What happens in the Arctic stays in the Arctic. Unfortunately not.

If the blanket of ice coating Earth’s northernmost seas were to melt, much of the northern hemisphere, if not the planet, would feel the aftershock. “Warming of the Arctic is not just an issue for the Arctic,” said Mark Serreze, director of the CIRES National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). “It’s an issue for all of us.”

The sea ice that stretches for more than 3 million square miles atop the Arctic Ocean works to keep life cool in the Arctic, as the icy cover reflects sunlight and stops the sun’s rays from heating up the ocean beneath. This ocean-cooling dynamic also means the Arctic sea ice acts as an air conditioner for the northern hemisphere, keeping the oceans and surrounding land masses chillier than they would be in its absence.

Remove some of that icy cover, however, and the sun’s rays can now warm the exposed water, creating a ripple effect throughout the northern seas. Due to its climatic importance, NSIDC scientists have tracked sea ice extent year-round since 1979. They also track the “sea ice minimum,” the lowest coverage or extent of the ice across the ocean each year.

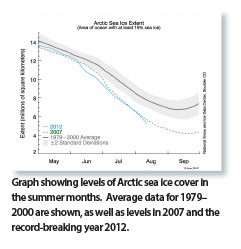

Just as the moon waxes and wanes, sea ice extent grows and shrinks each year with the seasons. In winter, colder temperatures build up the extent of the ice, and each summer brings partial melting of the coverage. Typically mid-September marks the end of the melt season when the sea ice cover is at its lowest. After that date, the sunlight is almost gone from the top of the world, and the ice cover begins to expand again.

In constant climatic conditions, scientists would expect to see little change in the coverage from one year to the next.

But that isn’t what they have seen.

The “not so slow” decline

“The first indications that Arctic sea ice was declining really came out in the late 1980s,” Serreze said. “We started to see this overall downward trend.”

Scientists at NSIDC were some of the first researchers to notice the decline, and they have since measured the ice retreating to record-low extents in late summer and becoming thinner year-round. Since 1979, Arctic sea ice extent has declined by more than 30 percent in summer months.

This rapid speed of decline has been helped along by a simple feedback mechanism. As the sea ice melts, the dark water absorbs much more heat than the white surface of the ice, warming up the ocean and the air above even more. Both effects cause more ice to melt. Scientists call this vicious circle “Arctic amplification.”

While scientists understood this mechanism, they were unsure at first as to what drove the initial ice decline. Was the sea ice responding to global climate change or just dipping because of unusual weather or ocean circulation patterns? “It wasn’t clear exactly what was happening,” Serreze said. “We were looking at what seemed to be an emerging trend, but we had a pretty short data record.”

During the time period when ice had started to decline, a natural weather pattern known as the Arctic Oscillation had been persisting in a phase that tends to favor low sea ice extent. And while other signs pointed to climate warming by the 1980s, researchers were not sure if Arctic sea ice was already responding to those changes.

It wasn’t until about 2001 that the answer started to become clear. At about that time, the Arctic Oscillation switched from a generally persistent positive phase into a more neutral phase. If the positive-phase Arctic Oscillation were driving Arctic sea ice decline, scientists would see the trend turn around. But, Serreze said, “The trends just got stronger if anything. And that was really one of the major things that convinced me that the sea ice was responding to global warming.”

Since then, Arctic ice extent hit a record low in 2005, and then broke that record by 23 percent only two years later, in 2007. That low was nearly matched in 2011.

The ice extent recorded for June 30, 2012, of 9.59 million square kilometers (3.7 million square miles) would not normally be expected until July 21, based on 1979–2000 averages. This puts extent decline three weeks ahead of schedule.

September 2012 could see a new record for the Arctic ice extent.

Beyond the Arctic

NSIDC scientists continue to monitor Arctic sea ice on a daily basis and make the data and analysis available for other researchers as well as the general public. While it now seems clear that the Arctic sea ice is responding to climate change, researchers have many more questions about how the Arctic will evolve.

Serreze and other researchers at NSIDC are also exploring how the declining sea ice will affect the climate itself. Serreze said, “If Earth’s climate warms, the Arctic warms more because of various feedback effects.” The feedbacks have already kicked in: Temperatures in the Arctic have risen substantially more than global temperatures in recent years.

Declining sea ice already impacts people who live in the Arctic and depend on the ice. With no protecting ice cover, shorelines are eroding, forcing entire towns to move, and longstanding patterns of travel and hunting have become disrupted and dangerous.

Changes in sea ice may also be affecting people who live far from the Arctic. Recently researchers have found links between extreme weather events in North America and declining Arctic sea ice cover. Recent studies suggest that having less ice in the fall, for example, could contribute to stronger winter storms in other parts of the northern hemisphere.

“What we are realizing is that the change in Arctic sea ice is not just a problem for the Arctic,” Serreze said.