Monsoon Mystery

Investigating the forces that drive the Indian Monsoon

"There's a big controversy about whether the Tibetan Plateau is important or not in driving the Indian Monsoon."

The Himalaya strengthens the monsoon in another way: They prevent India's warm, moist air from mixing with the cold, dry air from China and Europe. "Without that barrier, everything would dissipate away, and you'd get rain but not a strong monsoon. So even with no Tibetan Plateau, you should still get monsoons."

Nevertheless, even if the Himalayan/southern edge barrier is the dominant player—mechanically strengthening the monsoon—that doesn't mean the plateau has no effect. It could still act as a "thermal pump," intensifying the monsoon to some degree, which is what Molnar is investigating. "I'd like to know whether Tibet's thermal effect matters or if it's purely mechanical." To answer that, he's looking at the plateau's geologic history (when and how it became high) and the area's climate history (when the monsoon was strong and weak), to see whether one affects the other.

But don't write off the Tibetan Plateau yet. Even if it turns out to have a minor role, that could spell the difference between a strong and weak monsoon. A strong monsoon is defined as 10 percent more rain than average and a weak monsoon as 10 percent less. "That's a small range, but as far as Indian civilization is concerned, if you dropped its rainfall by 10 percent, it would be a different world," Molnar said. "So the Tibetan Plateau doesn't have to make a big contribution to have a big effect."

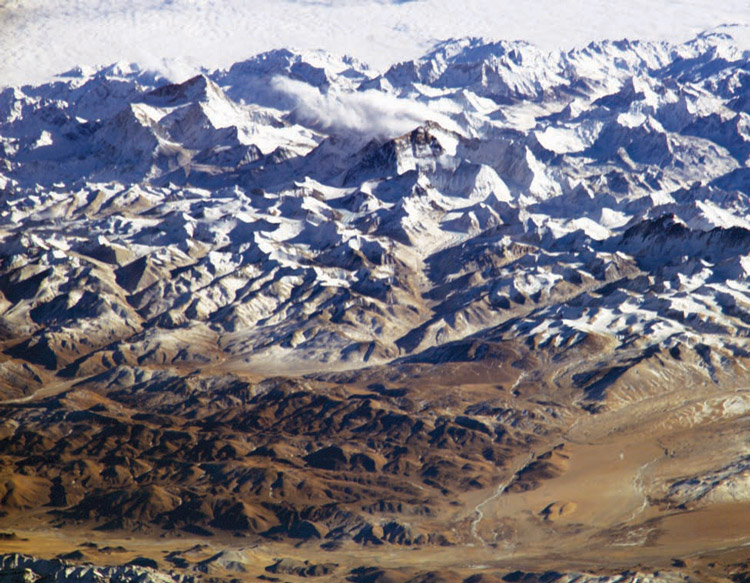

The Tibetan Plateau, the "roof of the world," was thought to help fuel this process by further heating the air and driving atmospheric convection (rapid ascent of warm, moist air). "The sun warms the plateau's surface, making air at that altitude hotter than it would be without the plateau," Molnar said. Consequently—under the traditional theory—the high, hot plateau acts sort of like an air pump, creating a low-pressure zone that sucks in moist, rain-bearing air from the Bay of Bengal.

But some of Molnar's colleagues noticed something strange. The hottest summer temperatures in the upper troposphere (about 10 kilometer high) weren't over the entire Tibetan Plateau, as you'd expect, but over its southern edge and the northern Himalaya. Most of the Tibetan Plateau wasn't playing much of a part.

"What this means is that the high temperature was due more to latent heating [heat released when water condenses]," Molnar said. Essentially, the Himalaya forces up moist air from the ocean, he said. As the air rises, it cools and water condenses, releasing rain and latent heat. The latent heat makes the air hotter, which makes it rise higher to the top of the troposphere (bottom of the stratosphere). This cycle continues, leading to the high temperature seen aloft over the southern edge. "So the monsoon rains are being driven not so much by the plateau, but simply because you have a wall of mountains mechanically forcing the air up," Molnar said.

By Kristin Bjornsen

Getting demoted from Batman to the Boy Wonder, Robin, isn't fun, but that may be the ignoble fate that awaits the Tibetan Plateau. For decades, meteorologists and geologists have thought the 5,000-meter-high plateau—the world's highest and largest—played a crucial role in the South Asian Monsoon (aka Indian Monsoon), but new research might relegate it to sidekick status.

"There's a big controversy about whether the Tibetan Plateau is important or not in driving the Indian Monsoon," CIRES Fellow Peter Molnar said. The classic view is that the plateau has a large part in strengthening the monsoon, while the new view gives it a smaller, mostly mechanical role. "We're trying to figure out what its role is," he said.

It's not an academic question since millions of people depend on the Indian monsoon, which can deliver more than 400 inches of rain to regions, for drinking water, hydropower and agriculture. Understanding the mechanisms behind it is key to predicting its intensity and fluctuations year to year.

From the Arabic word mausim for "seasons," monsoons are marked by seasonally reversing wind systems. From about June to September, the sun bakes the land in India; air heats up and rises, creating a low-pressure area. Wind rushes in from the southwest, carrying water from the Indian Ocean. In October, the land cools and the winds reverse, blowing back toward the ocean to the southwest.