How Risky is the Rift?

Estimating earthquake potential of the Rio Grande Rift

By Jane Palmer

While the impacts of the August 23, 2011, Colorado earthquake at magnitude 5.3 paled in comparison with those of the magnitude 5.8 earthquake that hit the East Coast the same day, it showed the Rio Grande Rift—the north-trending continental rift zone that extends from Colorado's central Rocky Mountains to Mexico—is by no means dead but seismically alive and kicking.

"We don't expect to see a lot of earthquakes in that region, or big ones, but we will have some earthquakes," said Anne Sheehan, CIRES Fellow and Associate Director of CIRES Solid Earth Sciences Division. Sheehan, her team and colleagues from the University of New Mexico, have studied the rift zone—the chasm where Earth's crust is being pulled apart—for the last five years to assess the risk of earthquakes.

Colorado and New Mexico, with their mix of mountains and plains, sit mainly on the seismically stable part of the nation where earthquakes are a rarity. The Rio Grand Rift region; however, presents an exception to this relative calm. Along the rift, spreading motion in the crust has led to the rise of magma, the molten rock material under Earth's crust, to the surface, and the creation of long, fault-bounded basins that are susceptible to earthquakes.

Previously, geologists have estimated the rift is not spreading at all, or has spread apart by up to 5 millimeters each year, but accurate measurements have proved problematic, Sheehan said. The slow rates of motion in the region mean that any instruments must be able to measure mere fractions of

millimeters of movement, she said. "Low-strain-rate regions have been notoriously difficult to get a real number for," Sheehan said. "The margins of error in previous estimates can be nearly as much as the estimates themselves."

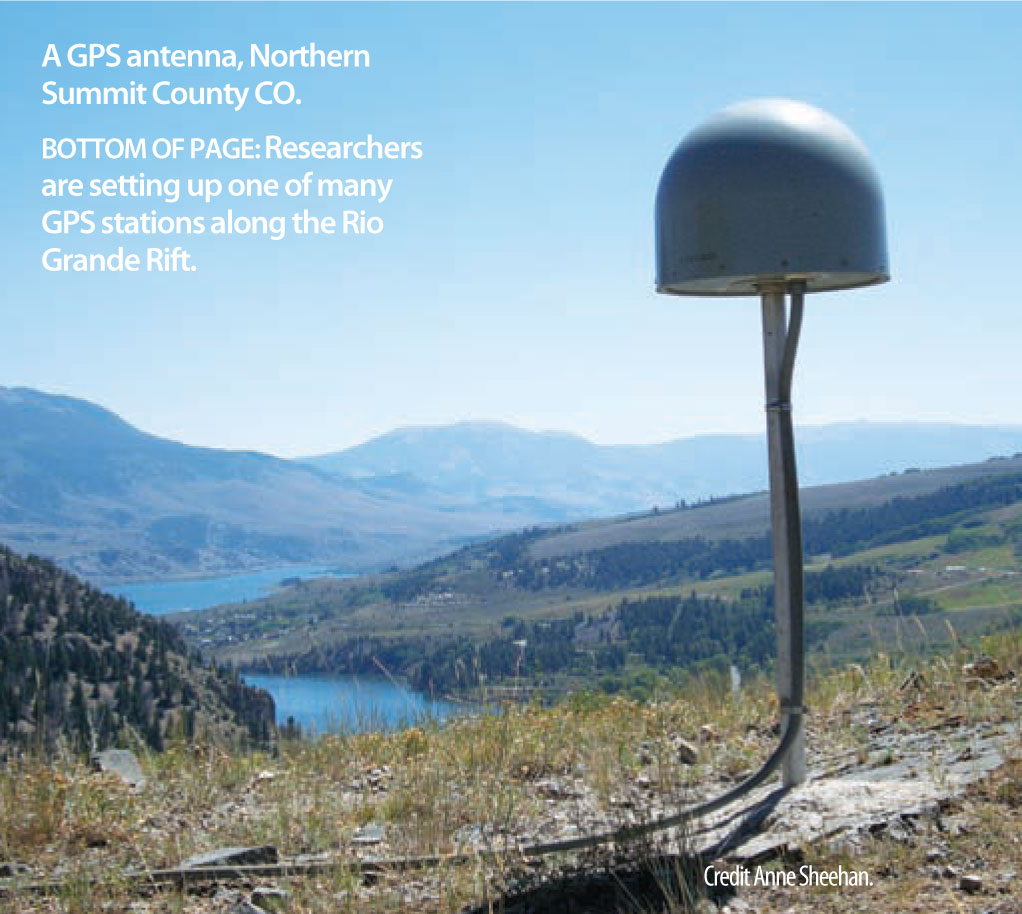

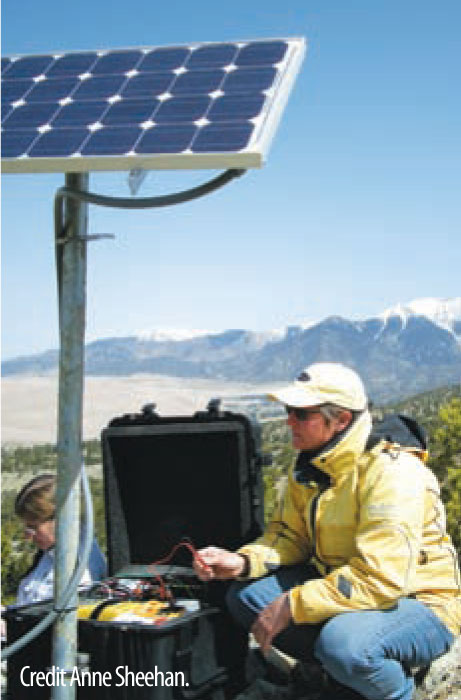

To address this problem, the scientists installed semi-permanent Global Positioning System (GPS) instruments at 25 sites in Colorado and New Mexico to track the rift's miniscule movements from 2006 to 2011. "The GPS has reduced the uncertainty dramatically," she said. "We can actually resolve those tiny, tiny motions—I think it is amazing that it works."

The primary goal of the researchers was to assess the potential earthquake hazards posed by the rift and to better understand how the interiors of continents deform. The high-precision instrumentation has provided unprecedented data about the volcanic activity in the region—information that will help give probabilities for the likelihood of earthquakes, Sheehan said. "The big questions we wanted to get at were 'Is the rift active? How is it deforming? Is it alive or dead? Is it opening or not?'" she said.

The researchers also hope that the data will shed light on the mystery of how continents deform away from plate boundaries, Sheehan said. At plate boundaries scientists can observe what is going on pretty clearly, she said. "Things move past each other and crash into each other—at active plate boundaries the rates of motion detected by GPS can be centimeters per year," she said. "Compare that with the fraction of a millimeter per year that we have measured for the Rio Grande Rift."

The scientists will publish the study's results in the scientific journal Geology in early 2012. Until then, Sheehan cannot talk about the details of their findings; however, she will say what the recent earthquake has shown so conclusively: "The rift is definitely still active."

The Science

"The big questions we wanted to get at were 'Is the rift active? How is it deforming? Is it alive or dead? Is it opening or not?'"