-wave through it, whereas in fact he had measured a reflected s-phase. It was not until 1926 that Harold Jeffreys concluded the core must be a liquid since s waves were not transmitted through it..

In a discussion following a presentation by Freyre on the Rann at the RGS London he was taken by surprise in being asked to contribute, and admits to never having visited the Kachchh region. It is natural that he should have been asked because, though Freyre's presentation precedes Oldham's 1926 study of the 1819 Allah Bund earthquake by two decades, Oldham's authority on the region is already established by his discovery of Baker's Allah Bund map and section in 1898, by his descriptions of Kachchh in the Manual of Geology in 1893 and by the completion of his father's catalog of earthquakes in 1882, which includes the account of the formation of Lake Sindri in 1819.

1907 Fairfield, Shawford, Hants. "La touche to his wife: 5th April 1907, I didn't tell you that I had a letter from Mr Oldham by last mail. He is living at a place called Shawford in Hampshire which seems to suit him, but he says he is not perfectly fit, though much better than when he left India." The house in which he possibly wrote his article on the core of the Earth lies in the pretty village of Shawford on the rail line between London and Southamption. It had been built a few year's previously and as its owner in 1909 he added a bathroom, bedroom, kitchen and scullery (Winchester Rural District Council "Fairfield", Shawford - ref. 39M73/BP567 - date: 1909). The house was a half hour's walk from Shawford station from where he could catch trains to see Milne on the Isle of Wight, or travel to London meetings at the RGS and Royal Society. We know for certain he lived here in 1906 to1908 but it is probable he lived here much longer. The Royal Geographical Society records this as his address until 1912 when it was changed to 8 North Street Horsham. He must have used this address for at least four years, but in the war year edition of the RGS listing of fellows, 1916-1921, he had moved in with his sister to Kew. He wrote a letter from Kew in 1917.

At about this time Oldham obtained the geodetic data of the 1906 earthquake, but not the complete report of, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. From these data he formulated his own version of its underlying cause- a deep seated origin influenced both by his experiences with the 1897 Shillong earthquake, and by incorrect findings that the 1906 hypocenter lay at depths of several tens of km.

In 1907 he published an article on the origin of Himalayan rivers. Writing in Nature in 1907 about river processes he owns " at one time I had a goodly collection of notes of observations made and published by others, but having unfortunately lost this, I shall write about what I have seen myself. " [Nature (1987)77,55,1907 ]. The loss of his notes may indicaate a wholesale loss of other surviving documents.

1908 Oldham is awarded the Lyell medal See citation (he had influenza that day in London) . He receives a letter from Thomas Mellard Reade offering congratulations on the medal, to which he responds 14 January from Shawford.

11 Dec1908 Andrew Lawson and G.K. Gilbert (writing from San Francisco) send Oldham a copy of their 1906 earthquake report."Mr. R. D. Oldham, Fairfield, Shawford, Hants, England. Dear Sir: I take pleasure in having forwarded to you a copy of volume one of the report of the State Earthquake Investigation Commission together with the accompanying atlas, which please accept with the compliments of Mr. G. K. Gilbert and myself. The volume will be shipped through the medium of the Smithsonian Institution and may, therefore, reach you somewhat later than this letter" On 2 Dec 1908, however, Oldham had already addressed the Geological Society of London with his interpretation of the 1906 earthquake, citing the 1907 Hayford geodetic report of the earthquake which he had time to digest and expand upon. His interpretation of the geodetic data is lengthy, first summarising the results of the investigation and then constructing a mechanical model to illustrate his favoured mechanism. Time has shown Oldham to have been substantially wrong, not so much for invoking a two-layer mode, but for assuming that the lower layer which we now know creeps steadily beneath the crust, to have shifted suddenly, thereby driving faulting in the crust. He was unable to imagine that slow deformation stressed the crust towards failure. This mistaken notion prevented him from accepting Reid's elastic rebound model as described in the Lawson report on his way to him from the Smithsonian. Oldham was to hold on to these mistaken ideas about earthquake source mechanisms for the rest of his life. This led in 1926 to his erroneous re-interpretation of the 1897 earthquake in ways further from the truth than expressed in his 1899 report.

1909 Return to Burma Publishes article on the Italian earthquake of 28Dec1908, another on "the New Geography" and subsequently another comparing recent earthquakes. In his "new geography" he expresses his opinion that the interior of the earth can now be explored using earthquakes and seismic waves, as opposed to the surface study available up until that time. 16 Jan 1909 sends letter from Fairfield Shawford Hants to Percy Fry Kendall congratulating him on receiving the Lyell medal. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/library/spcoll/handlists/052MS570Kendall.pdf. His visit to Burma occurred between Oct 09 and March 1910. La touche indicates that he arrived in Bombay 29 October 1909 and took the train to Calcutta arriving 31 Aug. On 7 November he travelled to Burma consulting for the Burma Oil Companyand on the 25th asked La Touche whether he could find a reliable field assistant to travel to join him there. On 10 Dec La Touche received a letter from him indicating that the weather was bad and the roads were muddy and travel difficult. Things had improved by mid January and he indicated that he would be passing through Calcutta on his way home in March 1910.

1910 On 15 June 1910 John William Evans (1857-1930, President of the Geologists Association 1912-14, and the Geol. Soc. 1924-6) demonstrated a model of the 1906 earthquake at the Geological Society which emulated the classic elastic rebound model of Reid ( it is possible, though rather improbable, that Evans has not read the Larson report of the earthquake). He mentions Oldham's 1908 model as a starting point and characterises it as inadequate. Yet despite its remarkable ability to demonstrate the earthquake cycle, Oldham rejects Evans' model because he alleges it cannot replicate strains in the real Earth, or account for the rich specturm and energy of local and teleseismic waves. Oldham favors an "explosive" mechanism for earthquakes, a mechanism that most people did not subscribe to (and certainly do not now). Evans in his response strongly disagrees with Oldham indicating that he is "strongly opposed to the views of the school of seismologists, to which Mr. Oldham had, it seemed, now given his adherence, who thought that the great earthquakes represented explosions of igneous materials in the Earth's crust". Evans in his article (Q. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 66, 346-352, August 1910.) offers the following remarkable statement " the slow motion of the left frame represents a gradual creep of the bed of the Pacific to the north-west relatively (sic) to the North American continent, giving rise to a region of strain in the neighbourhood of the coastline, which increases until fracture occurs in the San Andreas Fault" ...and later "The gradual northward movement of the North Pacific relatively to the continents on either side must be accompanied by intense folding and thrusting in the neighbourhood of the Aleution Islands; and immediately to the south of these is one of the most active earthquake tracts of which we have any knowledge."

1911 Elected Fellow of the Royal Society of London. Oldham may have returned to Burma for the next three years? Heron's Obituary of Oldham (1937) indicates he undertook some consulting for Messrs. Steel Bros. and Coy. Ltd in the Burma Oil Fields during the winter months of an unspecified year. He may have been refering to the 1909/10 seson only. Steel Brothers were concerned about this time that their main oilfield was losing productivity and that new fields needed discovering. In the next ten years new fields were indeed found and it is quite possible that Oldham was involved with this search.

1912 He was Vice President of the Geological Society of London 1912 and 1913 and on the council, but is not recorded attending any meetings.

1913 From a 15August letter to Nature from his new address at 8 North Street, Horsham, Sussex, we find Oldham again in England now aged 55. His house on North Street was a ten minute walk to Horsham railway station from where he could catch a train directly to London. In 2007, the house, which was close to St. Marks Church, like most of the church, was found demolished and replaced by an insurance company . The 1870 spire of St. Marks remains. Oldham's walk along North Street to the station is now interrupted by a walkway over an underpass; "Having been away from home, I did not see Mr Holmes' letter on Radium....... on June 19." It is not clear how long or why he chose to live in Horsham apart from its obvious rail link to London. An event that must have effected him deeply this year was news of John Milne's unexpected death 31 July at the age of 63. Geological Magazine,' vol. 10, No. 594, pp. 532-536 (December, 1913).

1914 on 20 Feb it is announced in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society that he is retiring from the council of the Geological Society and also from being one of the four Vice Presidents.

1915 We lose sight of Oldham in 1915. He booked a passage to Bombay on the steamship Mongolia leaving 23 January 1915. Perhaps he went on to Burma again. Captain R. D. Oldham is found mentioned in the Kew War Office archives WO 374/51280 but it is inlikely nthat this was him.

1916 2 Feb 1916 Gives a lecture on the support of the Himalaya at the HQ of the Geol Soc in Burlington House. This is the year that Oldham donated his personal library to the Geological Society of London. These included 91 journal volumes: Publications of the Japanese Earthquake Committee in Foreign Languages, the Bulletins of the Imperial Earthquake Investigation Committee, and the Boll. della Soc. Sismologica Italiana, the Annual Reports of the Cape of Good Hope Geological Commission and a complete set of the publications of the Soc. de Speleologie, Paris. 39 Volumes of other books were "selected", plus 156 works - 45 rare Indian publications: 47 papers on earthquakes, 32 on Permian glaciation, 9 on Petrology, 7 on paleobotany, and 16 miscellaneous. Included also are seismograms of the North pacific and South American earthquakes of 16 Aug 1906, and an album of photographs of the Ghona Landslip of 1894, which had been described by Holland.

1917 16 Feb the QJGS library report mentions his donations of 1916. Oldham probably moved to a new house near Kew Gardens to live with his sister Dorothea before 1917, because he wrote letters from this address at about this time. He lived in the house until his sister died in 1928.

Letter dated 28 May 1917 1 Broomfield Road, Kew, Surrey (Horsham letterhead deleted) where he returns a paper by William George Fearnsides to Percy Fry Kendall. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/library/spcoll/handlists/052MS570Kendall.pdf. He was at this address until at least 1929, after which time he uses the Athenaeum Club, Pall Mall SW1 as a forwarding address.

The National Portrait Gallery Negative of Oldham was photographed by Walter Stoneman in 1917. At least three photos of Oldham from slightly different angles are known from these sittings.

1918 April 1918 Discussion on sand dunes at RGS. His "Seasonal variation in the earthquakes" is published in QJGS.

1919 On 12 March he read Pascoe's paper on the reorganization of Punjab and Ganges rivers to the Geological Society in London. Pascoe's article makes frequent (and generous) citations to Oldham's earlier contributions. Interestingly, unknown to Oldham or Pascoe at the time, Pascoe was destined subsequently to re-write Oldham's "Manual of the Geology of India', and to update his Indian bibliography. The first of Pascoe's three volume, third edition of the manual, was written in 1933 but could not be published because of the shortage of paper. The manual is a masterpiece, integrating the first two editions, adding new materials and bringing the science up-to date. Then catastrophically after correcting the proofs, WW2 caused the 19 tons of metal type print to be melted down. Pascoe died in 1949 not having seen anything in print and it was not until 1965 that the third and last volume limped off the presses. The printing quality compared to the first two vollumes is poor and the manual sadly neglected, replaced as it is , by Wadia's simplified manual. The fourth volume of Pascoe's epic was an Index, a rather important feature of this massive work, because the work treats the geology of India in stratigraphic order, thereby making it impossible for consultation in geographically-oriented studies without reading the entire 3000 pages. Pascoe's version of this vital Index was lost without trace, and the GSI realising that it was essential, developed another that was published in 1967, 34 years after starting writing the manual, and two decades after Pascoe's death.

1920 Oldham was appointed President of the Geological Society of London and again rejoined its council 1920-1922. He attended meetings Jan 21st, Feb. 25th, Mar.10 & 24th, April 21, & May 19. On June 9th he chaired a meeting in which Cargill Gilston Knott gives a talk indicating the propagation paths of seismic waves through the Earth and shows the core to be a fluid. On 23 June he announces plans for fiscal solvency of the Geol. Soc. by charging for the Quarterly Journal (10s for the year or 3s per issue). He chairs meetings Nov. 3rd 17th, Dec 1st, and 20th. He is elected to the council of the Royal Society 1920-21. Oldham attends the first meeting of the Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 10 April 1920. His correspondence in the Society's archives from Kew are not of much interest -in August "I wonder how you will find Cornwall. My only visits have been in Spring & it was always cold, it is extremely so here at present.", and in November "I also enclose a letter from Walker forwarded by Belafonte. He evidently means it as a piece of decency as it reads better in the German than in the translation. We shall have to consider what to do with it. I hope the letters to laTouche & the Copyist Board representatives have gone off. I am anxious to push on these areas of Lit. as fast as possible. "

1921 Oldham chairs 14 meetings of the Geological Society: Jan 5th &19th Feb. 2nd, 18th & 23rd. March 9th & 23rd, May 4th &25th, June 8th, Nov 9th &23rd, Dec 7th and 21st

1922 Chairs 4 meetings of the Geological Society: Jan 4 and 18, Feb. 1 & on Feb. 17th when he resigns and a new president (A.C. Seward) is elected. Oldham remains for a further two years as one of the four vice-presidents and one of the 23 members of the Council. At the 1922 meeting he gives a talk as retiring President, entitled "The cause and character of earthquakes" pages LV to LXVIII, Proc. Geol Soc. As vice president he continues to chair meetings March 8th where he comments on a paper, and again 6 Dec 1922. In 1922 he publishes his article on Gravity and geodesy of India and the Himalaya.

1923 He remains as Vice President on the council and publishes articles on earthquakes in the Pamirs and in Italy).

1924 15 Feb. 1924 it is announced in QJGS that he is retiring from serving on the council and as a vice president.

1925 Researches materials on the 1819 Rann of Kachchh earthquake. On 2 Dec 1925 he reads his article on the depth of earthquakes to Geological Society which considers intensity distributions and attempts to quantify accelerations.

1926 He publishes his report on the 1819 Kachchh earthquake, the predecessor to the 2001 Bhuj earthquake. He includes an update on the 1897 earthquake whose findings are curiously misplaced compared to his critical and abundant observations published in 1899. In Nature, however, he publishes something new - on the Loculus of Archimedes- a graphic tile game purportedly invented by the Greek mathematician. His sister Dorothea Margaret Oldham died 1 Nov 1926 leaving him £1063 5s 1d.

1927

1928 11 January 1928 he attends a Geological Society meeting and comments on an article on Oman. Middlemiss and Heron indicate that he spent summers in the south of France during the next several years, as suggested by the first of several articles on the Rhone starting in 1925. In fact his interest in the geology of the Rhone had started at least a quarter of a century earlier, as mentioned in a summary of the Cambridge British Association meeting in 1903 (Geog. J. 1904, 460). In 1928 following the death of his sister Dorothea, he gave up his house in Kew and used the elite Athaenium Club in Pall Mall as a forwarding address for his subscriptions to the RGS and the Royal Society.

1929 His first article on changes in level of the Rhone is "taken as read" 23 October 1929 and is published in the following year. His articles on the Rhone delta include quotes and reconstructions of maps written in Greek, Latin, French and German. He describes the implications of the old elevated gravel deposits that must have been formed when the Rhone was a much more aggressive river (photo above). He notes that sea level at the times of the Romans and in the 10th century must have several meters lower than at present to account for the sequential abandonment of ports now far inland on the westerly branch now know as the Little Rhone. St Gilles, (above) was abandoned first, then Aigues Mortes, a fortified walled town with a large lighthouse (see photo left below) to guide ships into its now absent harbour. The Little Rhone now debouches into the Mediterranean through a controlled channel at Le Grau du Roi. See photo right below.

1930 Middlemiss believes this may have been when Oldham last visited Hyeres in the south of France. Photo below is of the center of this medieval city. At about this time Middlemiss believes he spent his time between Llandrindod Wells and the south of France collecting mail from his forwarding address in the Athaenium, London.

1932 He was elected a Fellow of Imperial College in 1932. The Roman harbour works are several meters below the current banks of the Rhone in Arles (below).

1934 His last article is published on the history of the Rhone delta. This one summarizes his earlier work and mentions leveling data that support his conclusions of onging tectonics.

15 July 1936 He died in the Gwalia Hotel Landrindod Wells (see obituaries). It is not known what happened to the bronze Lyell Medal and the books, papers, and writings that were not selected to be archived by the Geological Society in 1916. Oldham's traveling life style of rentals and finally a hotel leads one to doubt whether there was anywhere he could have stored a large mass of writings after he abandoned his house in Kew. It is not at all clear that there were any close relatives who would have taken an interest in his remaining possessions. His youngest brother Henry Yule Oldham, ("a genial professor who published almost nothing" who had by then retired from Cambridge) outlived him by 15 years. He may have collected his possessions from Wales. When he himself died without ever having married, but his effects were transferred to Thomas Vicars Oldham, a medical practitioner.