Colorado Mineral Belt

Tectonics, Timing and Ages

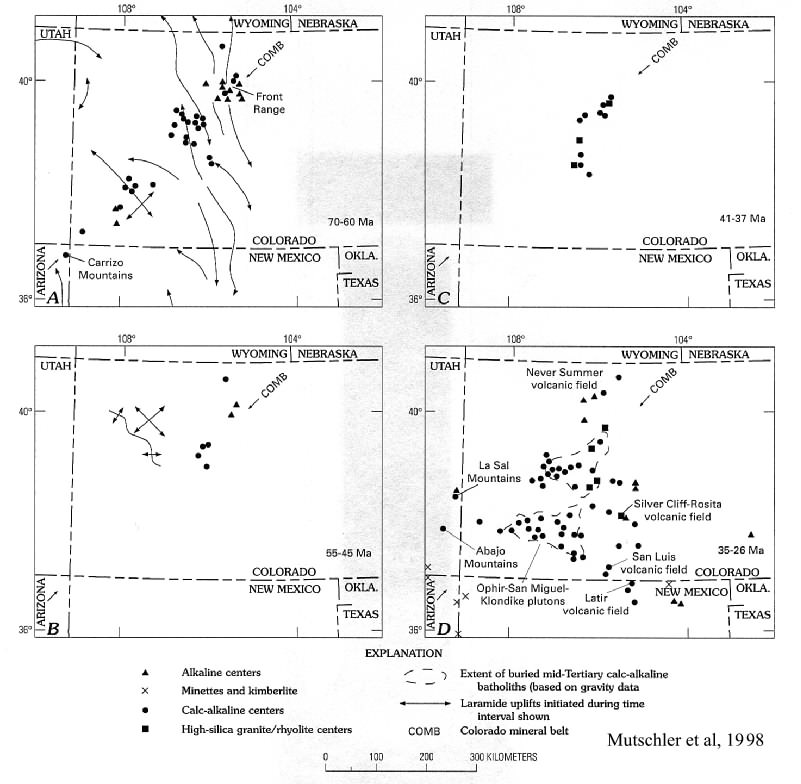

Igneous activity in and around the CMB has been broken down into three episodes:

1) Laramide (~75-42Ma)

Calc-alkaline (central CMB) and alkaline (ends of CMB) magmatism began just before an episode of regional compression related to the Laramide orogeny.

2) Middle Tertiary (~40-26Ma)

Calc-alkalic and high-silica rhyolite magmas coincided with regional extension followed by the middle Tertiary ignimbrite flareup.

3) Late Cenozoic (~25-0Ma)

Extension, rifting, and uplift occurred with bimodal magmatism.

(Mutschler et al, 1987; Stein and Crock, 1990; Cunningham et al, 1994)

Laramide igneous activity in the Colorado Mineral Belt has great geologic significance in that it began shortly after the start of the Laramide orogeny and offers clues to help resolve the debate over what was going on beneath and within the continental crust during the Laramide. Laramide magmatism also allows greater insight as to whether or not there was Laramide ‘flat slab’ subduction as far inland as the Colorado Rockies.

Laramide calc-alkaline (Eric Cannon) and alkaline (Eric Cannon) magmatism coincided with some of the highest Laramide uplift within the CMB. Such a co-occurrence suggests that either pre-existing deep crustal fractures facilitated emplacement of magma (possibly facilitating Laramide uplift as well), and/or that during the Laramide there was high lithospheric heat flow in this region (Mutschler et al, 1987). Geophysical anomalies suggest that there is increased heat flow today beneath the Rockies (Decker, 1988) compared to that of the Great Plains, which helps to support the idea that there may also have been local increased heat flow during the Laramide. The CMB also falls on the Colorado lineament, thought to be a remnant crustal weakness left behind by a Proterozoic shear zone (Cunningham et al, 1994; Karlstrom and Humphreys, 1998; Mutschler et al, 1998). Such a weakness would also help accommodate rising magma.

There are several hypotheses regarding where and why there was magma generated in the CMB. An important factor to consider, first, though, is when these magmas were brought to the surface. There still remains some uncertainty regarding whether or not there is any well defined age progression within the CMB.

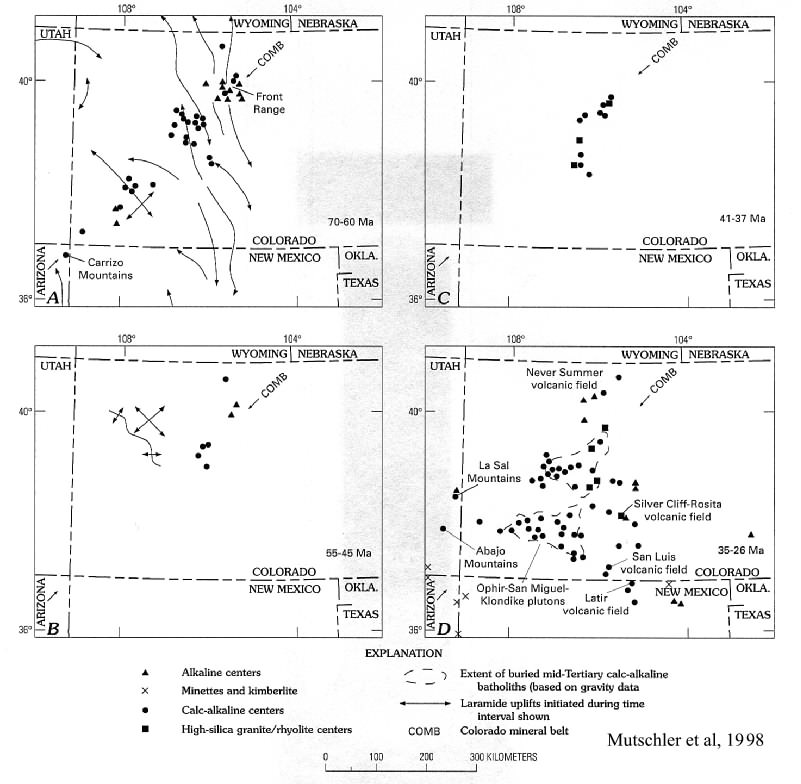

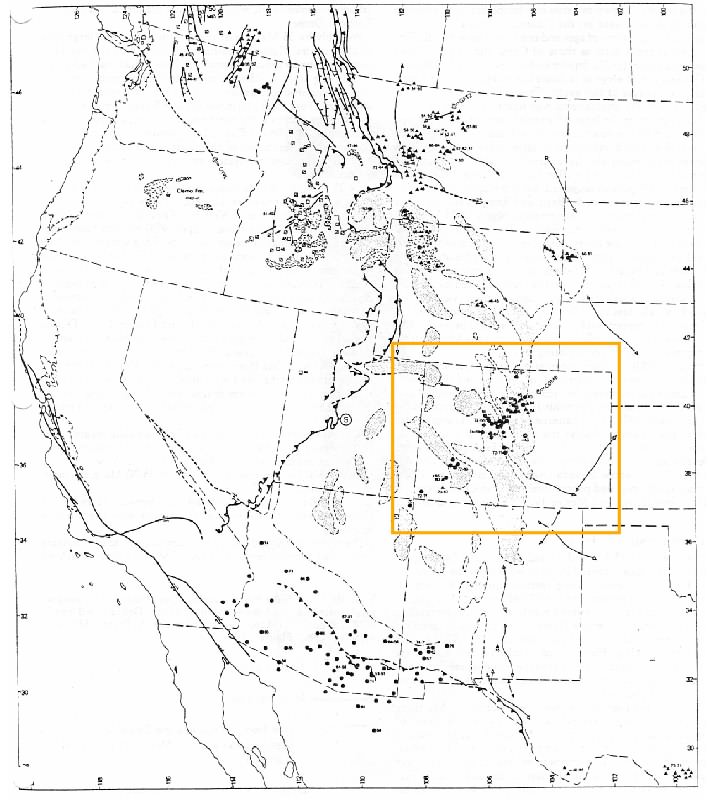

Magmatism within the CMB in general coincided with magmatic activity in parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho and Washington. Within the CMB, however, timing of individual occurrences of Laramide magmatism is difficult to constrain, due in part to overprinting by thermal and younger magmatic events throughout the CMB. Cunningham et al (1994) noted a general southwest to northeast age progression for Laramide igneous centers, but this age progression is only well constrained in the southwestern portion of the CMB. These authors also noted two northwestern trending groups of Laramide igneous rocks. In a later study, Mutschler et al (1998) argued that no clear age progression could be found within the CMB based on K-Ar dates on these rocks.

Location of Laramide igneous activity in the western U.S. Orange box shows approximate area of the next figure and of Laramide CMB magmatic activity.

(Figure from Mutschler et al, 1998)

Detail of CMB Laramide igneous activity and K-Ar ages. (From Mutschler et al, 1998)

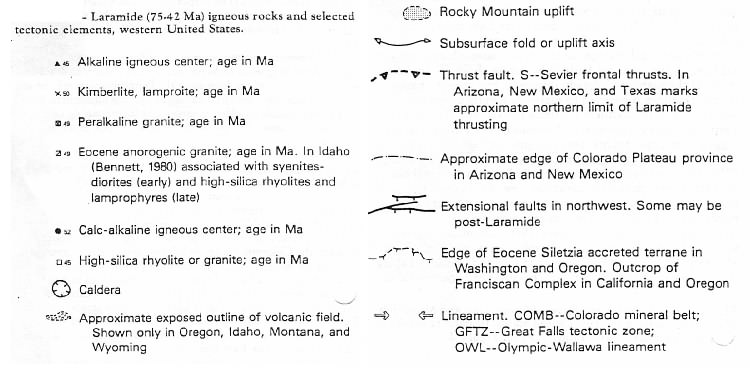

Key for figures from Mutschler et al, 1998

<-Back to the geography | Home | References | on to enter the petrogenesis debate->