The Day the Earth Moved

Probing the Japanese earthquake

By Jane Palmer

A mere three days after an earthquake so powerful it knocked the planet off its axis—the March 11 Honshu quake—CIRES Fellow Roger Bilham gazed from the safety of a helicopter at the flattened towns and flooded coastline of the Japanese island below.

Bilham, the first geologist outside Japan to conduct an aerial survey of the damage, had arrived in Japan to learn about the nature and impact of the earthquake and its accompanying tsunami. “The extent of the damage was truly amazing,” said Bilham, the scientific member of the NOVA team making the documentary Japan’s Killer Quake. “The tsunami picked up everything in its path—cars, houses, warehouses—and just tumbled them relentlessly inland on and on and on.”

Although power, fuel and food shortages made immediate access to the epicentral region difficult, seismometers had diligently recorded every ripple of the quake. GPS receivers also had pinpointed the island’s location as it shook, shuddered and ultimately shifted permanently by as much as 5 meters toward the east in response to the earth’s tremors. “Never before have we had such a surplus of data,” Bilham said. “There are no mysteries in this earthquake.”

Piecing together the cause of the quake didn’t prove difficult for scientists. Earth’s crust is made up of several colossal slabs of rock—known as tectonic plates (see p. 13)—and Japan lies on a boundary between two plates. Each year the Pacific plate had driven farther underneath

the edge of the North America plate that Japan sits on, compressing the edge and dragging downward the North America plate thereby causing immense stresses to build up. "The energy that drove this earthquake had been building up for many hundreds of years," Bilham said. "Think of it as a giant elastic band that has been wound up for a thousand years."

At 2:45 a.m. March 11, 2011, the tension reached a breaking point. At a location 100 kilometers off the coast of Japan, the edge of the compressed plate finally sprung eastward tens of meters, initiating a magnitude 9.0 earthquake.

Shock waves radiated outwards through Earth, and Japan’s detection systems picked them up instantly. The billions Japan had invested in early-warning sys- tems and earthquake engineering paid off as a combi- nation of old and new technologies—including sirens and email messages—alerted the citizens and kept most of the cities’ structures standing, Bilham said. “My first reaction on arrival in Tokyo was of admiration for the seismologists and earthquake-engineering commu- nity of Japan,” he said. “It was a success story given the enormity of the earthquake.”

And then the tsunami struck.

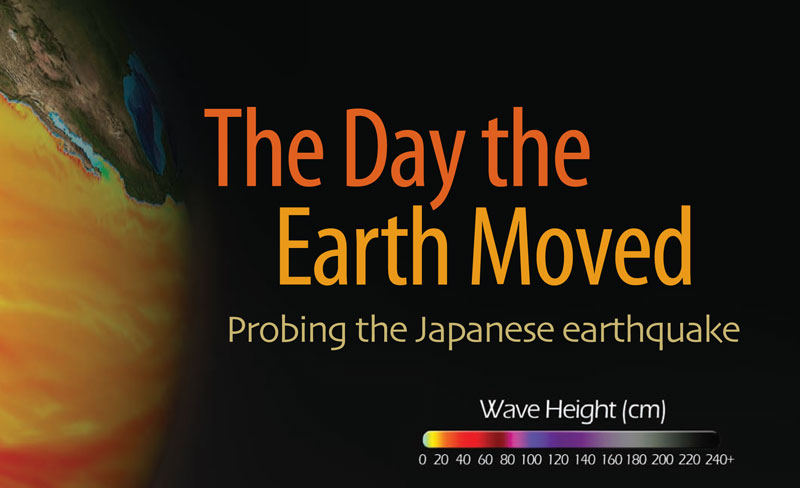

The sudden upper flip of the compressed rock lifted a six-kilometer mass of water upward to the surface of the sea. As this same rock collapsed back, it propelled immense waves across the ocean.

One side of the wave raced toward the coast of Japan. As the speed of an ocean wave depends on the water depth (a wave will travel slower in shallow water), in the deep ocean the tsunami travelled at more than 800 kilometers per hour—as fast as a jet aircraft. It took just minutes to reach the coast, and it raced ashore with heights of 13 meters in places. "Probably a cubic kilometer of water just sploshed landward and kept going until it ran out of steam," Bilham said.

Despite a death toll in the tens of thousands and a

recovery cost estimated to exceed $300 billion, worse may still be to come. For decades, Japanese scientists have anticipated a large earthquake to hit from the south, caused by a slip of the Philippine plate relative to the Eurasian plate. And sometimes a great earth- quake, like the Honshu quake, can cause the next patch of the plate boundary to slip, Bilham said. Con- sequently, all eyes are on how the Honshu earthquake has impacted the neighboring part of the plate bound- ary, he said.

"This whole region is in a very high state of stress, and seismologists have been expecting it to go any min- ute—so this recent earthquake is going to have brought that closer in time," Bilham said. "The question is: how much closer?"