|

Our last morning below 10,000' while on the trail isn't particularly special. Sleeping out worked out again, so at least I am not dealing with wet things as I pull together my gear. Food is brought back into camp and lined up, the morning foods pulled out and put on the tarp. Oatmeal is made, cereal eaten, gear packed. Sometime before 10 am Megan leads the llamas up a different path than the one we had descended on; we find the large camping area near the bearbox above us to be empty; the hikers who camped there last night are already gone, as are any others who joined them later.

Not too far up the trail we find the stock drift fence that separates the private-parties-only area from the part of the Bubbs Creek drainage where any group can graze. I don't notice any good spots for camping past that point; searching out our site last night was well worth the trouble.

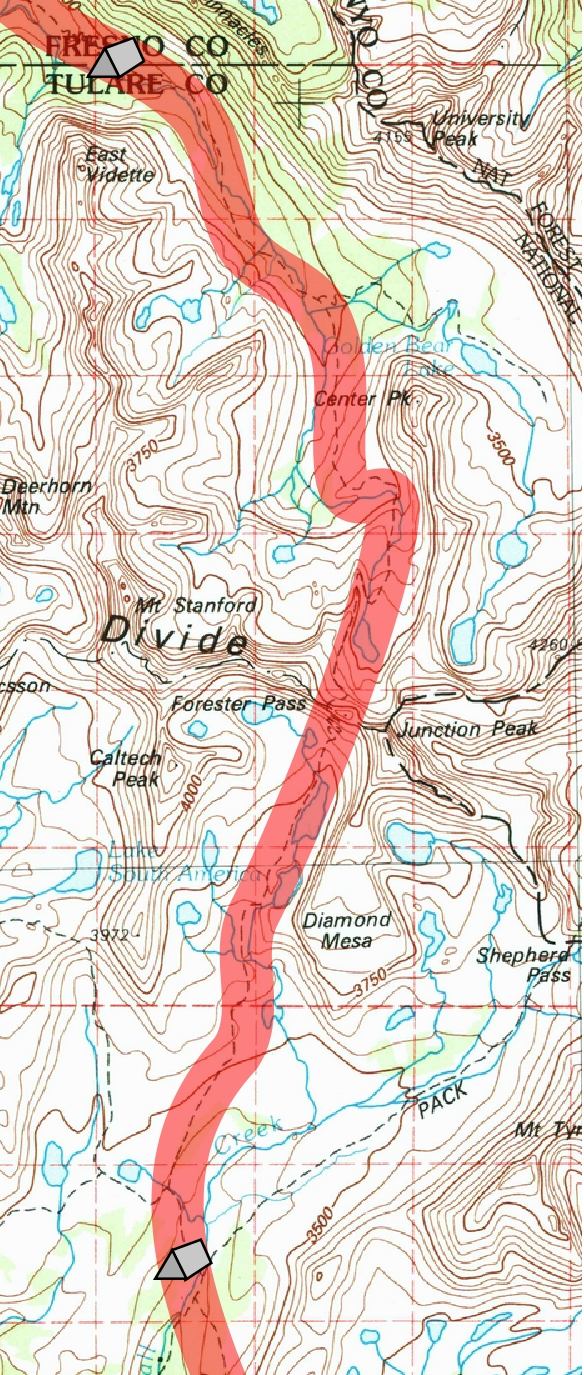

For awhile the trail closely follows Bubbs Creek, Center Peak rising up rather dramatically directly up the canyon. As we advance on that peak, though, the valley slowly bends to the right, our trail gradually heading more directly south. The wide mouth of Center Basin grows to the left; when we are basically under it, the trail bids farewell to Bubbs Creek and starts climbing up the east wall of the canyon. Somewhere near the top of this steeper stretch was the old trail into Center Basin--the old Muir Trail, actually, and a trail I had hiked many years before. Just as happened near Rae Lakes, we begin to hike a piece of trail I had missed in my older travels, despite the fact that both then and now I was traveling from Vidette Meadow to Crabtree Meadow.

Somewhere in here Megan has noticed me licking my chapped lips. "Stop it!" she scolds, "Every time I look back you are licking your lips, but you'll only make it worse." Add chapstick to the list of medical stuff we don't have but could use, along with tincture of benzoin and whatever stuff will prevent cracks in thumbs.

We meet a couple coming down from this area; the young man says that they had been trying to cross Forester, but he twice got a fierce bout of shivers and sickness that took hours to subside, so they are retreating back to exit at Kearsarge Pass. They had apparently camped quite far up the trail. I guess they felt it was altitude sickness, but the description of his condition sounds a lot more like a combination of some more pedestrian illness with some dehydration to me. I am sure they were disappointed; it underscores for us that the pass isn't a trivial one.

I have been worried about this coming stretch of trail for a long time. Forester Pass is more than 3000' above our camp last night, and after three straight days of climbing passes, this seems like it could be the worst. The trail, though, is exceptionally well graded, climbing up the east wall of Bubbs Creek's valley rather than plugging along the creek before hurtling up some switchbacks at the head of the canyon. Megan wonders where the pass is on the ridgeline in front of us, and I offer that I am not sure. I haven't checked the map, but I am inclined to believe a gentle saddle in the divide ahead of us must be its home. Yet when the trail turns hard to our left, rising into a small lake basin almost due south of Center Peak, I wonder if the trail maybe makes a climb into a sharper saddle next to jagged Junction Peak.

We turn back south and pass a couple of lakes. I recall from my guidebook that the last real campsite is at a lake near 12,300', and I wonder if we have passed it. We stop above a couple of the lakes for a moment and look for the trail up to the pass. We both fail to see it ahead of us, and it is then I notice that the trail makes a U-turn just a few feet in front of us: the trail doubles back to the south, climbing a rock face to get on the gentle ramp I had spotted from much farther below. Once we see the rockwork we notice some people on the trail. Reassured we are not about to have to climb the rock glacier below Junction Peak, we start forward.

As we take the turn back to the right, we see some folks resting at the outlet of this highest lake, the one I had been waiting to see. Junction Peak rises as a symmetrical triangle from above the lake, the deep gash on its east side that had impressed me long ago in crossing on Junction Pass not very visible from this angle. Forester Pass is a saddle high above us and more to the right. First, though, we head back south on this large switchback to gain the gentler approach to the pass. As often happens, we are stopped to chat a bit about the llamas before continuing on up.

Where the trail swings back north, we get a great view back down the Bubbs Creek drainage. Center Peak is just above the Sierran crest, but University Peak farther north, which is on the crest, is now the most prominent landmark. Far off in the distance, peaks are rising up above the walls of Bubbs Creek canyon. The farthest are back in the Palisades Group, near where we camped four days ago.

We now turn back south, and while this is a gentler approach to the pass, we still follow shallow switchbacks as we rise up the mountainside. Mt. Stanford rises as a series of ruined turrets from the debris apron at its base to our right, while the triangle of Junction Peak dominates the view to the left. The trail actually flattens out as we abandon our ridgeline to head to the start of the final switchbacks beneath the pass, so this nearly flat stretch is a relief for me. We can see figures at the pass now watching our approach as we begin the final climb up. As we hit the last switchback, Megan asks if I want to be above to record this highest ascent of the llamas on the trip, so I cut the switchback (after asking permission from the ranger perched at the summit) and record Megan and the llamas reaching the top. It is a quarter past 1 pm as we find the gap in the rock wall representing the pass. I move up off the trail to chat a bit with the ranger while Megan and the llamas stop a bit past the sign marking the summit. The sign claims we are at 13,200'; our guidebook claims 13,100', the internet tends to claim an official elevation of 13,153' while the truly official Geographic Names Information System claims 13,117', which agrees pretty well with my read of 13,120' off of the last properly surveyed topographic map of the area. [The topographic maps are the source for nearly all the elevations I've included in this diary].

I ask the ranger if he is the Tyndall ranger, and he responds that we have, in fact, previously met. He is the fellow we saw only a few days ago at the LeConte ranger Station. He and the Tyndall ranger decided to swap stations for a bit to get a little variety in their lives, so he hiked out over Bishop Pass and then hiked in over Shepherd Pass while we were walking more directly this way. I ask about grazing up ahead, as usual, and he says there is good feed down near his station, a mile off the Muir Trail. He says that another good spot are the frog ponds, which I am not familiar with but that I soon locate in my guidebook. I ask about Crabtree Meadow, and he gets on the radio to check with that ranger, who in turn says there is a good area at Upper Crabtree Meadow. That is good to hear. Megan is making gestures indicating she's not sure she's in a good spot, so I ask the ranger if she is OK with the llamas where she is, and he thinks it OK, so I indicate to Megan that we are good where we are. After taking pictures I pull out my lunch and start to eat. Our perch is so high that we can now look over the Sierran crest, seeing parts of the Inyo Mountains and other ranges off in the distance to the northeast.

Megan is still unhappy and so I finally go over to sit with her. It is only then that I realize part of her distress: I had thought she and the llamas were off the trail on a flat just beyond where it heads down. Instead they are directly on the trail; the gap near the trail sign is in fact a vertical cliff that some of the other hikers have been playing around with in taking pictures. Megan is unhappy to have been abandoned, as she was the authority on llamas with the hikers around her while I was talking with the ranger. For now, nobody is going by, so we finish eating our food. This summit is the narrowest of all and we will want to get going to be out of the way. We have been asking passing hikers whether there are any stock parties heading this way for some time out of fear we'd have to turn around with the llamas; fortunately none have been noticed by anybody.

A group now arrives that needs to get past us; they have to scramble around on the rocks to avoid the llamas; a group that has shared the summit is about to head down. It is decided that we will head down the sharp and steep switchbacks first. As I take some photos, I see that Joe, once again, pauses to examine a switchback while the other llamas and Megan are pushing forward (at right). I holler for Megan to stop and hurry down to once again trip the panic release and guide Joe down the trail rather than risking him jumping off the switchback. (We later hear that packers will often loose herd their stock down this section of trail rather than risk a misadventure like this).

A group now arrives that needs to get past us; they have to scramble around on the rocks to avoid the llamas; a group that has shared the summit is about to head down. It is decided that we will head down the sharp and steep switchbacks first. As I take some photos, I see that Joe, once again, pauses to examine a switchback while the other llamas and Megan are pushing forward (at right). I holler for Megan to stop and hurry down to once again trip the panic release and guide Joe down the trail rather than risking him jumping off the switchback. (We later hear that packers will often loose herd their stock down this section of trail rather than risk a misadventure like this).

After the first few tight switchbacks, the trail cuts right under the spot on the summit where the sign is and then continues its descent on a grade blasted into the rock wall. It is this southern exposure that caused all the trouble in building the pass some 80 years ago, and it isn't the best stretch of trail for acrophobes. But the views to the south are wonderful. Unlike any other pass, we are looking straight down the main stem river draining the area: the Kern drains due south. The closest equivalent view we've had was from the outlet of Evolution Lake, where we could look pretty far west along the South Fork of the San Joaquin. The Kaweah Peaks area holds down the right side of the southern skyline; a little left of that is part of the southern end of the Great Western Divide southeast of Mineral King. The trench holding the Kern angles a bit to the left, hiding behind a nearer arm of Diamond Mesa; the forested flats of the Chagoopa Plateau equivalents are prominent in our view, suggesting an older landscape with less relief.

As the trail finally maneuvers past the last blasted piece of rockwall, we get a view of Caltech Peak to our right, which we will pass below for quite awhile. As an alum of Caltech, I'm sorely tempted to figure out a way to climb the peak, as it looks to be a straightforward class 2 climb from where we are. But any camping up here would be quite exposed, so I don't bother to bring it up with Megan. We pause a bit to allow some of the hikers who have been close behind to get ahead of us far enough that we won't hear their chatter. All that remains for today is a long descent toward where the trail crosses Tyndall Creek before climbing towards the Bighorn Plateau, a crossing where there are supposed to be campsites.

The upper Kern is a stranger tapestry of bare rock, sandy flats, and grassy meadows than any we have seen to this point. The Kern is a drier part of the Sierra, and so some areas that might be awash in plants elsewhere are only thinly covered with meadow grasses. Streams this high have not cut into the glacial debris left from a few thousand years past; instead they seem casually draped over low rolling mounds and gentle ridges of bouldery moraine, their anastomosing paths creating a curious fabric to the landscape. Wetter areas are green with grasses and sedges; these are surrounded by blond swaths of dried out grasses and other, more drought tolerant plants.

Initially we are cradled between Caltech Peak and the walls of Diamond Mesa, but as we proceed we gain more of a view to our left. A wonderfully corregated ridgeline west of Mt. Tyndall comes into view, and then the peak itself, presenting the side first climbed by Clarence King and Dick Cotter in the 1860s. Mt Williamson shows up to the left of Tyndall. To the right of the ridgeline, the helmet of Mt. Whitney appears in a low notch. As we descend, we enter the upper edge of the foxtail forest. There is supposed to be a camp in one of the first patches we encounter, but water isn't obvious and we push on. Whitney falls out of view, but the broad swale accommodating Shepherd Pass comes fully into view.

The trail finally bends down to near Tyndall Creek once more, just above a spot where it starts to descend a bit more quickly to the west. There are numerous campsites in the trees here, but not a lot of grass. There are already some folks camped at some of the sites, though none are near the bearbox back near the trail. We scout around and settle on one of the lowest sites in the area, hoping to be able to graze nearby. Water is a pain--we have to crash through willows to get to the main stream. It turns out too that we are in view of the trail on the far side of the creek, and there are a few camps there too. Our streak of isolated campsites is at an end.

As we are settling in to camp, the ranger drops on by. He seems a little concerned about where we are grazing the llamas, and we consult the grazing map I have. It isn't entirely clear which of the several grazing zones we are in--they sort of come together near here--but in the end he seems satisfied that we are OK where we are. He will head off tomorrow on a big backcountry swing through the upper Kern region; I am sure he will enjoy it.

Dinner tonight is a couple of my burritos again for me along with some of the corn. Megan, hungry after her freeze-dried Mexican dish fails to live up to expectations, wipes out most of the corn. We hear from Greg that we can come out a day early, though he won't be there until late afternoon; he advises us to grab one of the livestock campsites when we get to Horseshoe Meadows. Megan and I are kind of non-plussed at this, as it means we won't really get back and started on our return journey until the 14th; maybe it would be better to just show up early on the 14th than to come out and camp one more night by the truck. Well, we tell Greg we will be there as early as we can on the 13th in case thing work out where he might arrive earlier.

So our 23 day hike is now a 22 day hike. It seems criminal to cut it back a day after all it took to get this going, but there you have it. Camping as high as we are tonight, it seems likely we'll get cold, so I am back in my tent.

We go to bed confident now in the remainder of our trip. Two nights at Crabtree allow Megan to climb Whitney, then we dash to get close to Horseshoe Meadows so we can be picked up as early as possible on the 13th. Too bad all of our certainty will be crushed in the morning.

Day 18. 6.9 mi camp to Forester Pass, 5.0 Tyndall Creek camp; 9870' Upper Vidette Meadow, 13,120' Forester Pass, 10,920' Tyndall Creek camp.

11.9 miles, 1050' net elevation gain, 3250' total elevation gain

Total to this point: 166.6 miles traveled, 32,740' total elevation gain.

prep | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | coda | CHJ home