|

The full John Muir Trail, including the descent to Whitney Portal, is 220.8 miles. Despite starting well south of Happy Isles (we came in about mile 40 of the trail), we almost went as far. We missed out on the gruesome 9800' climb out of Yosemite Valley to Donahue Pass, a climb that is an excellent argument for going south to north. Those through-hikers though missed out on the 3000' of uphill to Cottonwood Pass, so Megan was only 7,000' shy of the ~48,000' of vertical climb pure JMT hikers do. [Something is fishy in the math: Add to Megan's 41,260' the 9800' to Donahue but then subtract the 2400' we gained to hit the Muir Trail and the 3200' we did to leave from Crabtree and you get 45,460', not 48,000', so maybe Megan was really only 4200' shy of a full Muir Trail experience].

What did llamas gain us, and what did we lose? Certainly one thing we gained was the ability to drop some resupplies. Most (but not all) JMT hikers will resupply at some of Tuolumne Meadows (before we came on the trail), at Reds Meadow, at Vermilion Valley Resort, at the Muir Trail Ranch, and somehow over Kearsarge Pass (a few will drop down to Roads End near Cedar Grove). [One wonders a bit about the resupply for the group in Mile, Mile and a Half at Kearsarge; they make a big deal of the Tuolumne, Reds Meadow and Muir Trail Ranch supplies but only a brief oblique mention of getting a resupply at Kearsarge--this is actually buried in their online journal; they had planned on leaving a cache at Charlotte Lake--which is against the rules, by the ways--but failed to get it in, so had a packer meet them on the trail. Guess that wasn't as photogenic or exciting as the other caches (Note that their journal confuses Florence Lake, where they dropped their MTR resupply, with Lake Edison, which they never saw)]. We only needed the one at Muir Trail Ranch, so we avoided 2 or 3 other resupplies. This made things logistically easier, especially at Kearsarge Pass, where you either have to go out to the trailhead or arrange a food drop from a packer. Also our bear box was a much more convenient shape--I could put a big plastic bottle with Megan's preferred peanut-butter filled pretzels in one; in the usual bear cylinders these would have gone to mush quickly. I brought bread and peanut butter and jelly, not to mention summer sausage, green pepper, onion, cheese and tortillas, all heavier than what some would think wise. We probably had more clothes than most others, and we certainly had more books. We gained trail speed: going uphill we were never passed, maintaining a pretty steady 2.5 mph. We were often a bit slower going down than some hikers, but overall when we were on the trail, we'd pass more than be passed. And carrying only a daypack, in essence, meant that we were fresher on the trail and had more energy to consider taking pictures or wandering a bit. We had more time in camp; our average of basically 10 miles a day is pretty comparable to most JMT hikers. We could have taken more time in some places than we did--and we did use this to some advantage in stopping at 1000 Island Lake, for example. Many JMT hikers are slaves to their stomachs and resupplies and so have to make the miles each day. We could have added or lost a day somewhere (indeed we did) without a major complication. My greatest regret on this trip is that I didn't take the chance (or make the chance) to do more little side trips of discovery. My time was essentially all on the trail or in camp.

What we lost was some flexibility. Not every campsite works for llamas, and in large areas regulations prevented us from stopping. The worst was Rae Lakes, but the day we camped at Upper Crabtree Meadow (with the ranger's guidance) the Park Service closed that meadow to grazing (August 11). I am not sure what all the horse packers and any llama parties were supposed to do then. The ranger invited us to use Guitar Lake's meadow, but the official map for 2016 shows that as closed to grazing (though the text of the grazing regulations were confused), so presumably they would have to go north to Sandy Meadow. So we could not stop at Rae Lakes, for instance, and had we needed a resupply over Kearsarge we would have had to camp below Charlotte Lake. Similarly there are places you are not allowed to travel at all with llamas, so lesser used trails are essentially off limits in the parks.

Although we had more time in camp, we had more camp chores. Llamas need to be unloaded, unsaddled, put out to graze and watered. In the morning it took longer to pack the llamas than a backpack. Some places this wasn't too onerous (McClure Meadow and Upper Crabtree come to mind), but others' grasses were more sparse and so we had to move the llamas around a fair bit. With the warning that a llama could go from healthy to poisoned in under an hour, wandering off from camp for dayhikes wasn't in the cards much (though the reality was that we were so late into camp most days that there really wasn't time anyways).

There were things that could have been done better. For starters, making a list of what fits in balanced panniers is much easier than trying to remember by rote or figuring things out anew every day. I tried photos and that was no good, and it took too long to realize I needed a list. We started with trash going loose in a big bag--bad mistake, as the bag quickly became impossible to put in the bear box. A shift to using ziploc bags worked much better even though it took several by trip's end to hold all the trash. Having a sense of where good campsites for parties with llamas would have made things a bit easier. It was hard to guess if there would be enough grass near Rosalie Lake, for instance, or the lakes just after it. In some other case, there were places we maybe could have reached had we known they might be a lot nicer. I think I might take Lake Virginia over Purple Lake and Marie Lake over Sallie Keyes. We didn't have a windbreak for our small stove, so we were moving rocks around a few times. Bringing a few spices to use with FD veggies would have been a good idea. Using the extra ability to carry weight a bit smarter would have been welcome. We had several heavy books (a few never opened) and so didn't have a chair, for instance. I had serious raingear that weighed quite a bit; a lighter poncho would have been quite enough. A spare stove might have been wise--our stove was so small and light that it would have been trivial to have another, and a couple of times having two would have sped us through dinner. We were caught a little off guard on our resupply, which was not in the middle of the trip but on day 10, and so we had a few days where things didn't all fit in the bear boxes (though part of that was the unexpected gift of apple juice boxes). It is tons easier to decide you have to go on to another campsite when you aren't at the end of the day; earlier starts would have made some days a little easier. But we did make the whole trip and the llamas came through just fine (if there was any question, the 15 mile penultimate day answered that).

Some things worked really well. Although our gravity feed water filter died on the last day, choking on the stuff in Chicken Springs Lake, it worked beautifully for three weeks. (Since accidentally choking a filter like this is a possibility, taking a spare filter--which we had--and an alternative means of purifying water is a wise idea). The YB3 tracking device was useful when we suddenly were thinking we were a day ahead and then essential when fire broke out at our exit point. And even with it transmitting our location every halfhour while we were hiking and all the messages sent about the fire, it still had plenty of juice at the end (and was never recharged). Great device. What seemed a luxury proved more useful than expected: I had a tripod which allowed us to get our gravity feed water system hung up above treeline. And the straps that help connect llamas can be useful in hanging the water bag or a shower. The Muir Trail book by Wenk is a very useful resource--I had it where I could grab it at any moment, and I used it several times a day from wondering what trees we might be passing through to deciding if a possible campsite ahead might work out. The GoalZero solar panel setup was great--we strapped it on the back on one llama. We never came close to exhausting our power reserves. Having our water sandals in exterior pockets on the panniers worked well--shifting in and out for water crossings wasn't much of an issue (of course, Megan did more than me as she led the llamas).

There were some surprises along the way. Most backpackers (meaning about 95% or more) have no idea how to behave when encountering stock. You move downhill well off the trail for horses and mules. No doubt the horse packers will tell you tales of inconsiderate hikers. I think we encountered maybe 5 people who knew they should be on the downhill side or that they should ask; of the hundreds of others, nearly all were on the uphill side and right by the trail. Most folks have no idea whether llamas behave the same as horses and mules, and fortunately the answer is they don't--it is no big deal if you are standing by the trail as they go by. The exception is if you have dogs, and I will say that dog owners recognized that they needed to keep their dogs on leash and away from us (basically the llamas might decide they need to face the dogs as they pass, which becomes a mess with a string of llamas).

Another surprise were the sheer number of hikers doing the Muir Trail or even the PCT (though the PCT hikers we met were only doing part--the ones trying for the whole thing this year had passed through long before). This is reflected in the massive increase in permits issued by Yosemite for hikers heading out over Donahue Pass. It was simply amazing how many folks we encountered, and traditionally you see a lot fewer going north to south. Equally remarkable was the composition of the hiking community. When I was in my 20s and backpacking a lot, nearly everybody else was in their 20s or maybe 30s. Today, while probably a majority are in that age range, over a third of the backpackers looked to be in their 50s or 60s or maybe even their 70s. Backpacking! It made me feel pretty feeble, using llamas to carry the heavy load rather than my own back. Also a surprise were the occasional foreign visitors, those from Asia standing out with a very limited English vocabulary. There weren't many, but it seemed pretty brave to come to the U.S. and then engage in traveling our wilderness with its myriad traditions and regulations. The increased pressure was also evident in the number of backpackers we encountered who entered at Horseshoe Meadow (which was reflected in the unavailability of permits from that trailhead). It probably won't be long before additional limits are set (e.g., Yosemite could limit exits at Happy Isles, the Forest Service might have to limit entries over Trail Pass if that starts to see heavy use). Something that wasn't obvious at the start is that if you get a Forest Service permit and want to exit at Whitney Portal, you have to worry about the exit quota. (Climbing Whitney as Megan did requires an extra fee). You don't if your permit is from Yosemite or Sequoia/Kings Canyon.

Talking with the rangers (and I chatted with every ranger along the way), you get the impression that backcountry travel has focused onto the Muir Trail, leaving most of the backcountry emptier. The 1970s were the glory days in some regards for backcountry use in the Sierra; the heaviest use in Yosemite remains the mid-1970s when overnight stays in the backcountry exceeded 200,000 (more recently, numbers are in the 150,000-175,000 range). This heavy use led to the institution of wilderness permits and quotas (Kings Canyon instituted quotas in 1977, for instance, surprising my group on my first backpacking trip). Backpacking dropped off precipitously in the 1980s as the baby boomers moved on to jobs and families. Numbers slowly ratcheted back up in the 1990s before booming in the past decade or so. But it seems like the style of use changed. In the 1970s, hikers went everywhere; in the 2010s it seems like everybody is on the Muir Trail or the PCT. When I was on part of the Muir Trail around 1980, it didn't seem too crowded. The bigger concern then was taking out your trash--trash piles left by campers in the 50s and 60s were still evident. I remember camping at the Woods Creek Junction and it was pleasant enough, a nice site under the trees. Passing through on this trip, that same junction now is a major campground with sites pounded down up and down from the crossing. The use along the Muir Trail is heavy and apparently very heavy when the PCT through-hikers pass through, but the rangers indicate it is pretty light away from that trail. In a way this is echoing the long standing usage in Grand Canyon where the trails in and out of Phantom Ranch are freeways and other trails are rarely visited. Yosemite National Park might want to reconsider their plans on downsizing the High Sierra camps; right now those are magnets for pulling people off the Muir Trail or PCT (well, except the two on the Muir Trail).

Probably of interest only to me is how our accidental omission of a hiking day interacted with our response to the fire at Horseshoe. Had I corrected myself and had us stop on day 16 (Aug 7) at Twin Lakes, we would have been leaving Vidette Meadow on the day that Horseshoe closed. When would we have learned about this? Had we somehow found out before crossing Forester, would we have turned back? After all, that would have been 10 August and going forward at that point would have committed us to going out Horseshoe, or abandoning climbing Whitney, or running out of food. The Tyndall ranger had been planning to head off from his post on the 10th; I don't know if he ended up staying and heading down the trail to warn people. If he had, and had we met him at Forester as we did on the 9th, it is easy to imagine him encouraging us to head back to go out over Kearsarge Pass. [Actually, it is kind of odd that he hadn't yet heard of the fire when we met him on the 9th, especially in the evening]. Of course, had he not been on the trail, we very well might have learned of the closure only when we made it to Tyndall Creek. What would we have done on the 11th? It was only early afternoon when Greg got permission to pick us up at Horseshoe. If we had gone forward, we would have risked turning right back around, because exiting on the 14th over Kearsarge would demand a return upon reaching Crabtree. Had we waited at Tyndall we might have had trouble making Crabtree. Had we started back, we would have been committed to coming out Onion Valley. It would have been a very tense morning at the least. So, ironically, by screwing up and blowing past our short day on the 7th, we made the rest of the trip far more relaxing than we could have known.

The Horseshoe fire closures ended a couple of days after we came out (15 August). Greg knew one of the people who saw the fire start on 9 August--it apparently started on the south side of the road and blew across the road in a few minutes. So the fire was right at the road from the start. As I had surmised when I heard of the fire, it is thought to be human-caused. It is even possible that we met the people who started it as it almost certainly was an illegal campfire (Inyo had banned all fires). The Forest Service was allowing people with permits starting in Horseshoe to go through another trailhead (so the group Greg would have been dropping off on the 13th originally had to change plans; he was dropping them off on the 14th at Onion Valley). It was an unusual situation and one Greg said he had not encountered before (nor had I, for that matter).

Summary of our trip in table form. Long ago the old Wilderness Press quadrangle guides would list distances with "equivalent miles", which were miles plus a mile for every 500' of elevation gain. While this isn't entirely fair for us with the llamas, it might give a little better idea of just where things were tougher. Blue shading are low values, orange high values (ignoring the last day, and I added shading for next-to-last in categories where the Whitney climb was the low day).

| Day | Miles | Equivalent miles |

Camp Elevation | Net elevation | Total Uphill | Airline distance | iPhone Distance | iPhone Flights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.5 |

9.7 | 9,200 |

2000 |

2100 |

3.12 | 6.5 | 66 |

| 2 | 5.8 |

7.8 | 9,840 |

640 |

1000 |

2.29 | 7.0 | 83 |

| 3 | 8.9 |

11.8 | 9,350 |

-490 |

1470 |

4.27 | 8.5 | 92 |

| 4 | 12.0 |

15.7 | 8,690 |

-660 |

1850 |

7.73 | 12.7 | 46 |

| 5 | 10.5 |

14.5 | 9,970 |

1280 |

2000 |

7.18 | 12.6 | 72 |

| 6 | 7.6 |

10.9 | 10,290 |

320 |

1670 |

4.02 | 8.2 | 60 |

| 7 | 8.3 |

9.6 | 7,900 |

-2390 |

630 |

4.47 | 9.1 | 42 |

| 8 | 9.8 |

15.2 | 9,570 |

1670 |

2680 |

6.42 | 10.8 | 60 |

| 9 | 5.1 |

7.8 | 10,200 |

630 |

1330 |

3.94 | 6.0 | 59 |

| 10 | 7.2 |

8.1 | 7,840 |

-2360 |

440 |

3.51 | 7.7 | 29 |

| 11 | 9.6 |

13.4 | 9,640 |

1800 |

1880 |

7.42 | 10.6 | 31 |

| 12 | 9.6 |

13.2 | 11,440 |

1800 |

1800 |

5.41 | 9.6 | 123 |

| 13 | 10.6 |

11.7 | 8,340 |

-3100 |

550 |

5.80 | 11.4 | 21 |

| 14 | 9.9 |

16.2 | 10,670 |

2330 |

3140 |

6.74 | 11.5 | 111 |

| 15 | 10.2 |

14.9 | 10,990 |

320 |

2350 |

7.18 | 11.1 | 96 |

| 16 | 12.5 |

15.8 | 9,470 |

-1520 |

1630 |

7.29 | 14.5 | 77 |

| 17 | 11.6 |

17.5 | 9,870 |

400 |

2970 |

7.00 | 14.0 | 101 |

| 18 | 11.9 |

18.4 | 10,920 |

1050 |

3250 |

7.69 | 12.0 | 71 |

| 19 | 11.8 |

16.6 | 11,580 |

660 |

2400 |

6.25 | 13.0 | 131 |

| 20* | 3.2 |

3.2 | 10,450 |

-1140 |

0 |

2.26 | 3.9 | 5 |

| 21 | 14.9 |

21.0 | 11,250 |

800 |

3050 |

9.95 | 17.2 | 119 |

| 22 | 4.7 |

5.0 | 10,040 |

-1210 |

150 |

3.58 | 5.8 | 2 |

| Average | 9.1 |

12.6 |

9890 |

130 |

1740 |

106.2 airline |

*: Megan climbed Whitney, so not easy for her. Adding in her 9.6 miles and 2900' elevation gain would increase the average to 9.6 miles/day and 1870' of average elevation gain. Put those in and the blue colors go away on day 20.

Total for the trip: 201.2 miles traveled (210.8 for Megan), 38,340' total elevation gain (41,260' Megan).

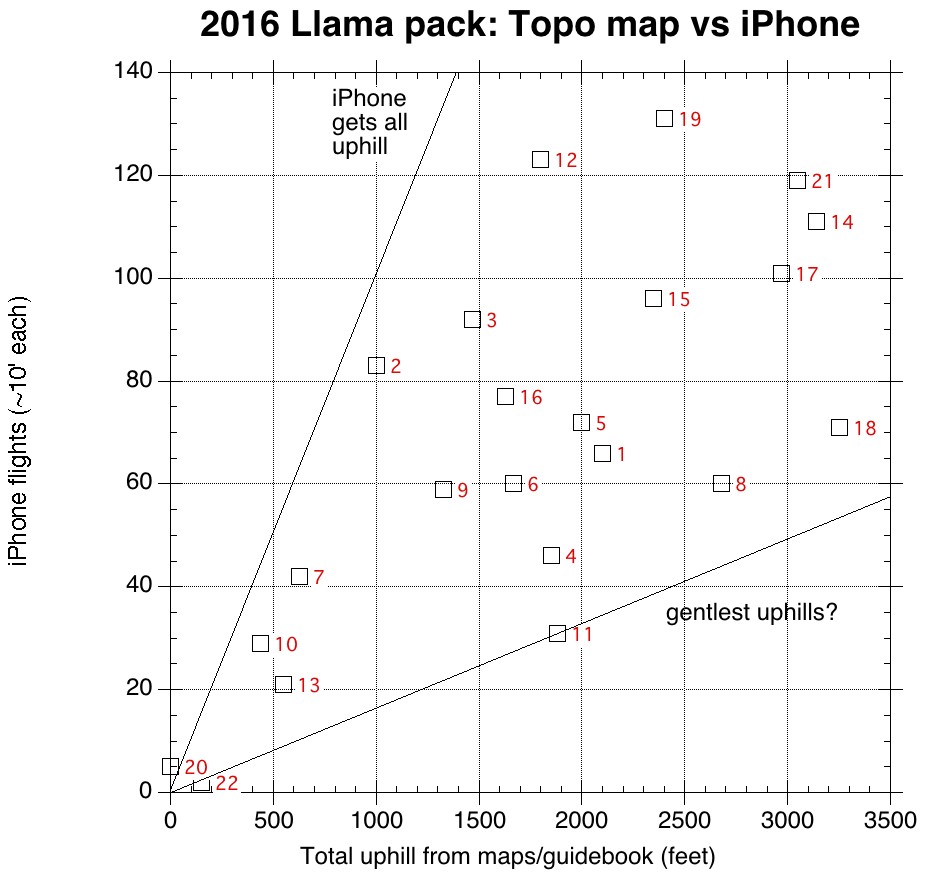

So some fun with plots (or, just what does that iPhone tell you, anyways?)

Consider the first plot, above. iPhones use an internal barometer to gauge uphill, so presumably in order to separate out changes in barometric pressure the iPhone only captures steep uphill climbs. The measurement are flights of stairs, each supposedly about 10' high, so the lefthand line should get points where the uphill is all pretty steep, while days where the iPhone only captured a fraction of the uphill are presumably gentler. So of the four biggest uphill days, day 18 (the crossing of Forester Pass) was the gentlest, which agrees with my impression. Our penultimate day, with the climb over Guyot Pass (which was gentle) and up to Chicken Springs Lake (which was not) had the steepest pitches. Surprising (to me) is that the overall gentlest grades were on the climb into Evolution Valley, where only the switchbacks from the San Joaquin to the mouth of the valley seemed to register on the iPhone.

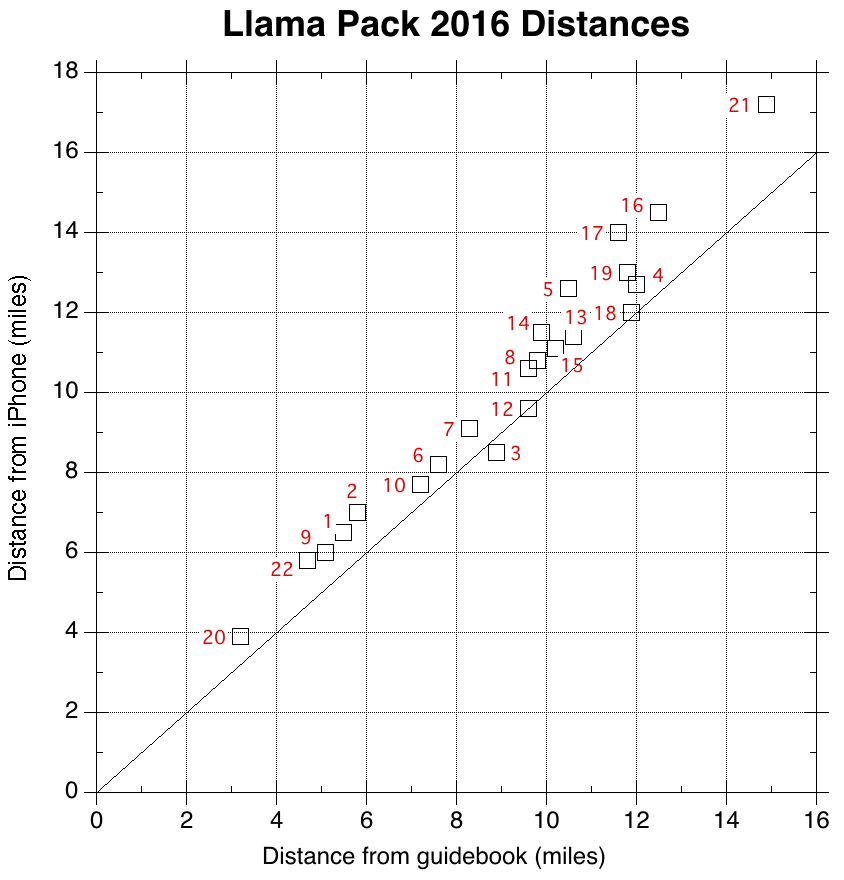

The iPhone is also measuring distance walking or running, apparantly from the GPS chip. You expect the iPhone distances to be a bit greater than the distances in the guidebook along the trail for a number of reasons: there is some walking around off the trail (taking pictures, eating lunch, finding campsites), the trail distances might be missing some of the wiggles on the ground, and the iPhone might overestimate distances because of the uncertainty in the GPS locations along the way. A best-fit line to these measurements yields 0.23 miles + 1.086 * guidebook distance; the average difference in distance is 1 mile. If the quarter mile represents time spent in and around camp, then the 8.6% higher distance would be some combination of iPhone error, guidebook error and wandering while hiking; alternatively closer to a mile of walking was spent on diversions and the on-trail hiking was about correct. While day 3's guidebook distance might be off because of the lengthy off-trail hike from the campsite, that days 12 and 18 are right on suggests the error is more likely on the iPhone than the guidebook. (Day 21 was not from the guidebook and so could be seriously underestimated). A more thorough analysis elsewhere indicates that the iPhone was in error. In doing that, though, I found that the trail was most winding on day 3 and straightest on day 11.

(Pace measurements were worthless. The iPhone was in a pouch on the top of a backpack.)

Back to Day 22 | Back to the start

prep | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | coda | CHJ home