|

.\

.\

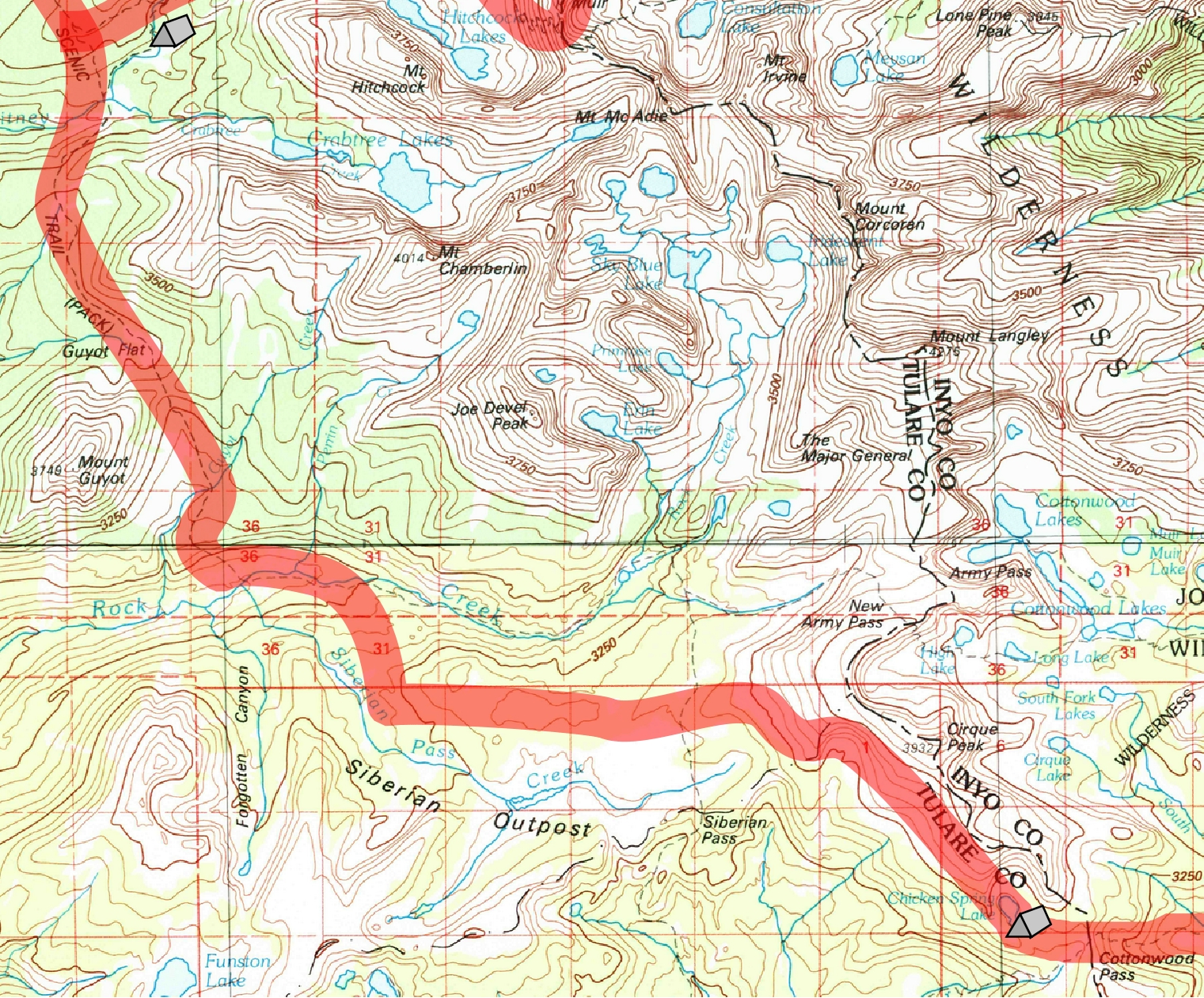

Now for a big exit. With the news that we could exit tomorrow at Horseshoe, we knew that we would want to get an early start for once and so made plans to try to get an early start. We realized that preparing daytime food the night before was a way to save time, so between that and getting Megan her breakfast early, we get off from our campsite before 9 am. Finally, a quick exit!

As is typical, passing through the camping area at Lower Crabtree Meadow elicits good humored attention as people notice the llamas and take pictures. But once we are past that area, the trail becomes empty. We take a last few views back up towards Mt Whitney as we climb out of the Whitney Creek/Crabtree drainage rather more steeply than I expected, the trail using a rather odd rubble slope that looks to be an old landslide. The trail exploits a couple of the lateral moraines of the Whitney glacier before swinging south towards Guyot Pass.

The terrain that greets us lacks the grandeur of the glacially sculpted peaks we just left, and the forest is a dry and fairly monotonous series of foxtail and lodgepole pines. The soil is loose granitic sand with only a few scattered plants. The few meadows we pass are a crispy yellow, offering little hint of any respite from the sere landscape. Mt. Guyot dominates our view to the south when we get glimpses through the trees; unlike the peaks we have seen before, it is a rather softened pyramid, sort of like what a pyramid made of butter might look like after a few hours out of a refrigerator on a warm day. The sharp edges of rock and the soft edges of vegetation that had been our companions through most of this trip are both absent.

The trail makes a steady low-grade ascent towards the pass, appearing to be aiming to make the pass without a switchback until forced at the last minute to tack back a little to climb over the summit. Trees and Mt. Guyot prevent much of a view, but as we proceed we can look south across the deep scar of Rock Creek to the highlands of the Siberian Outpost. That southern horizon is utterly unfamiliar, totally flat, a high plateau with some glacially exposed edges. The only peaks in view are to the west, across the Kern Canyon, in the Great Western Divide, a landscape we can only glimpse on occasion.

We now sweep downward, switchbacks defining the descent to the creek far below. I hope that the trail will contour more so that we hit the creek as high as possible. My maps here are not the most reliable, the trail having been diverted some time ago from what the old topo map on my phone shows. Although we avoid the very lowest point below the pass, we don't get to keep too much of our elevation gain. When we hit the creek, our first water since Crabtree, we cross and decide to have an early lunch (~11:30). Our excellent time bodes well for the day.

While we are there, I go through messages on the YB box and find a distressing piece of news: the Forest Service has decided that vehicles rescuing cars, hikers, and equestrians can only be on the road to Horseshoe from 9 am to noon. This means that we will only be leaving tomorrow if we can get to the trailhead early enough and if Greg can meet us. So I shoot out an email asking: will Greg be meeting us in that window? If he says yes, then we must go to Chicken Springs Lake, a long haul on the Pacific Crest Trail; if no, then we might as well travel up Rock Creek and enjoy a more relaxing afternoon.

While we sit on a rock by the creek, I see a figure coming down the trail and realize it is the Rock Creek ranger. Rob had said we might see him, so I hustle back to the trail to check and see. Not only is it the ranger from Rock Creek, it is the same fellow we met way back at McClure Meadow. He tells me that the only other people in the drainage are a couple that felt they couldn't leave over Trail Crest; everybody else has left. He is heading up to Crabtree, probably for company as much as anything, you'd think.

Earlier I had felt that we would make the call on heading to Chicken Springs Lake depending on the time we arrived at the trail junction. Now with the possibility that we might have to get there, I make sure to treat water so we will have enough. But when I use my UV wand, the red light flashes. My battery is dead. Of course finding the spares in the pannier is no easy task; the yellow bag with all the electrical stuff is buried and it takes some effort to fish it out. About then, that same horse group that had camped above us at Guitar and opposite us last night comes down the trail. One fellow offers that he has a couple of AA batteries handy that I can have, since he will be out of the wilderness before us. I ask where they are camping tonight.  One of the Rock Creek Lakes, he says. Hmm, I think, I don't know that they know that the window to leave Horseshoe is far tighter than we thought just a couple hours ago. If their information was based on what they got from their phones up on Whitney yesterday, they have no idea how things will go. Or, perhaps, their packer has a different plan that can work around any restrictions. Whatever, I figure that they have already made their decision (their stock train is, as usual, well behind them) and so don't bother to have a discussion about this.

One of the Rock Creek Lakes, he says. Hmm, I think, I don't know that they know that the window to leave Horseshoe is far tighter than we thought just a couple hours ago. If their information was based on what they got from their phones up on Whitney yesterday, they have no idea how things will go. Or, perhaps, their packer has a different plan that can work around any restrictions. Whatever, I figure that they have already made their decision (their stock train is, as usual, well behind them) and so don't bother to have a discussion about this.

We, on the other hand, know we might have a long day ahead of us and our excellent start has stalled out due to my troubles with the UV wand as well as a leisurely lunch and all this chit-chat. So as we head back on the trail I occasionally check the YB device for news. When we reach the trail junction where the trail along Rock Creek parts company with the Pacific Crest Trail, I check again and find an answer: yes, Greg will be there. OK, I answer, so will we. We turn right up the PCT.

Just why somebody thought this alignment a great idea is a mystery. Existing trails (such as those on the old topo map I have) carried a hiker down into Rock Creek drainage and stayed closer to the Sierran crest than this trek into the Siberian Outpost area. I guess PCT hikers were eager to reach Crabtree and so this cutoff seemed worthwhile. [There was originally a trail kind of near this alignment more than a century ago; whether that played a role or not, I do not know.] Whatever, the seven miles or so from here to Chicken Springs Lake is utterly dry. Climbing nearly 2000' from Rock Creek, this is our final challenge of the trip.

The trail winds around in odd ways, occasionally providing views down the Rock Creek drainage and across to the Great Western Divide. We rise in serpentine lurches separated by short flats. At long last we reach the summit area of the Outpost's northern edge. Although the southern edge is a bit higher, we are now on a large sandy flat. We get the odd look north and at one point can even glimpse Rock Creek Lake. A couple views of the upper Rock Creek canyon with its glacial landforms reminds us of the contrast with our present surroundings. On the other side, we sometimes can see pieces of the large sand-fringed meadows alongside Siberian Pass Creek, a look we haven't seen in meadows so far.

Those few views come between our march through this dry yet high elevation forest. Much of it is a continuation of the foxtail and lodgepole forest we encountered earlier, but in places the trees are simply unbelievably large. Foxtail pines approaching 100' tall (photo above/left) and incredibly stout lodgepole pines grow on this otherwise stark piece of land apparently untouched by glaciers. The surface is a deep layer of grus, sand derived from the simple disaggregation of granite that hasn't traveled anywhere, no doubt because of the gentle surface and the relatively low amounts of precipitation.

I check my iPhone map more often than usual; the day is getting late and it will be great to finish this slog. But the trail keeps heading east towards the mass of Cirque Peak, a peak lacking any hint of the landform for which it is named from our perspective. We finally reach a trail junction where we see, for the very first time, the well-known PCT trail sign superimposing a tree before a snow-capped mountain. After passing the Siberian Pass Trail (one I had traveled in 1988 doing seismology), our trail resumes climbing. Once it arrives at a suitable elevation, it turns right to contour high above the Siberian Outpost and most of the land beyond.

I check my iPhone map more often than usual; the day is getting late and it will be great to finish this slog. But the trail keeps heading east towards the mass of Cirque Peak, a peak lacking any hint of the landform for which it is named from our perspective. We finally reach a trail junction where we see, for the very first time, the well-known PCT trail sign superimposing a tree before a snow-capped mountain. After passing the Siberian Pass Trail (one I had traveled in 1988 doing seismology), our trail resumes climbing. Once it arrives at a suitable elevation, it turns right to contour high above the Siberian Outpost and most of the land beyond.

The perspective is mesmerizing. We first can better see the meadow along Siberian Outpost Creek, a narrow strip of green overwhelmed by a broad swath of sand with the distant Great Western Divide far away. As we rise more, our views now extend to the southern Sierra. The southern edge of the Siberian Outpost, near Siberian Pass, reveals a far more dissected region to the south and shows how the Siberian Outpost is such a curiosity, having evaded such erosion. Kern Peak rises out of a rolling green terrain beyond yet another large, sand-fringed meadow, Big Whitney Meadow (named in some early confusion on the location of Mt. Whitney). Farther left we catch views of the next significant Sierran peak, Mt. Olancha. A towering presence above its namesake town, from here it is a sort of monadanock, a lumpy peak rising through timberline and so distinguishing itself from the lesser, timber-clothed peaks comprising the Sierran crest to our south. As we move south, we increasingly seem to be on a platform dissociated from the streams and hills far below. The Pacific Crest Trail here truly is on the Pacific crest.

While all of this is very interesting to me, Megan and probably the llamas are intent on reaching our goal. We swing around one ridgeline to find a tiny cirque with a bit of water and some different vegetation, but this is not our goal. We trudge on, expecting each time the trail tops a small ridge and turns to the left that we will finally have reached our goal only to be disappointed. We pass out of the park, reentering the Inyo National Forest, the same forest we entered three weeks ago. Finally I consult my map and determine that a couple more ridges will pass before we reach the lake.

When we do finally turn and peer down to the lake, it is after 5 pm. Our earliest start is matched by one of our latest camps. Megan spies a good campsite from the trail as we wind down some switchbacks to the edge of a meadow below the lake. Spurning the trail to the right, we turn left. Megan and the llamas get stuck and I double back to take over llama wrangling; it takes bringing the llamas across the meadow to get to the site Megan found. We find her sitting there in a large rock-rimmed flat. This is to be our camp.

Despite the late hour, there are still chores. The llamas have suffered their longest day, and I head back to find a good piece of meadow for them. Along the east side of the meadow are a number of signs indicating that we should not walk through the meadow, etc.; such signs are absent on the other side. This meadow is quite lush and full of plants I haven't seen. Finding a part of the meadow I am sure is safe for the llamas concerns me. I finally settle on the west side where grasses like those we've used before are growing. Soon the llamas are tearing eagerly at these green shoots.

Another chore is filtering water for dinner and camp. I head up to the lake and find that there is no active outlet; the lake is currently a sink. A savvier hiker might have decided to then go to the creek in the meadow, but not I! The area near the outlet is pretty slimy, so I head up the lakeshore a bit and then pull up water from below the lake's surface and fill the gravity feed filter bag. As I head back I notice signs that this campsite is hugely popular. Beside the warning signs by the meadow, there are numerous sites with that pounded-down look of heavily used campsites. Any other summer Friday and this lake must be swamped with weekend campers. Not so tonight; with the fire closing the nearby trailhead, there is nobody to share our camp. Indeed, this is almost certainly the most isolated of all our camps. The nearest parties are the firefighters at Horseshoe Meadows.

As we are pulling water out of the filter, we notice the rate of flow is rapidly slowing. After getting only a few quarts, the flow is down to a drip. Evidently the clear water I pulled up was full of spores and the like that totally clogs our filter. We are able to get enough water for tonight but nothing more. Given that we will not eat another dinner, cleanup can be done with some paper towels. I put the last pot of water by the stove for the morning. The extra water we had from Rock Creek went undrunk and so will be available for our hike in the morning.

After we eat our freeze-dried meals, I go to bring the llamas back to camp. Grabbing Joe and Theo, I start across the meadow, but they both won't cross the small creek, so I finally head down to the trail crossing of the creek. Hearing the clatter of metal on rock, I turn back and find that Sarek has pulled up the meadow screw that he was tethered to. He follows a short distance behind us as we turn back uphill towards camp. Nothing so much as this revealed the social nature of these llamas. Once tethered again in camp, Megan starts to give the llamas the grain we have conserved this whole trip only to find that the llamas are very protective of "their" grain, regardless of whom Megan thinks she is feeding. So we have to separate the llamas a bit more before putting the grain in their Frisbee dishes.

While Megan retires to her tent, I decide to head out to Cottonwood Pass to see if I can get a picture of the fire that has caused us so much trouble; the possibility of catching a Perseid meteor above the fire is tempting. With the light fading and stars emerging, I use my flashlight in the areas not illuminated by the moon. A couple times I start to turn back but instead decide that I am so close that it would be silly not to get there. My persistence is rewarded as the trail descends to the pass. Walking a bit east, I see a glow down before me, so I set up my camera on the tripod and take several pictures. Although a nice meteor passes well to the south, none make it into my shots. Pleased, I turn back to camp; only tomorrow will I realize that the fire was actually farther to the left than I could see: the lights before me were from the fire fighting camp at Horseshoe Meadow.

I return to camp and lay out my sleeping gear. With the peak of the Perseids tonight, I intend to get some pictures, so my camera and tripod are at my side. Our last full day in the Sierra has been by some measures our hardest, covering 15 miles and rising 3000'. My goal is to rise earlier than usual at 5 am to get us heading out by 7 am. I figure that the trailhead is no more than five miles away, all downhill, so with our usual 2-2.5 mph speed we should make the roadend no later than 9:30 am. Tomorrow night should provide welcome rest, so any sleep deprivation tonight will be quickly forgotten.

Day 21. 7.2 camp to Rock Creek Jct, 7.7 mi Chicken Springs Lake; 10,450' Upper Crabtree, 10,300' Crabtree Crk, 10,700' saddle, 10,560' Guyot Flat, 10,930' Guyot Pass, 9510' Rock Creek, 11,000' Siberian Outpost, 11,350' park bdry, 11,440' saddle, 11,320' low point, 11,510' high point, 11,250' Chicken Springs Lake.

14.9 miles, 800' net elevation gain, 3050' total elevation gain

Total to this point: 196.5 miles traveled (206.1 for Megan), 38,190' total elevation gain (41,110' Megan).

prep | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | coda | CHJ home